Jayary Newsletter # 69

Seconds

When you read a story for the second time, it throws up questions that didn't strike you the first time around. Nala and Damayanti's story is no different; it poses puzzles that don't reveal themselves as puzzles until their puzzledom is made obvious. Let's start with the pre-story. As we will see, nothing about Nala and Damayanti can be taken for granted, starting with its inception within the epic.

Q: Why was Nala and Damayanti's tale recited?

A: Because the sage Brihadasva took pity on Yudhisthira after notcing his depression.

Q: But why is Nala's story relevant to Yudhisthira?

A: Because the ruler of the Nishadas lost his kingdom to his brother after a game of dice, just like Yudhisthira.

Q: But didn't he gain it back after learning the art of gambling from Rituparna?

A: Yes he did.

Q: So why isn't Yudhisthira enrolling himself in an advanced course on probability? Why is he pining for his warrior brother Arjuna instead?

A: We don't know.

I am not convinced by the half-hearted claim in the Jaya that Nala's story is an antidote for Dharmaraja's woes. Having read it closely, Nala's story is not about Nala's loss at all. It's a love story, remember. The real plot of the story is Nala's rejection of Damayanti in the forest and the suffering they have to undergo before they're together once again. Incidentally, all of the detective work that reveals Nala's identity is instigated by Damayanti. It's her story more than it's his.

Is Brihadasva obliquely trying to send a message to Yudhisthira about his treatment of Draupadi? Is he asking her to listen to his wife? Nala and Damayanti might have had a more equal marriage than the Pandavas.

Katharaga

Is Nala and Damayanti's story a romance or a lesson in kingship lost and regained? Is it both? There's no definite answer; in fact, there can't be one for there's no single way of hearing the story. Indeed, in an oral telling, the suta can decide to emphasize the romance and downplay the power struggle. Or the opposite; it's the teller's choice.

When storytelling is more like singing a Hindustani or Carnatic raga and less like writing a linear account on paper, the suta has much more freedom to mould the current telling to suit his needs. There's no canonical text - only a template.

It's not just the supply side that's different when the story is a template; the listener is not the same as a reader either. An audience of rasika's, i.e., of people who have cultivated the same literary milieu as the suta brings much to the telling. They can signal their pleasure and displeasure; they can add embellishments of their own, or even better, at a time when memory was both more prodigious than it's today and the stories part of a common pool rather than the writer's intellectual property, a listener today could well be a teller tomorrow. Isn't that what happens to the Jaya itself: the suta Ugrashrava recites the tale just as he heard it recited by Vaisampayana at the end of the snake sacrifice, who heard it from Vyasa himself.

The oral form also explains the delight the epic takes (and it shares that delight with most ancient story cycles) in layering one story inside another like a Russian doll, especially the instructional story. Today, we use footnotes to mark an aside, but an aside makes sense only when there's a linear structure to the main narrative, as is the case in most written scholarship and even in fiction.

What if there's no main narrative: what if every story is one node in a network of stories? It's a commonplace idea in the internet era: who thinks of discrete pieces of content anymore? However, what's changed is that the internet is the internet oftext; it's not a throwback to oral traditions, but a mutation in the concept of writing.

All of this is to say that as I reread the story of Damayanti and Nala (perhaps in preparation for a retelling) I want to reread it not as an oral story within a story, but as a written story within a story. Our condition is the written condition, and it's in that condition that we have to explore new forms of narrative both for literary and philosophical purposes.

Playing with Fire

The oral word is like a puff of smoke released into the air from the speaker's mouth. But then again, where there's smoke there's fire right? Who is the fire?

Again and again, we hear the Jaya express the fire is Agni, that speech, knowledge and power need Agni as witness. How did humans get access to fire and what price did we have to pay for it?

It's a question that's been asked wherever questions are there for the asking and answered in as many ways, but there's a common thread to the answer: we never go unpunished. The Greek gods were cruel in the extreme: Prometheus is chained to a rock and has his liver eaten by an eagle for eternity.

The Jaya is arguably as cruel, except that here humans cut a deal with the divine. Agni demands the sacrifice of Khandava. In return we get a cleared forest on whose ashes Yudhisthira builds a great city.

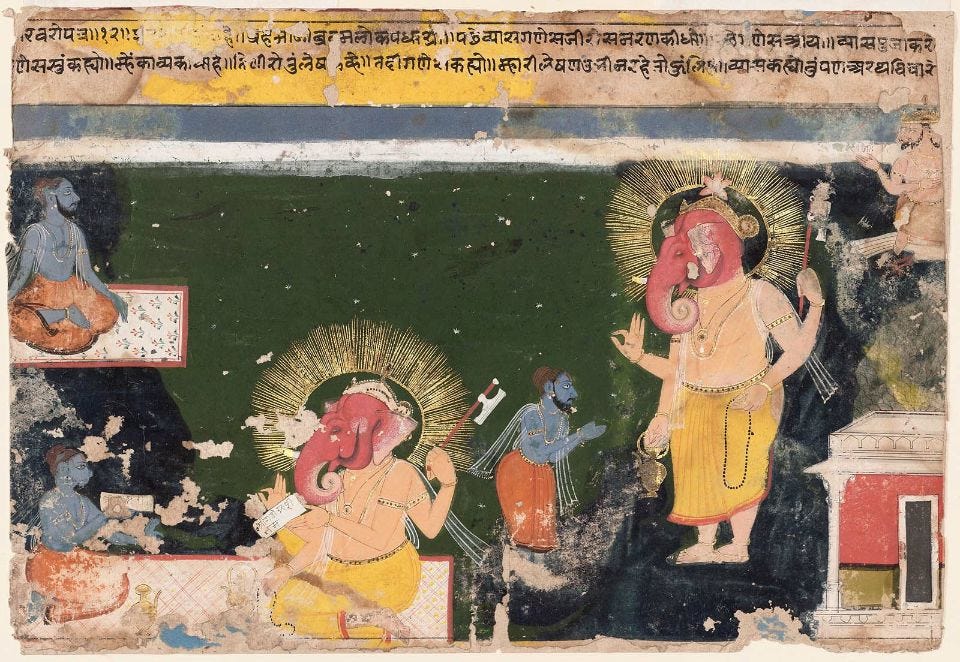

Therein lies the genesis of Nala and Damayanti's story. People and gods are still in close contact: they make deals, they sleep with each other, but you know, just like the relationship between India and the United States, even when we sleep with each other we know who's boss. Not as an absolute rule of course; some humans have an upper hand over some gods and some Indians have an upper hand over some Americans, but the balance of power is clear to everyone.

Sometimes you sell your goods to the wrong buyer. Some deals go sour. When that happens, feuds break out. These fights are often settled over the bodies of women. Damayanti. Draupadi. And countless others. Is Agni a witness to these sacrifices too?

The Object of Power

When Brihadasva arrives in the forest, Yudhisthira is moping. Why wouldn't he? He's lost his kingdom. His brother's aren't happy with his leadership and his wife is aflame with anger. Isn't that a king's lot? No wonder it's lonely at the top.

I am fascinated by the dual nature of power. On the one hand, it gives you the authority the control other people's lives. On the other, it makes it impossible to have truly intimate relationships. There's a surface reason for that distance: a king can't repose absolute trust anyone and they certainly can't repose trust in him, for to be a king is to betray everyone else for the purposes of statecraft.

But that's only the surface psychology of kingship. There's a deeper epistemological reason: to be an effective king, one has to see human affairs objectively, i.e., to see people as they are without any romantic illusions and to seem them as objects to be manipulated.

That objectivity imposes distance by its very nature. The puppet master can't become friends with his puppets. Isn't that the reason why the gods left the earth? As they discovered their responsibilities as sovereign, they needed a better vantage point to see the world objectively, to create - literally - the god's eye view of the world.

Of course, kings are people too and give in to their human desires. Both Yudhisthira and Nala gamble away their throne, but that's not the complete story. Nala and Damayanti's tragedy is also a consequence of the god's lingering desire to be on earth. It's not just the humans who are fallen; it's the gods as well. No wonder there's a movement to merge the gods into the one God who rules them all.