Four ways of looking at technology:

J.J. Gibson figured out that objects around us hint at how we should use them--like how a handle suggests pulling. Donald Norman took this idea to the next level in design, arguing that things should be so straightforward to use, you don't need an instruction manual. Think about it: when you see a chair, you instantly know it's for sitting, right?

Now, enter David Chalmers with his concept of "technophilosophy," where we use technology to explore big philosophical questions. I am adding a twist to Chalmers' tale: design-philosophy, which is about looking at design not just as making things look cool or work well, but as a method to grasp philosophical problems and use artifacts as explorations of philosophical ideas.

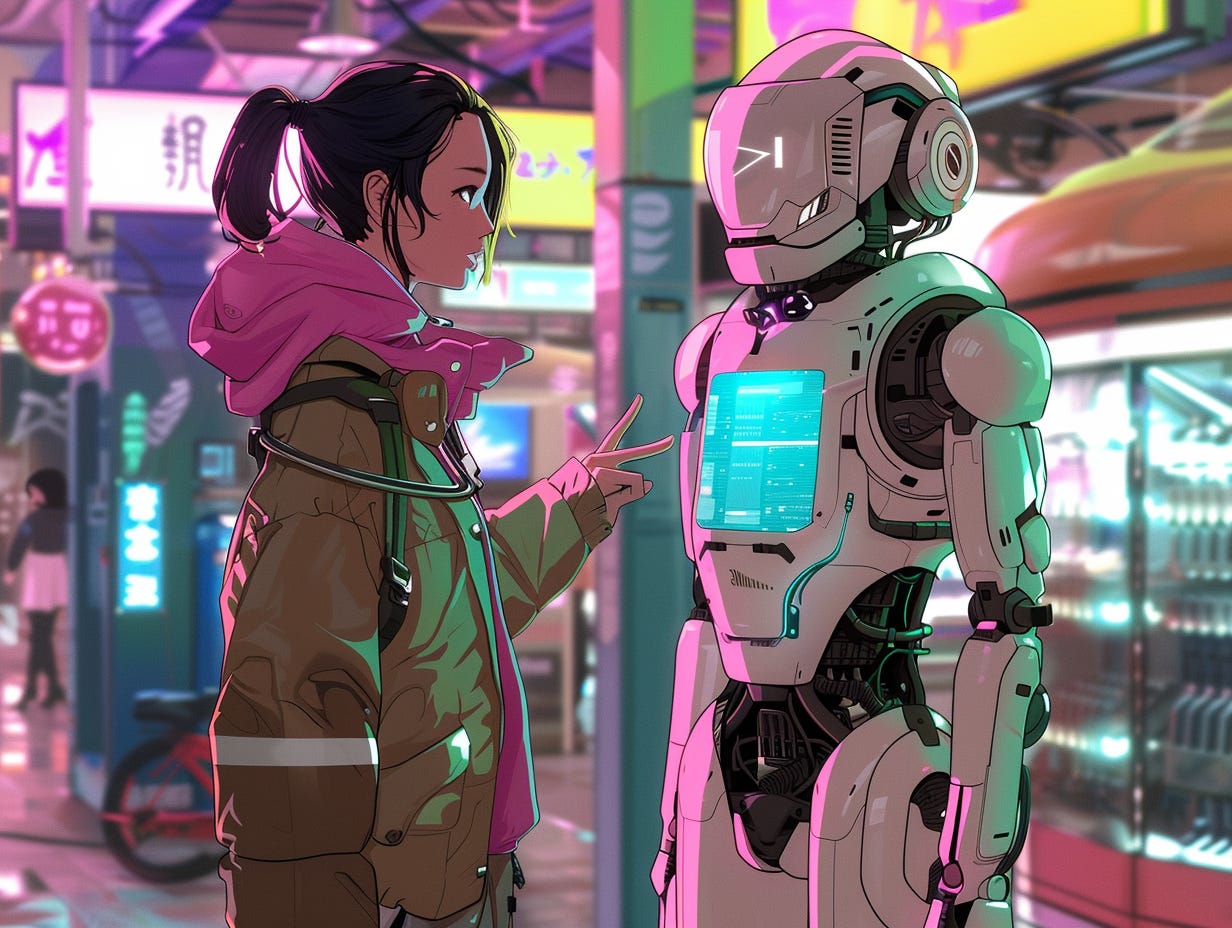

In short: as technology becomes a bigger part of our lives, it starts to shape our behavior and culture in new ways. We're talking about a future where AI might become as intuitive as using a smartphone, changing how we interact with the world around us.

All this and more in this week's newsletter.

Stones are made for throwing. Handles are made for pulling. These lessons don't need to be taught; they are 'directly perceived,' according to J.J Gibson, the heterodox perceptual scientist. J.J. Gibson was an influential theorist of perception from the mid-20th century, even though he was outside the mainstream of cognitive science thought. Gibson wrote several books. He was an unusual scientist in that his prominent publications weren't peer-reviewed journal articles; they were monographs, seminal books he wrote. Gibson had several ideas that have continued to come back into the mainstream and shape thought. And one of them, arguably his most significant, was this notion of affordances, which is just that our environment allows particular actions. A handle on a cup affords grasping, and a handle on a door affords pulling. Affordances connect the oldest tools we invented - some even before we became human - with tomorrow's spacecraft.

Donald Norman built upon Gibson's concepts, and brought them into the practice of Human Centered Design. Gibson's core idea was that the objects and environments around us inherently suggest the actions they support—they 'afford' certain possibilities. A chair affords sitting, a button affords pushing. Norman took this concept and applied it to the realm of design. He recognized that good design should make affordances immediately apparent to the user. An object's intended function should be self-evident, reducing the need for extensive instruction or complex interactions. Norman famously applied this principle in his seminal book, "The Design of Everyday Things." He analyzed how seemingly simple objects—doors, faucets, light switches—could be poorly designed in ways that cause frustration and confusion. His work highlighted the importance of designing objects that align seamlessly with human intuition and natural tendencies. Norman's approach has been instrumental in pushing design beyond aesthetic concerns and putting user needs and experiences at the absolute center.

Norman advocated a design approach that prioritizes human needs, suggesting that we should shape our objects, buildings, and systems to cater to humans rather than expecting individuals to adapt to the design of these entities. This perspective revolutionizes how we approach creation and innovation. Instead of merely considering aesthetics or functionality in isolation, Norman emphasizes the symbiotic relationship between artifacts and their users.

In a recent book, David Chalmers introduced an interesting term “technophilosophy” that is relevant to our concerns. Technophiiosophy is thinking about philosophical questions using technology as opposed to Philosophy of Technology, which is philosophical thinking about technology. AI has been a source of technophilosophy for a long time. While the philosophy of technology explores the impacts and meaning of technology on society, technophilosophy uses technology itself as a lens to investigate philosophical questions. AI, in this sense, becomes both a tool for discovery and the subject being analyzed. One way to read Norman is as ‘design-philosophy,’ - awkward term - addressing philosophical questions using design. Since design is essentially about how things relate to people’s needs, their flaws reveal flaws in our thinking about people. Instead of asking whether free speech is protected by the constitution, we can ask: are our apps designed to protect free speech? And what other problems arise because they protect free speech or fail to do so?

By putting humans at the core, designers can craft solutions that are not only functional but also intuitively relatable, enhancing overall user experience and satisfaction. Such an approach not only benefits the users but also makes the creations more sustainable and effective in the long run. After all, designs that resonate with human instincts and behaviors are less likely to become obsolete. It challenges designers to prioritize empathy and understanding, forging a stronger bond between humans and the designed environment. Good design amplifies human capabilities by using affordances to interface with technologies, and once that technology is widespread, new affordances emerge at a higher level of abstraction.

In our lifetimes, mobile computing became the computational medium that spread from hacker communities and a small set of office workers to everyone. That cultural shift has spawned a whole new universe of gestures and symbols and a social infrastructure around them. The true success of technology lies in its ability to evolve alongside human needs, seamlessly augmenting our existing capabilities. This transformation is evident in the rise of smartphones and the vast ecosystem they support. We swipe, pinch, and tap with an inherent familiarity – these once-obscure gestures now feel as natural as the flick of a wrist. This symbiotic relationship between human and machine drives the birth of novel behaviors and rituals. The way we socialize, navigate, and express ourselves has been forever altered. Design, in this context, becomes a catalyst for cultural evolution, shaping not just the tools we use, but how we understand ourselves within an increasingly technological world.

How will the design of AI drive cultural evolution? The most common AI interface - chat - doesn’t have enough affordances yet. It is deceptively simple: you ask questions, and it responds, but there's no background of common knowledge or immersion in the same place and time. Want a story about a child who grows wings and starts living in a treehouse in the backyard? You got it. Conversations between humans assume their joint embodiment, that they are in front of each other, can observe each other's gestures, and point to objects in the background. They can dip into reserves of common knowledge - say political events - and also signal things one participant knows, but the other doesn't. In contrast, when talking to ChatGPT, there is no representation of the conceptual territory being traversed or gestures that serve as signposts.

The limitations of current chat-based AI highlight a crucial design challenge: the creation of a shared context for richer interaction. The nuanced dynamics of human conversation are intrinsically tied to embodiment – a common physical space, gestures, and a wealth of unspoken cues that guide our understanding. In its current form, chat AI lacks this multi-sensory dimension, creating a sense of disconnection. Future AI interfaces must strive to bridge this gap, perhaps through visual representations of shared knowledge, the ability to reference objects or environments within a conversation, or even virtual gestures that convey intent. Imagine an AI companion that can understand the way you point at a map or nod your head in confusion, adding deeper layers of meaning beyond the confines of mere text.

Just as the mastery of horses or the operation of cars requires a nuanced understanding of their capabilities and limitations, so does the effective use of AI demand a comprehension of its potential and boundaries. The transformation brought about by AI in society could soon be akin to the revolution of horseback riding or the advent of automobiles, but with a complexity that could surpass both. AI, much like these earlier innovations, will reshape the way we live, work, and interact. Integrating AI into our daily lives necessitates an infrastructure not just of technology but also infrastructures of common knowledge and a common stock of navigational gestures and conceptual infrastructure. It also needs a mythology, a way of being cool (even if for your fellow nerds and no one else). James Dean made cars cool. Can Hollywood tell a similar story for AI?