I have an extra essay this week - I have been thinking about how “Polycrisis,” the term du jour of the past five years is already obsolete, and should be replaced by “Polyconflict,” and decided it’s better to share right away than to wait several weeks before I finish writing about RBIO and then the Pauper.

Introduction

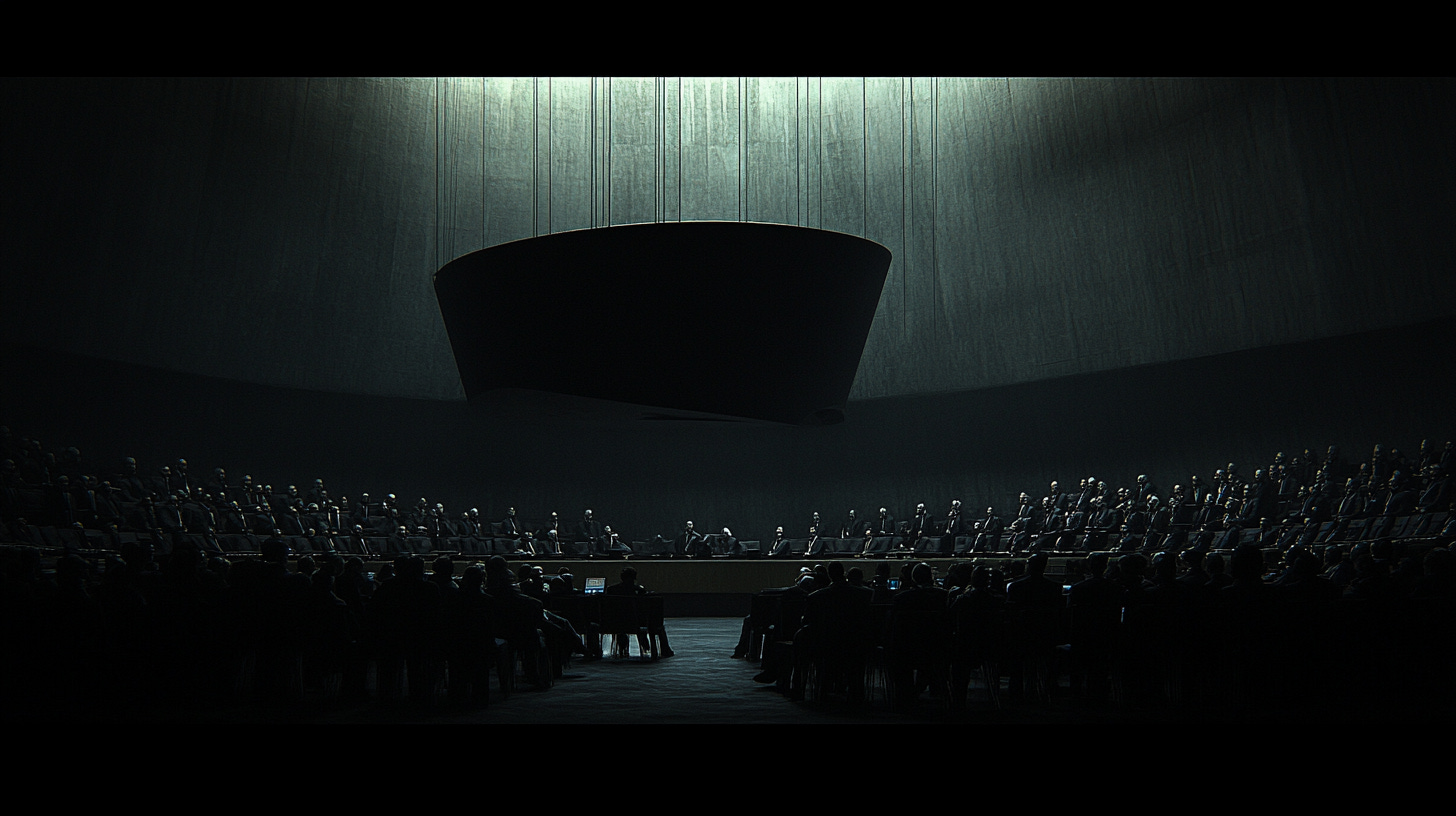

In recent years, the term "Polycrisis" has gained traction as a way to describe the complex and interconnected crises that define our contemporary world. From economic instability and accelerating climate breakdown to biodiversity collapse, resource depletion, geopolitical conflicts, and technological disruptions, the challenges we face today do not exist in isolation; they interact, amplify each other, and create conditions that make conventional problem-solving difficult. The notion of a Polycrisis captures this complexity, emphasizing how multiple crises intersect in ways that exacerbate their individual effects.

However, this framing carries implicit assumptions that require scrutiny. The term "crisis" suggests that these disruptions are temporary, exceptional, and ultimately resolvable through established managerial techniques and institutional responses. But what if the world is not merely experiencing a series of crises that can be managed and overcome? What if we are instead facing a fundamental transformation of global order—one that is not about crisis resolution but about widening conflict?

TLDR; the concept of Polycrisis is inadequate for describing the realities of 2025. Instead, we must shift to the concept of "Polyconflict," which better captures the enduring, structural nature of contemporary global challenges. Unlike crises, which imply a moment of acute instability requiring resolution, conflicts are ongoing struggles for power, resources, and survival. Understanding the world as a Polyconflict, rather than a Polycrisis, forces us to rethink governance, strategy, and resilience in ways that acknowledge the permanence of instability and the necessity of adaptation.

Polycrisis Primer

The term polycrisis originated in the work of French philosopher and sociologist Edgar Morin, who introduced it in his 1993 book Terre-Patrie (translated as Homeland Earth1) as part of a broader critique of modernity’s fragmented approach to global challenges18. Writing in the aftermath of the Cold War, Morin observed that the accelerating interconnectedness of economic, ecological, and cultural systems had created new vulnerabilities.

He argued that crises in one domain—such as financial instability or environmental degradation—could no longer be isolated but would inevitably propagate across systems due to globalization’s tight coupling. Morin’s insights drew heavily from complexity science and systems theory, emphasizing nonlinear interactions and feedback loops that transform localized disruptions into global emergencies.

While Morin’s formulation initially remained niche, the concept gained traction in the early 21st century as scholars grappled with the 2008 financial crisis, climate breakdown, and geopolitical realignments. It gained significant attention and popularity more recently, largely due to historian Adam Tooze, who used it to describe the interaction of multiple crises occurring at once. The term has since become a key descriptor for the interconnected nature of global challenges and was prominently featured at the World Economic Forum in 2023, highlighting its relevance in today's global context.

The Limits of "Polycrisis"

The term "polycrisis" combines two key ideas: "poly," denoting the interconnectedness of multiple issues, and "crisis," which traditionally implies a temporary rupture requiring urgent response. This term has been useful in highlighting how various global disruptions—climate change, economic downturns, geopolitical tensions—do not exist in silos but instead reinforce one another in unpredictable ways. It suggests that tackling one crisis in isolation is futile if its causes and effects are tied to a larger web of instability.

However, the core assumption behind the term remains rooted in crisis thinking, which implies that these disruptions are exceptions to an otherwise stable system. The language of "crisis management" reinforces this notion, suggesting that with the right policies, governance frameworks, and interventions, stability can be restored. This perspective is fundamentally flawed in at least three ways:

It assumes that crises are temporary disruptions rather than signs of systemic transformation. Climate change is not a one-time emergency but an ongoing shift in planetary conditions - one that's already locked in decades of rising temperatures, extreme weather events, and ecosystem collapse. The extinction of species, the acidification of oceans, and the destruction of crucial biomes like rainforests and coral reefs represent irreversible transformations of Earth's life-support systems. Economic instability is not a momentary fluctuation but a feature of an increasingly fragile global system. Geopolitical tensions are not isolated incidents but long-term power struggles between competing interests.

It suggests that solutions can be found within existing institutional frameworks. The crisis management approach assumes that governance, diplomacy, and economic regulation can successfully address these issues. Yet, time and again, we see these institutions failing to contain instability. Whether it is international climate agreements that fall short of meaningful action or economic policies that exacerbate inequality, the tools of crisis management are proving inadequate.

It fosters a false sense of control. By framing global challenges as crises that can be solved, the term "Polycrisis" encourages a belief that with the right expertise and coordination, the world can return to stability. This ignores the reality that many of these conflicts are not problems to be solved but struggles to be navigated.

The limits of ‘Polycrisis’ thinking are arguably the limits of Complexity Science/Complexity Theory as well, for the science in Complexity Science assumes that complexity can be measured and managed. Measurement and theorizing could hold true even if the crisis turns into conflict, but ideologically, the Polycrisis is the appropriate object of Complexity Theory’s attention since they are both part of the same ‘liberal’ approach to systems.

I have been a complexity theorist for a long time, but for the first time I am feeling we have reached the limits of its current insights. I am feeling the same anxiety about Cybernetics, another favorite of mine over the years.

And I think I know the reason: the raison d’etre of Complexity Science/Cybernetics is the ‘Bird’s Eye View’ while I have been moving towards the ‘Earthworm’s View’ for several years now.

From "Polycrisis" to "Polyconflict"

The Polycrisis was a reasonable diagnosis of the ancien regime, but we are now in the interregnum. Not quite the ‘war of all against all’ but nevertheless closer to the Italy of the late 15th century which prompted Machiavelli to write the Prince, than to the Rules Based International Order.

The concept of Polycrisis is inadequate to the world we inhabit today. What should replace it? I propose "Polyconflict" as a more accurate framework for understanding contemporary global disorder. Unlike crises, conflicts are not disruptions that demand resolution but ongoing power struggles that shape the world order.

Why "Polyconflict"?

The transition from Polycrisis to Polyconflict reflects a recognition that the global landscape is not simply experiencing a series of crises but is undergoing deep structural shifts characterized by enduring tensions. Several key features define this transformation:

Power Struggles Define the Global Order: The phrase "the strong do as they will, and the weak suffer as they must" aptly describes the current geopolitical reality. From great power competition between the United States and China to regional conflicts where authoritarian regimes consolidate power, the world is increasingly shaped by the exercise of brute force rather than cooperative governance. This is particularly evident in conflicts over dwindling resources, from water wars and land grabs to competition for critical minerals needed for green technology. As climate change intensifies, we're seeing increased military positioning in the Arctic (hello Greenland), disputes over newly accessible shipping routes, and conflicts over arable land in regions affected by desertification.

Zero-Sum Thinking Prevails: Unlike the cooperative frameworks that characterized the post-Cold War era, today’s international relations are increasingly shaped by sovereigntist, mercantilist, and transactional logic. Nations prioritize self-interest, protectionism, and competition over collective problem-solving. This mindset is especially dangerous in planetary matters, where nations prioritize short-term economic gains over collective ecological survival. The tragedy of the commons plays out on a global scale as countries race to exploit remaining fossil fuel reserves, even as science clearly shows these actions threaten civilization itself.

Political Conflicts Extend Beyond Economics: The competition for resources is no longer limited to markets and trade. Political power has become central to survival, with governments increasingly viewing governance as a battleground where seizing control means suppressing the opposition, dismantling checks and balances, and entrenching dominance.

Managerialism is Insufficient: The challenges of a polyconflict world require more than just technocratic solutions. Stability cannot be restored through policy tweaks and institutional adjustments alone. Instead, navigating this era requires a new level of strategic adaptability, resilience, and in some cases, outright aggression.

Implications of Polyconflict for Governance and Strategy

Understanding the world as a polyconflict rather than a polycrisis carries profound implications for how we approach governance, diplomacy, and security.

1. Governance Must Shift from Stability-Seeking to Adaptability: Traditional governance assumes that stability is the norm and disruptions are exceptions. In a Polyconflict world, governance must be reoriented toward managing long-term instability rather than attempting to restore a lost order. Now that it’s clear we will not have a global climate accord of any kind, we must be prepared for permanent changes like rising sea levels, regular extreme weather events, and mass migration from increasingly uninhabitable regions. The idea of "normal" weather patterns or stable ecosystems is quickly becoming obsolete.

2. Conflict Resolution Over Crisis Management: The focus must move away from emergency responses toward long-term strategies for navigating entrenched conflicts. This means acknowledging that many global struggles—whether over climate policy, migration, or geopolitical influence—will not be "solved" but must be continuously managed.

3. Resilience is a (the?) New Currency of Power: Societies, institutions, and economies must build resilience to withstand ongoing shocks. This requires diversifying energy sources, strengthening supply chains, and developing decentralized governance structures that can function under prolonged stress. Climate resilience has become particularly crucial, requiring cities to redesign for extreme weather, agriculture to adapt to changing growing seasons, and infrastructure to withstand unprecedented environmental stresses. Nations must prepare for cascading failures where climate disasters trigger food shortages, which in turn spark political instability and migration crises.

4. Decentralization and Localized Solutions: Given the unpredictable nature of Polyconflict, relying solely on global institutions is no longer sufficient. Local governance, regional alliances, and community-driven initiatives will play a critical role in managing instability.

5. Strategic Realism Over Idealism: In a world of Polyconflict, wishful thinking must give way to pragmatic decision-making. This means accepting that not all conflicts can be mediated, and in some cases, hard power will be necessary to protect national and community interests.

Conclusion

The concept of Polycrisis has been useful in articulating the complexity of global challenges, but it ultimately falls short by implying that these disruptions are temporary and solvable within existing frameworks. In reality, we are not living through a series of crises but through an era of persistent and intensifying conflict—one that cannot be managed away but must be strategically navigated.

By shifting from polycrisis to Polyconflict, we acknowledge that the world is not experiencing temporary turbulence but a profound transformation in how power, governance, and survival operate. This shift demands a fundamental reevaluation of how societies prepare for the future, how governments structure their policies, and how individuals and communities build resilience in an increasingly unstable world.

The environmental, planetary aspect of the Polyconflict is perhaps its most fundamental feature. Unlike political or economic conflicts, the laws of physics and biology cannot be negotiated with, and tipping points in Earth's systems, once crossed, cannot be uncrossed. The melting of permafrost, the die-off of coral reefs, and the collapse of pollinator populations represent irreversible changes that will reshape human civilization regardless of our political or economic responses. These environmental transformations will intensify existing conflicts while creating new ones, from disputes over geoengineering to battles over remaining habitable territories.

The world will not return to stability as we once knew it. The challenge ahead is not to restore a lost order but to learn how to survive and thrive in an age where conflict, not crisis, is the defining feature of our time.

Morin, E. 1999. Homeland Earth: A manifesto for the New Millennium. New York: Hampton Press.

Sir, it was an honor to meet you at the Litfest today. Philosophical mathematicians are rare and I absolutely love your writing as much as I loved hearing you! Look forward to connecting and collaborating! 😊

Regards

Trisha