Jayary Newsletter # 73

The First Question

Who asked the first question?

We know who gave the first answer: it was Prajapati, who said "DA" in response to the devas, asuras and manavas worries.

Doesn't that mean the first question was asked by one of those three beings? Not so fast; I said Prajapati gave the first answer and it was "DA." That doesn't mean the first answer was given for the first time to the three anxious species.

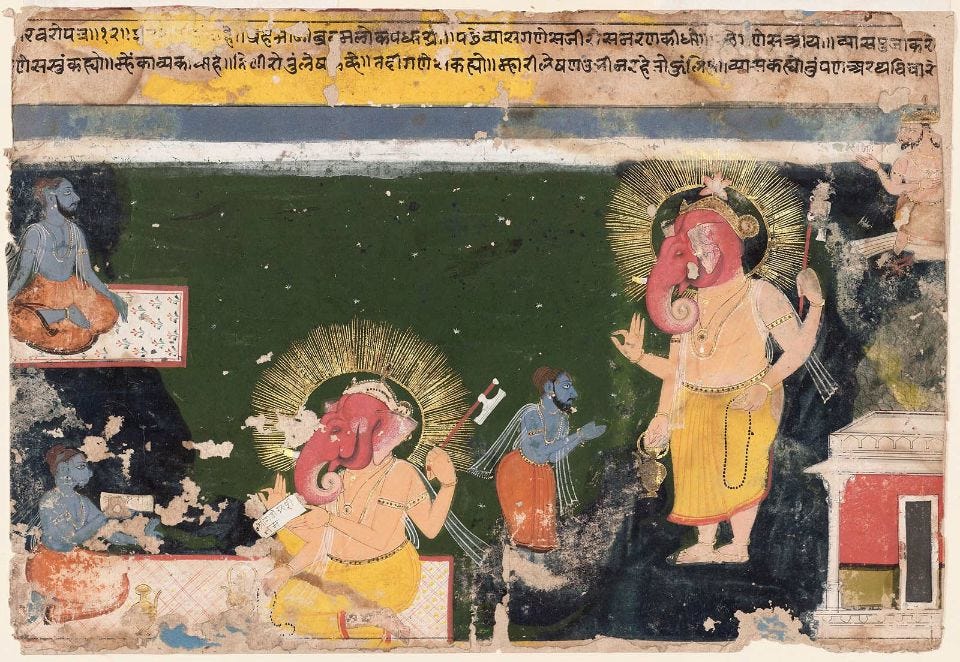

There's reason to believe that the first answer might have been given by Prajapati to himself. For at the beginning, when he was all alone, Prajapati said to himself, "I am all alone" and he gave himself a body. Wasn't that the first desire, the first question and the first answer? Because of which we have all been fated to be born, grow old and die.

Since we aren't Prajapati, we are always asking a question for the nth time. When Yudhisthira asks Narada about the importance of pilgrimages, Narada says:

"Let me tell you a story. Once upon a time, your ancestor Bhishma was performing puja at the banks of the Ganga. The rishi Pulastya was so pleased with Bhishma's efforts that he came up to the Kuru prince and said:

"I am pleased with your efforts. Ask me anything and I will answer."

The awestruck Bhishma said to the glowing rishi:

"Mahatma, tell me one just one thing and I will be happy: what is the purpose of pilgrimage? Why should we roam the earth offering our homage to the gods?"

"You see" said Narada to Yudhisthira, "this question has a past in your family."

Pilgrimage

What I like about Yudhisthira is that he's good at asking questions and seeking advice. He isn't like Duryodhana who rarely listens. We find Yudhisthira answering questions only under special circumstances: when he's tested by the Yaksa, when he's queried by Dharma, i.e., when he's answering questions as a seeker rather than a king.

So when Dharmaraja asks Narada "why should we go on pilgrimages?" I take his attitude seriously. He wants a genuine answer. So does Bhishma when he asks the same question of Pulastya.

Why should we go on pilgrimages?

It's a axial question, a question around which we can construct an entire universe of inquiry. I want to know Pulastya's answer to this axial question, but I don't want to read the answer until I have taken a few minutes to explore it myself.

Why should we go on pilgrimage? What is a pilgrimage?

Pilgrimage makes no sense in the liberal culture we inhabit. Religion is a private affair, at best a special relation between a worshipper and his deity and at worst lip service one performs at home before cutting down a forest and or launching yet another subprime loan. That liberal attitude voids the purpose of a pilgrimage even if you pay Gold Star Travels fifty lakh rupees to take you to all one thousand and eight holy places on earth.

Dharma is not private. It's not about psychology, even as it includes psychology. Dharma blankets the world. Pilgrimage is a special kind of karma, action that's also also knowledge, and knowledge that's reaffirmed in the act of doing so. The temples we visit are the coordinate marks of that knowledge.

Who said knowledge is in our head? It's there in the world, which is both inside and outside. Akam and puram as Tamilians would say. The pilgrim is a witness to the world. Let's see what Pulastya has to say about it.

Controlled Worship and Free Worship

I was surprised by Pulastya's answer to Bhishma's question about pilgrimages. Positively surprised. While there's a long list of pilgrimages in Pulastya's answer, his basic message is:

Pilgrimages are open to everyone, unlike yagnas that only the rich can afford.

Pilgrimages are even more efficacious than yagnas.

What's a yagna?

It's a sacrifice under prescribed conditions, a ritual in which everything from the amount of ghee to be poured on the sacrificial fire to the payment to the presiding brahmins is set in stone. Yagna is controlled action.

In contrast, a pilgrimage is free action, a movement in which the pilgrim is allowed to pay his respect to the gods in whichever way, as long as he transports himself from one holy site to another. Interestingly, the pilgrimage that Pulastya cites as one of great power is the one at Puskhara, the only place in India where Brahma is still worshipped.

I am wondering if there was a slow movement away from pilgrimage to natural sites of worship - marked by water or a tree or some other natural object - to worship within temples to the worship of texts. It's a movement away from the worship of divinity to the worship of a representation of divinity. Was that the cause of the gods leaving the earth or the result?

The tussle between controlled work and free work is not one that afflicts religion alone. Consider science: it costs a lot of money to run laboratory experiments, but it costs nothing to look at the stars. One of the dangers of light pollution is that it takes away the experience of nature from us ordinary folk. Only those who have access to space observatories can become astronomers today.

The Magical Forest

Pushkara is a magical forest. It seems that visiting it on a full moon night of Kartika is equal to spending a hundred years doing the agnihotra . A powerful pilgrimage if you're to ask me.

What makes it so powerful?

Did you notice that Pushkara is a forest? Pulastya says it's an extremely difficult place to reach and even more difficult to live. It's in this dense forest that Prajapati made his home and where he remains to this day, even as the forest has been replaced by desert.

Is it any surprise that the oldest of the gods, Prajapati Brahma, has almost vanished from the earth? Where would he live, now that the forests are almost gone? Perhaps in the Amazon or in Borneo, but even there we are cutting down virgin forests for palm oil. Can't imagine a worse trade-off.

I am only now beginning to understand the specific character of every sacrifice and every pilgrimage. Why visit this temple on that night? What's so special? We live within clock time and metered space and in doing so, we have forgotten the differences that are internal to time and space. Here and there we experience the pull of spatial and temporal difference; when we can't sleep because of jetlag or when we find ourselves weeping after looking at an old photograph of the house into which we were born. Those exceptions only make the rule: life is the same for us in Beijing and Bangalore and Boston.

What is like to inhabit the earth with special instructions for specific times of the year and specific places on the map?