Jayary Newsletter # 55

The City, the Village and the Forest

The history of civilization is mostly the history of cities and the countryside whose surplus feeds the urban monster. Cities rule our cosmopolitan dreams. The countryside is flyover country. Here's an untested and most likely wrong theory of mine: in the age of financial capital, the state is increasingly being replaced by a network of cities whose denizens hop from airport to airport sipping martinis in first class.

The flip side of the urban romance is the myth of the noble villager, the hard working, straight talking, simple living laborer whose sweat fills our bowls. That rugged farmer is the star of the Gandhian Ram Rajya and the American pastoral.

Do you see something missing in this pretty picture? Where are the trees? Where's the forest? All the wilderness has been squeezed between the empire of metal and the empire of grass.

The Jaya is an interesting antidote to this urban-rural civilization. There's almost no mention of village life in it; when the heroes leave the city, they enter the forest. The great hermitages and their demonic stalkers seek refuge amongst the trees. Can we imagine a world without farms? Where forests disclose their secrets in return for our care?

Janamejaya asks the suta how the Pandavas fed themselves in the forest. It seems they subsisted on their daily deer hunt - which they ate only after offering to their retinue of Brahmins. How many deer did the forest hold? What forest can afford a ten thousand humans hunting black buck every day? It's better that Arjuna's arrows rain upon his enemies than on the shrinking fauna.

The Steadfast Man

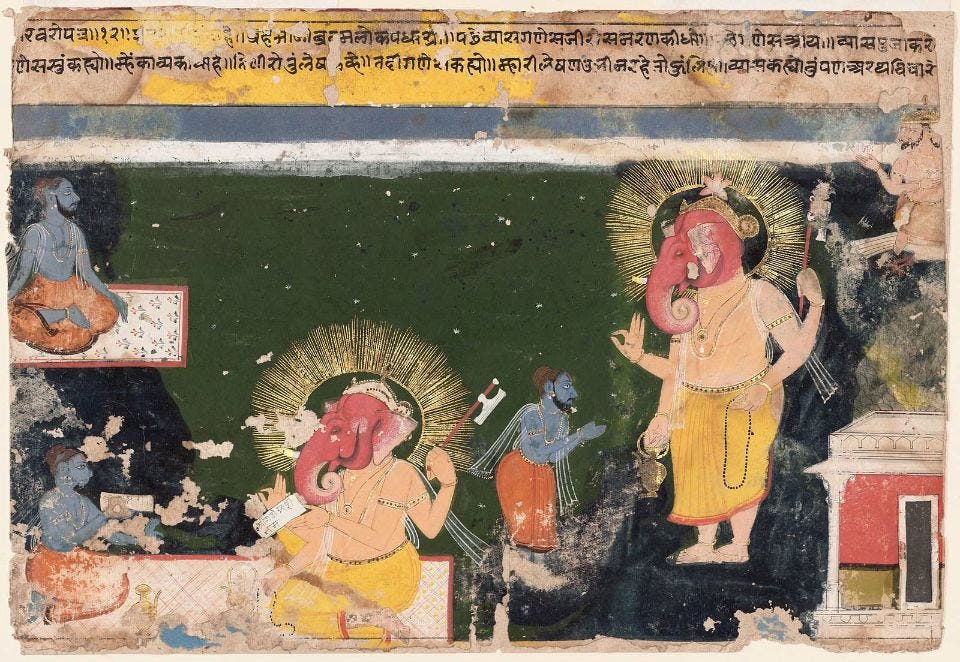

Yudhisthira follows the Dharma even in exile. When Krishna visits him in the forest and turns livid with anger at the condition of the deer-skin clad Pandavas, the blue skinned god promises to kill all the Kauravas and reinstall Dharmaraja as the legitimate king. Yudhisthira assents to Krishna's promise but extracts one in return: that the killing happen only after the thirteen years of exile have transpired. After all Yudhisthira has promised that he will remain in the forest for thirteen years.

I am of two minds about Yudhisthira's steadfastness. On the one hand, it's admirable to see a man whose word is his bond, a man who keeps his vows even upon the pain of death. It's the same fierceness that compelled the Sikhs to go their deaths when the Moghuls persecuted them. But how can we give so much authority to a word? Where does a promise get its power? Isn't it possible that the same allegiance to Dharma can turn fundamentalist and privilege the law over life, texts over people? Is Yudhisthira's rigidity the precursor of a future social order in which everyone is condemned to live and die in an oppressive hierarchy codified by law?

Meanwhile, Dhritarashtra is worried that these word-rich and wealth-poor nephews of his will descend upon his progeny and destroy them. Perhaps there's something to Yudhisthira's dharma; his promise-keeping attracts the best warriors to fight for him.

The Head and the Heart

If Yudhisthira is the head of the Pandavas, Arjuna is their heart. He's the bad boy of the clan, the sensitive warrior who also finds time to seduce apsaras and have fun on the side. He's the reason Draupadi married them all, and he's the reason Krishna makes the long trek from Dwaraka every so often. What would the Pandavas be without the two Krishna's?

(If I push the Family == Person analogy a little further, I might say that Bhima is their trunk, the twins the legs and adding a dollop of metaphysics, Draupadi their self. )

They need him even more than usual in their penurious state, since he's the only one of the five who can attract the gods and learn the secret of their divine weapons. That's why Yudhisthira sends Arjuna off to Shiva's abode in search of the Pasupata weapon. Fortunately, Arjuna doesn't complain about yet another quest: the third Pandava isn't the type who loves hanging out in the forest listening to discourses on metaphysics.

Meanwhile Bhima is stuck with Yudhisthira and Draupadi in the forest and can't stop complaining. "Why did you gamble away our fortune?"says Bhima, pointing an accusing finger at Yudhisthira, "and having done so, why do you have to keep your promise? Just say the word and I will kill all the Kauravas. Should have done that in the sabha itself, but Arjuna prevented me from crushing them." All thoughts in the Pandava family end with Arjuna.

Of course, we know what Yudhisthira says in response: "I can't lie, I can't break my promises, I can't step outside Dharma, blah blah blah." Terribly boring, but I also understand why his brothers obey his commands, for such unalloyed goodness is easy to trust.

The Antidepressant

Yudhisthira is understandably depressed. He lost his kingdom on account of the one rash act of his life - makes me think that it's better to indulge in small doses than to go on a wild bender - and while he enjoys the vacation from the daily pressure of governance, he's also losing support within his family. His beloved wife is intensely critical of their decision to stay in exile. Why wouldn't she, didn't the Kauravas inscribe hisfailings on her body?

Draupadi's lament is finding support with Bhima, who's itching for battle, and I have to wonder whether Yudhisthira has a sneaking support for the two. Since when did kings stick to principle? Principle be damned, but there's the worry about having the strength to fight their cousins in open warfare. How will they match the akshauhini's (remember what Stalin said about the Pope: "how many divisions has he got?") of well paid and pampered soldiers of the Kauravas?

Yudhisthira has no recourse but to send his other warrior brother to the heavens for special attention. It might be a good idea anyway to get Arjuna out of the forest before he can join Draupadi and Bhima in changing Dharmaraja's mind.

Without meaning to do so, Yudhisthira has collected worries like bees. No wonder the stress is getting to him.

A visiting rishi soothes his mind with a tale: "you thought your plight was terrible; well let me tell you the story of another king who lost even more and suffered even more than you have. You have four brothers; he had none. You have your wife. He lost his beloved. In comparison to Nala, you're fortunate indeed."

Thus starts the tale of Nala and Damayanti. One of the great love stories of all time folded within the Jaya as a great king's antidepressant.