Jayary Newsletter # 59

Error

We don't expect life to be full of surprises. When I pick up a bottle, it slips into my palm and stays there. We don't expect struggle with it, which we would have if it was made out of lead or stuck to the table with crazy glue. That normality is what makes life possible - imagine if every moment was beset with the fear of dragons - and it makes us all too vulnerable to the moment of surprise when it happens.

You drive to work on the same route every day and you're used to humming in tune with your favourite radio station and dreaming seventeen different methods of pushing your boss off a cliff, but then one day a car shifts lanes while you were in dream number 14 and before you know it you're in an ambulance on the way to the graveyard. All it takes is one mistake.

Nala makes that mistake after twelve years of patient stalking by Kala. He doesn't wash his feet after urinating and performs his evening rituals in an unclean state. That's all Kala needs to possess Nala, enter his mind and convince him to gamble his kingdom away to his brother Puskara. No one can convince Nala to stop his madness, not even Damayanti. Kala is the master of both fate and circumstance. All he needs is an opening to trap you into a circumstance beyond your control and soon fate takes over.

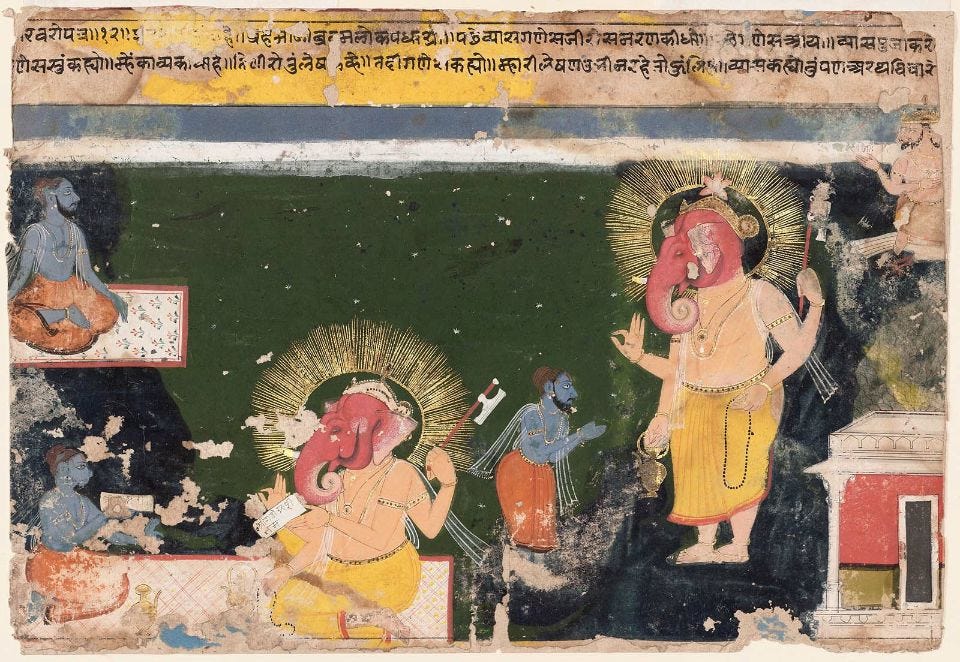

Angry Gods

Why was Kala so angry with Damayanti and Nala? Kala says he's upset with Damayanti for choosing a mortal over a divinity, but why would a divinity want a mortal in the first place? Even Kala has his limits though: he can't just kill or curse Nala. He has to wait for the right moment when a ritual error gives him an opening. There's a logic to the supernatural, as if heaven has unmoored itself from the earth but not so much that it doesn't partake of its essence. I find that situation fascinating: Nala's world lies between heaven - entirely divine - and our earth - entirely mortal. It's a world in which gods mix with humans and other beings often enough that their presence is unremarkable.

We can't believe in Nala's world; in fact, it's the definition of myth and fantasy. The only way to believe in Nala and Damayanti's story today is to turn it into a psychological narrative such as a dream or a science fiction narrative starring aliens visiting the planet. Both have their followers. Freudian psychology spawned an entire industry analysing dreams, myths and other psychic realities. The Freudian tide has ebbed now, but the "2001: A Space Odyssey" idea of aliens visiting the earth and turning us from beast to man is still very much alive.

I don't like either of these explanations; both are contrived. The sacred landscape visited by the gods feels ordinary to me, where by "ordinary" I mean that it's unremarkable, "the way things are." It's not experienced as half-real as dreams are; it's not experienced as a paranoid fantasy as alien invasions are. I can't imagine assimilating the lived reality of Nala and Damayanti into a psychic or extraterrestrial matrix.

Repetition

Nala's story is a lot like Yudhisthira's, or perhaps we should say it's the other way around. Yudhisthira has a jealous cousin. Nala has a jealous brother. Nala is challenged to a dice game. Yudhisthira is challenged to a dice game. Nala loses all his possessions. Yudhisthira loses all his possessions. It is almost the same story except for Nala being the victim of a God's wrath rather than a cousin's greed.

We can't get away with such obvious repetition anymore, certainly not in a written setting. The formulaic character of much ancient storytelling is lost upon us; it feels like needless duplication. That feeling is not restricted to stories alone; it's also present in our opposition to the memorization of multiplication tables and lists of random facts. Liberal education emphasizes principles over particulars.

Politicians can give the same speech in different campaign stops but no writer can tell a story in which the same misfortune strikes two different people. Unless they happened to be the same person in parallel universes or a story of twins separated at birth who get the same flavour of ice-cream at the same time every week.

Now there's a difference between oral and written literatures. Oral literatures thrive on repetition: it jogs our memories, serves as a semantic connect between episodes that might be heard days or months apart from each other and in general serves as an auditory frame that lends unity to the narrative enterprise.

So how do we tell Nala's story differently today? How can we transform the repetition into delight?

Risk

Risk, chance, uncertainty and contingency are at the heart of our world-straddling civilization. Credit drives every business in the world, from mom and pop stores to startups and giant corporations and every act of credit is also an act of risk. Will I default? Will I pay my credit card bill on time? Will I pay my credit card debt but only after it has accumulated interest? Our economy depends on avoiding the first, tolerating the second and welcoming the third. The stock market is a supercharged version of risk tolerance, except that decisions about risk and reward are now made at the speed of light.

I get the feeling that the Jaya hasn't mastered risk in the same way we have. Both dice games are rigged. Shakuni doesn't win because of his capacity to compute the probabilities better than Yudhisthira - otherwise how would he have won every single throw? In the modern gambling den such as the Vegas casino, the house mostly wins, but only in the long run. In fact, it's the local unpredictability of the throw that makes gambling so addictive. If you lost every single time, you would a) go broke soon or b) leave because it's the same negative result every single time. Gambling addiction is in direct proportion to the fluctuation of loss and victory and the dopamine rush that sends into our limbic cortex.

Why were Nala and Yudhisthira addicted to gambling then, especially when they were losing one throw after another? The Jaya explains the addictive behaviour through the means of spirit possession or some other extra-natural intervention. The idea that chance can lead to obsession isn't fully explored.