We live in a world in the midst of profound transition. The end of history’s faith in liberal democracy has crumbled, replaced by an illiberal global capitalism, sinking “liberalism as culture” alongside “liberalism as power.” With the collapse of the liberal Leviathan, a new possibility emerges: Bhumics, conceived as a planetary framework superseding politics and economics.

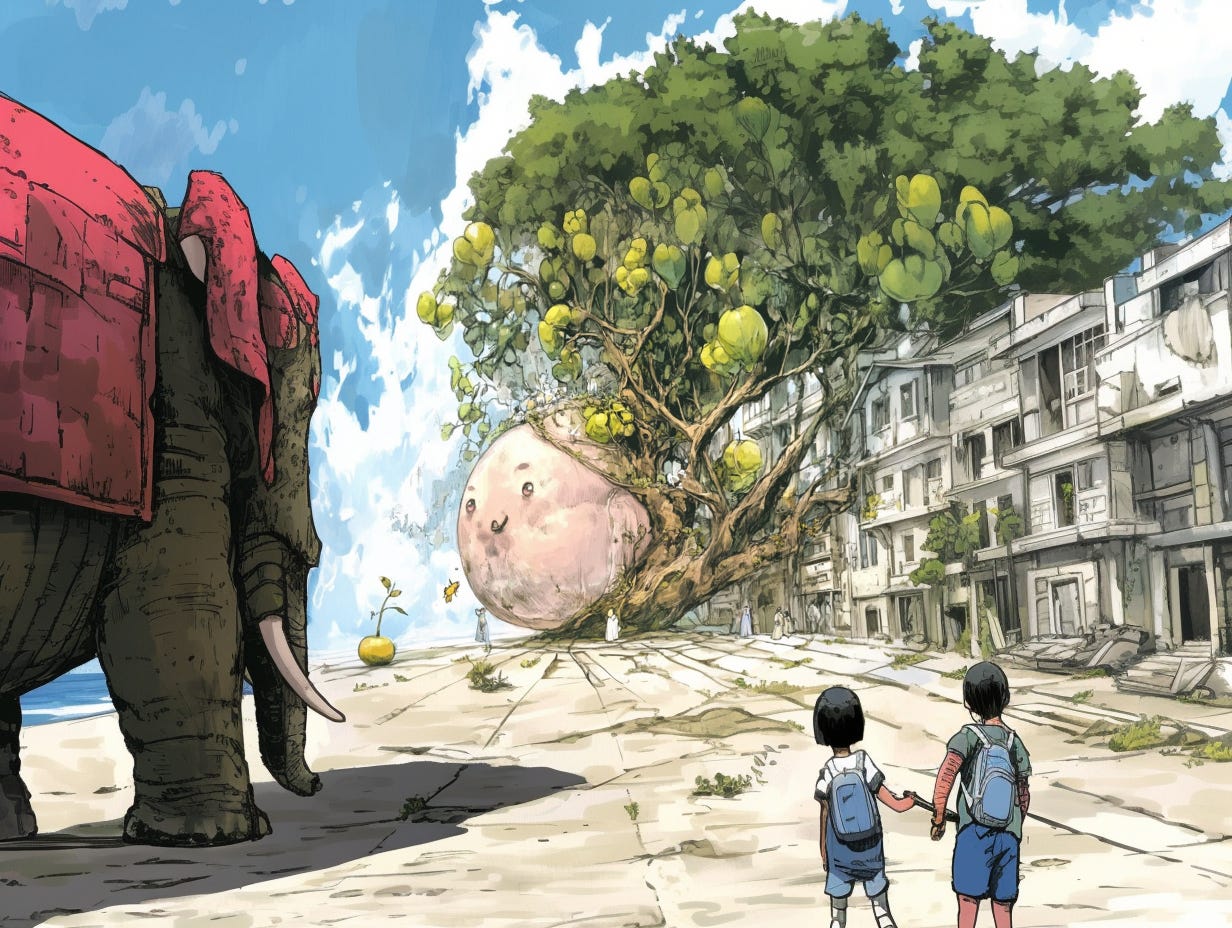

Drawing on Gramsci’s concept of an interregnum—a time when the old order is dying but the new one remains unborn—I want to explore the shift from hope to fear as the ruling emotion of our age. The “time of monsters” is upon us, when new hegemonies are yet to arise. I believe the next monster will be planetary in scale, shaped by climate crises, shifting demographics, etc.

Scattered thoughts follow…hoping to make them coherent by the end of this year.

Questions for future reflection

1. How can we embrace a planetary politics without slipping into utopian idealism?

2. In what ways might a shift from hope to fear reshape our collective imagination?

3. How can speculation guide us during this uncertain interregnum?

I've been uncharacteristically quiet - the last time I wrote here was in August, many a month ago. I know what occasioned the silence - the ongoing genocide drew me into such fury and despair that I didn't have any reasonable thoughts worth sharing. But a ceasefire has been signed just this past week, and has just become effective as I write this piece - we might be at the verge of post-genocide politics. Still guaranteed to be apartheidist, but....Trump's coming to power is triggering a collapse of many ideas and ideals my head had set aside a long time ago, but my heart was still holding on to.

What ideas? What ideals?

Affectology

Until recently, liberal democracy seemed to dominate global politics. Today, that Leviathan is gone and what we are left with is a global capitalist system with varying degrees of illiberalism in charge. I am no fan of liberalism as a system of power, and I've not been for a long time, but in saying so, I am making a political statement. I am a cultural liberal, a man who enjoys living in liberal communities, conversing in liberal circles, and a member of liberal nations. Liberalism as culture has always been an ideal. It feels like liberal culture is no longer an ideal and more controversially, the passing of that ideal is liberating.

Why?

Because the only transformative culture or transformative politics worth having today is planetary politics and planetary culture, a Bhumics replacing politics and economics and many other -ics.

Bhumi: Earth in many South Asian languages.

As long as the liberal Leviathan had me in its clutches, it was impossible to invest wholeheartedly in planetary culture and politics, like imagining democracy when an enlightened king is in charge. Can be done, but no one's buying it. With Trump's second ascension, and we really don't know what the next four years are going to be like, it is possible to realistically imagine regimes of a whole another order from the ones that are extant today. Today is the day when I can say Bhumics should become the ruling principle of cultural and political transformation.

It is a new beginning, and I hope to be able to write about it at length. I am not saying planetary politics and planetary culture will become the norm in my lifetime, or even in my daughter’s lifetime, but it’s now possible to think it as an actuality.

Bhumics is an aesthetic, a mood as much as an ideology. As an aesthetic, it should evoke new emotions. Which ones? I don’t have a good answer but I am hoping to discover a candidate emotion by juxtaposing hope, a liberal emotion, and fear, an illiberal emotion.

What affectologies (contrast with: ideologies) are implicated in the two?

If globalization under American hegemony started with Clinton's presidency and continued through Obama's presidency, you could say that hope was the ruling emotion of those 25 years. We are now close to a decade into the emergence of fear as the reigning emotion - and not only in reactionary circles with their anti-immigrant rhetoric, but also in liberal circles with climate anxiety. What does it mean for hope to be supplanted by fear as that dominant emotion?

What kind of affectology explains the shift?

I don't want to assume that Bhumics has to be touchy-feely, earthy-crunchy. In fact, we may want to have a Machiavellian approach to planetary politics as much as a Utopian. It's the shift from the national and the global to the planetary that's the important shift not the specific frame in which the planet has to be thought.

Monsterology

In a time not unlike ours, Antonio Gramsci wrote these words from his prison cell (published in his Prison Notebooks):

The old world is dying and the new world struggles to be born. Now is the time of monsters.

That old world didn't die completely, but its center shifted from Europe to America. A century later, rumors of its second death continue to proliferate, but we don't know if they are greatly exaggerated. What exactly is dying? Is it:

1. The neoliberal world, whose death was announced during Trump’s coronation? -- seems certain; topple Milton Friedman statues wherever you find them!

2. The western world, whose reign is coming to an end as power moves slowly towards Beijing? -- seems inevitable, though I suspect we will see a few surprises. Musk might be buying TikTok as we speak.

3. The human world as such, marking the end of the Anthropocene? -- terrifying, but it's also going to happen at some time isn't it? Fires in LA and floods in Chennai are passe - here's a new sign of the empire ceding territory: fertility rates are dropping faster than anyone imagined.

Of the three, at least the first two can be legitimately termed ‘hegemonic,’ i.e.,

Antonio Gramsci developed the concept of "hegemony" to explain how a dominant group in society secures and maintains its power. Rather than relying solely on coercion or force, Gramsci argued that ruling classes achieve hegemony by shaping cultural norms, values, and beliefs in ways that make existing power relations seem natural, inevitable, and beneficial to everyone. Note within the note: The carrot always comes with a stick - both neoliberal and western hegemonies were backed by force, often genocidal force.

By the way, the Gramsci quote at the beginning of this section is from a loose translation by Zizek; a more literal translation of the same prison note says: "The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear."

Interregnum: Originally, the term interregnum comes from the Latin for "between reigns" (inter = between, regnum = reign). In ancient Rome, it referred to the time between the death (or abdication) of one ruler and the accession of the next. During an interregnum, the usual structures of power are in flux, and leadership is not firmly settled. Antonio Gramsci used interregnum metaphorically in his Prison Notebooks to describe a historical moment or phase in which the old order (or hegemonic formation) is losing its capacity to rule effectively, but a new order has not yet fully established itself. This creates a period of uncertainty and crisis--a "vacuum of hegemony."

The new order, when it finally arrives, will be ruled by a monster that emerged from the deep during the interregnum. I don’t know what the monster will look like, but what I am sure is that it will be a planetary monster whose anatomy and physiology will be studied by future bhumists.

How does one study monsters?

While we await a complete theory of Bhumics, we can draw insights from philosophical myths of times past. During periods of transition, speculation becomes our primary tool for understanding - which explains why many important works from these periods are speculative in nature.:

Plato’s Republic

Machiavelli’s Prince

More’s Utopia

Hobbes’ Leviathan

Rousseau’s Social Contract

On a personal note, I read the Republic and the Social Contract a long time ago and the Prince a long long time ago when I didn’t have the maturity to understand it. I have never read More and Hobbes.

Not that they are all written as fables, but even when they are sober, they are unleashing a new monster upon the world: indeed, all five books have a monster for its title. I am not seeing my work as commentary - at some point we have to stop using Leviathans and Utopias to grasp our current situation, for Hobbes’ and More’s interregna (is that the right plural?) aren’t the same as ours. We can profit from their mode of thought, even if we set aside their labels, arguments and conclusions.

If you see a monster on the road, kill him.

But none of these five beasts make sense without two monster-slayers navigating us through the interregnum:

Cervantes’ Don Quixote - for Monsterology

Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy - for Affectology.

That’s a lot of reading! There’s no escaping the tyranny of text.

Silicarbon

While I am going to major in Affectology and Monsterology, I am planning on pursuing a contemporary topic in Bhumics as a minor.

There are many elements that constitute through the Anthropocene: we produce more Ammonia than all natural processes put together, for example, but if I had to pick the two ruling elements, they are:

1. Carbon

2. Silicon

One is at the heart of energy production and the other is at the heart of information production. If the Anthropocene is composed out of the twin strands of energy and information, carbon and silicon are the ruling elements for those two activities.

Of course, I am not saying the most valuable activities are the ones that produce carbon or silicon (or in the case of carbon, reduce it); both gasoline and plastics are downstream from crude oil and chips are a product of arguably the most complex manufacturing process ever. Carbon may be more versatile than Silicon, for it’s there in gasoline, in plastics and other petrochemicals. In contrast, Silicon is best known for its use in chips, solar panels and breast implants.

Nevertheless, these two commodities are at the heart of most things that matters today. Chips make money, power data centers, lead to better AI algorithms and are subject to export controls and sanctions: in other words, everything from economics to science to politics to geopolitics. To which oil can add wars and climate change (can’t say it’s associated with bleeding edge scientific advances of the same order as chips though).

Consider the economic gravity of these two materials. The global semiconductor market surpassed $600 billion in 2022 and is projected to reach over $1 trillion by 2030, with AI-driven demand increasing exponentially. Meanwhile, the fossil fuel industry remains a $7 trillion behemoth despite efforts toward decarbonization. While the logic of carbon is depletion--burning through finite reserves--the logic of silicon is acceleration, with Moore's Law still holding in some form even as we approach the physical limits of miniaturization.

To give you sense of the insanity, Microsoft plans on investing $80 Billion in AI in 2025 - 80 billion in just one year. Which reinforces my belief that AI is the most capital intensive technology ever, and will lead to an even closer marriage (conspiracy?) between the State and the Market, both in the US and in China.

The first Cold War was about fissile elements, but this second Cold War, the one that will define the next phase of the Anthropocene, will be arrayed around these two. You might say the US won the 20th century by being the main deployer of carbon, but then it discovered silicon and shifted one row down the periodic table, while China is now the leading consumer and reducetarian when it comes to Carbon while playing catch-up in the Silicon stakes.

But here's where the analogy between the two becomes more than a metaphor: both elements depend on extraction, refinement, and an intricate web of dependencies. Just as oil-rich regions have been sites of geopolitical contestation, so too are the chokepoints of the semiconductor supply chain--Taiwan, South Korea, and the Netherlands--now battlegrounds of a different kind. The U.S. has waged a silicon war through export controls, seeking to deny China access to advanced chip-making technology. In response, China has poured billions into indigenous chip production, though it still lags behind Taiwan's TSMC and the U.S.'s Nvidia in cutting-edge design.

Yet, the Cold War analogy has limits. Unlike nuclear deterrence, which was based on mutual assured destruction, the new struggle is asymmetrical: silicon rewards control, carbon punishes excess. The U.S. remains dominant in chips, but China's vast manufacturing ecosystem gives it leverage over carbon-intensive industries, from battery production to steel and cement. Moreover, China is pivoting toward renewables at an unprecedented scale, adding more solar capacity in 2023 than the rest of the world combined. If the last century was won by controlling oil, the next will be shaped by who best orchestrates the transition away from it--without losing the silicon race in the process.

If the Bomb was the monster unleashed in the previous century, then the chips and emissions are monsters growing in size and influence in this one - not merely technological phenomena but organizing principles of the global order. Carbon fuels the economies of scale that have underpinned industrial capitalism, while silicon enables the economies of scope that define digital capitalism. Their interplay is not just about material dominance but about power in its deepest sense: the capacity to shape the present and the future.

Summary

Human life has always been intertwined with the rest of life on this planet; climate change likely ended the Harappan civilization, epidemics have changed the course of history on many an occasion, and some think geography is destiny. The building blocks of planetary consciousness have been around for the last fifty years, but it’s only now that we can realistically imagine our planetary future as the only future worth having. To repeat what I said earlier:

Planetary politics and planetary culture may not become the norm in my lifetime, or even in my daughter’s lifetime, but it’s now possible to think of them as actualities.

Liked it a lot. For one, after a long time I read something by you whose logic and language I could follow from the beginning to the end. Second, a planetary political-economy, an aesthetic and an ethics is slowly, very slowly, taking shape where reasoned discussions take place. Bhumics is the right interdisciplinary response at the right time. It is only the emergence of Bhumics that can finally dismantle the toxic affect of nationalism and make the humans more of a whole (I don't expect it to ever be complete) to make them focus on constructing a different kind of self-hood that will require a different, planetary-level, defense.

Realising the collective activity of all life forms in sustaining our planet is the way forward. The best interest of the planet should be our priority, I’m curious to learn more on what factors or cognitive biases prevent us from thinking about planetary consciousness/culture/politics!