Jayary Newsletter # 56

Nala and Damayanti

We will soon be hearing Nala's story, the tale of another great king like Yudhisthira who lost his love and his kingdom before regaining it all. I am never convinced that hearing about another person's misery makes mine any better and I bet kings are even less likely to be mollified by listening to a story of redemption.

Yudhisthira is an emperor who has lost his throne, and he's an emperor prone to reflection. But he's also an emperor and which emperor wants to be compared with other mortals even when that mortal is another king? Do you think Stalin would have been happy listening to the woes of Napoleon in 1815 after Hitler invaded the Soviet Union. I doubt it.

Still, we are obliged to suspend our disbelief and listen to Nala and Damayanti's journey. But before I start recounting it in my own words, here's another thought: why isn't it Damayanti and Nala's story? Why is it that Nala's suffering counts for more than Damayanti's? Or, coming back to our own heroes, why does Yudhisthira's fate inspire more tragic reflection than Draupadi's? After all, the eldest Pandava wasn't dragged from his chambers and assaulted.

There's inequality even in suffering, an inverted hierarchy that's a mirror image of the hierarchy of power. Just as the glory of a victorious king is greater than that of the merely successful writer or athlete, the fall of a king is lamented more than the bankrupt merchant or the abused wife. There's no escaping inequality, in good times and in bad times.

The Soulmate

Who among us hasn't dreamed of a soulmate, a companion of matching beauty and grace? Even better if in the process of finding that perfect partner, our bodies were upgraded to the perfection only attained by gods and movie stars. The Soulmate is one of three romances that we carry in our minds as we struggle through life, the other two being "The Buddha" i.e., becoming a human being who has either transformed himself into a god, or, forming a blend with the Soulmate, becomes intimate with the divine as lovers do; and "The Hero," i.e., the all conquering warrior to whom the entire world pays homage.

Of the three, The Soulmate is the most democratic. How many of us can hope to make the world submit before us? We are all Walter Mittys. How many of us can expect to have mystical, philosophical, poetic or scientific insight that renders the universe transparent? Both wisdom and power are rare and are acknowledged to be so. Love, on the other hand, seems within reach. Dating sites, friends and family, Tinder and Shaadi.com: a significant percentage of the modern economy is devoted to finding exactly the right person for us.

These apps in turn ride on a widespread fantasy: every Bollywood movie ever made suggests that every one of us has the capacity to woo that impossibly fair skinned girl carrying seven pitchers of water on her head while helping an old lady and breaking into song soon afterward.

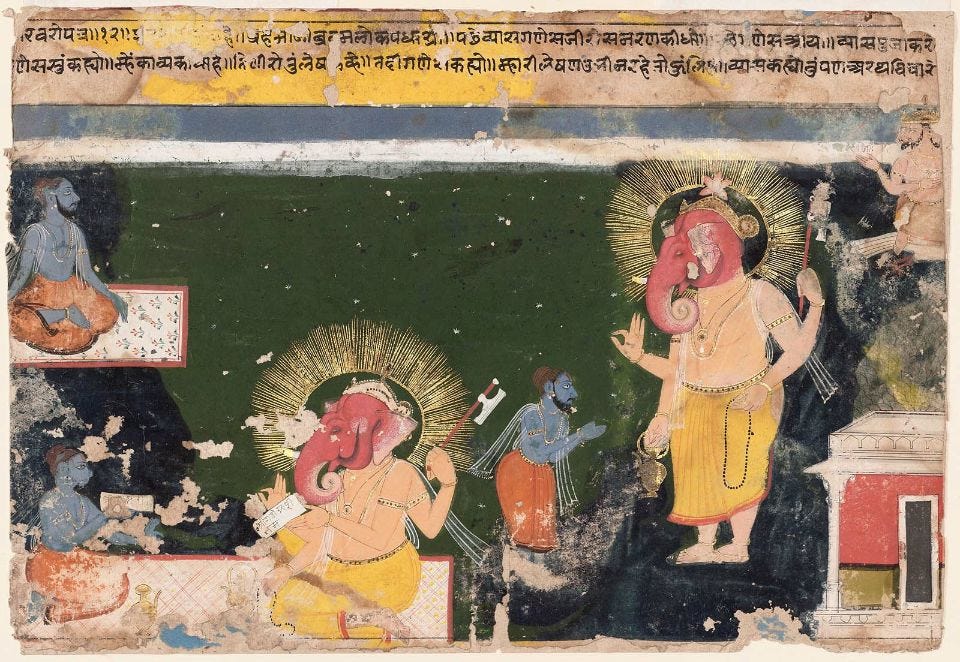

Paradoxically, the great lovers - imagine Romeo and Juliet or Rishi Kapoor and Dimple Kapadia in Bobby - are the humans most visibly different from us: better looking, better behaved, luckier in every sense of that word. They are both targets of aspiration and the most human manifestation of divine beauty, talent and power. Their divinity helps them find each other and fall in love instantaneously, as if fate had ordained their union. Their humanness forces a necessary element of suffering into the story, a trial or two to prove that they aren't gods. Nala and Damayanti are no exception to this rule.

Storytime

How two beautiful people met, fell in love, suffered, recovered their fortunes, suffered and recovered one more time and fell in love all over again.

It's the oldest story in the world and the story we want to tell about our own lives. It's the story of Nala and Damayanti. The story within a story has a teller and a listener; the visiting rishi Brhadvasa and the exiled king Yudhisthira. We are time-traveling eavesdroppers listening in to their conversation from an undisclosed vantage point; a perspective that's designed to enlighten us without disturbing the speaker and hearer. It reminds us that the Jaya is always a story to be heard, not a story to be read.

Imagine the two of them sitting under a giant tree in the late afternoon. The day's hunt is over. The deer have been slaughtered and served to the Pandavas and their cohorts after being blessed by Brahmins. The wooden vessels have been put away. Draupadi and Bhima are off to the side, one napping and the other fuming silently. We don't know what Nakula and Sahadeva are doing, but that's because we never know what they're doing. They're known to us only by their absence.

The king and his visitor have a few hours to confer before the evening deliberations start: should we attack the Kauravas? Why do you persist in honouring your gambling debts? Yudhisthira knows Draupadi will be asking difficult questions in the waning sunlight so he wants to dissolve his sorrows in story before heading back to face his family's interrogation.