Bhumics demands we integrate climate, ecology, and human ambition into a single framework, but there are many ways of doing so. As ‘positive scientists,’ some Bhumists might recommend monstrous proposals like geoengineering or naked resource grabs. But other Bhumists like us can also critique these monsters, forging new planetary realities while setting inherited dogmas aside.

Machiavelli has a Machiavellian reputation for ruthless immorality. But isn't all science amoral? When climate activists claim that physics doesn't care about your silly political games, they are using Machiavellian reasoning to their ends. But so can the other side! If physics is going to dictate an ice-free Arctic, everyone from Trump to Putin is going to ask themselves how they will benefit from the newly open ocean lanes. From the earliest days, the Arctic was iced over and of little interest. The scramble for Greenland is just one example of the planetary-scale competition to come.

Machiavelli: a man who understood defeat intimately--tortured by the new regime, forced into retreat, and eventually producing _The Prince_, a treatise shaped by the bitter knowledge that fortune is fickle. Today, we face a similar crisis of liberalism, a mood that once felt inevitable but is now undone by the rise of transactional geopolitics and soon, transactional planetary politics.

Machiavelli's "positive" approach, akin to the distinction between positive and normative economics, can be useful: sometimes we must see the world without moral illusions, observing the forces at play. Machiavelli would immediately recognize that the rise of AI and the effects of climate change have created a new level of volatility and unpredictability in global affairs. Just as he saw the shifting power dynamics of Renaissance Italy, he'd view these forces as the new "fortuna," capable of drastically altering the course of nations.

In case you want a quick intro to Machiavelli’s thinking, listen to this podcast that I created using NotebookLM.

The Machiavellian planet

For the longest time, which is to say, from before the dawn of history until today, the North Pole was covered by ice for much of the year. Therefore, we imagine the North Pole as this cold place where nothing happens, where you have an ice cap that prevents people from having permanent lives and an absence of economic activity and geopolitical competition.

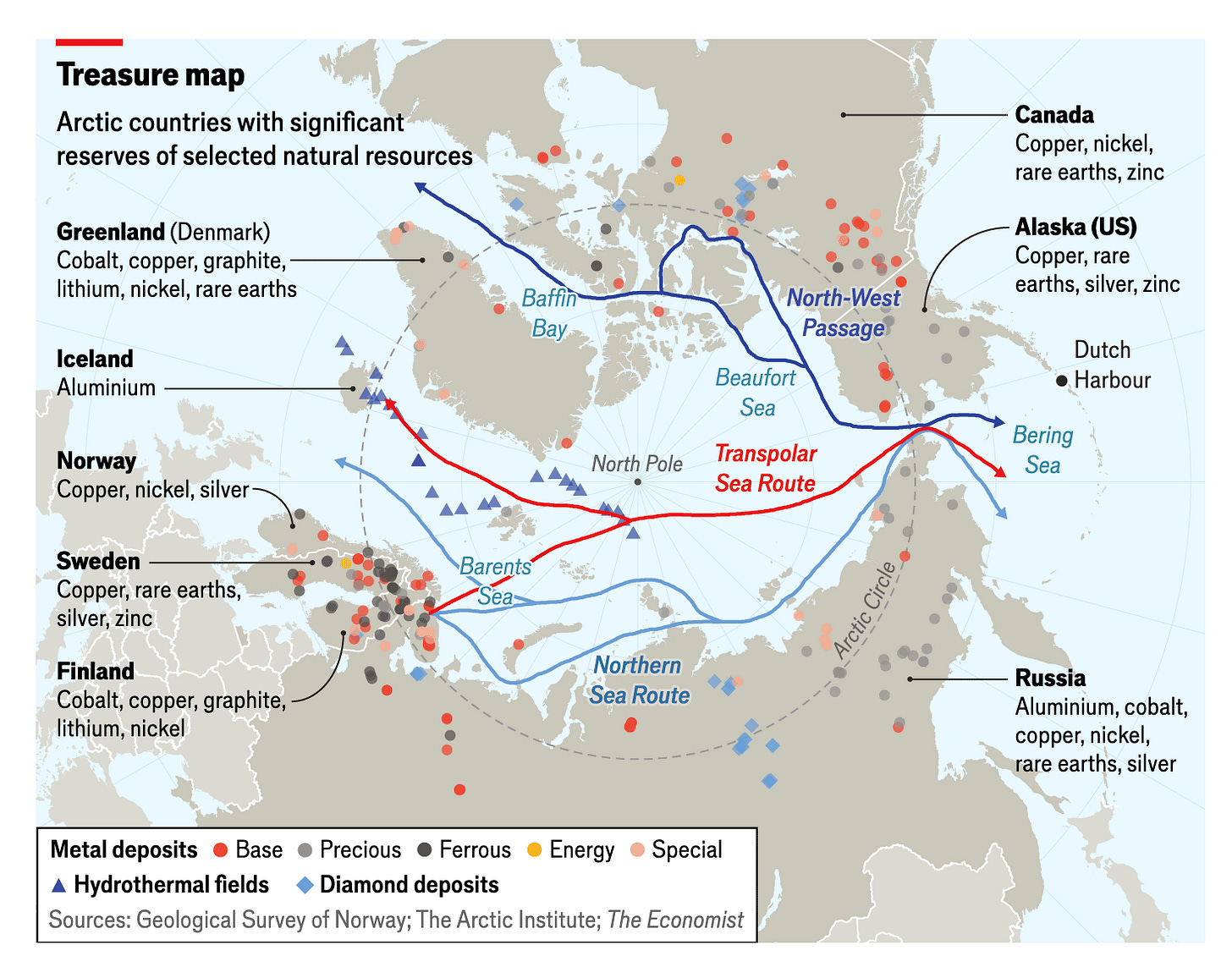

The Arctic is considered ice-free when sea ice extent drops below one million square kilometers, though small patches of ice near Greenland and northern Canada may persist. Recent studies suggest the first ice-free day could occur as early as 2027, with some models predicting it could happen before 2030. This event would likely occur during late summer, typically between August and September. 2027 is almost here, and an ice free arctic then will be within the ambit of this incoming presidential administration. No wonder Trump wants to buy Greenland, because it's not just a question of national security. We're talking about much economic interest, perhaps even a capacity to settle people and well before that, dig for valuable stuff.

When I was first thinking about ‘Bhumics’, I imagined it as an expansion of our moral and political universe to include the planet as a whole. Or at a more operational level, planetary considerations at every scale - from international emission control negotiations to local governments having climate budgets. That’s what I want, but it could well be that we start this journey at the other end of the spectrum: if and when planetary politics become normalized, which I think it is starting to, it doesn't have to be normalized in the ‘Earth is our Mother’ way at all. It could be normalized in a ruthless fashion: that every aspect, every location, every ecological niche, every thimble of pond scum (in short: the Earth as a whole, from cells to continents) becomes the arena for intense competition.

We need ways to think about both ends of the Bhumic spectrum - planetary concern and planetary competition - from our current interregnum. Imagine a war or catastrophe in the next 50, 60, 70 years, which will kill off a billion people. Let's say 10% of humanity is gone and another 20% made destitute. Is it is this an apocalypse? Arguably not, for it’s not the end of the world, but it’s going to have mind-boggling consequences.

About 20% of Europe died in the Thirty Years War, so it’s not as if we haven’t seen such loss of life.

We need to prepare for strife and defeat, and no better place to start than with Machiavelli.

The Prince of Defeat

I like how Machiavelli stares at me from across the abyss. He looks well-fed, or as we would say back in my youth, healthy, when not too many people were healthy. The head on top of his healthy shoulders is lean and hungry, a man who had once been at the center of power. From 1498 to 1512, Machiavelli served as the Second Chancellor of the Florentine Republic, conducting diplomatic missions across Europe and establishing Florence's first standing army. He was, in modern terms, both a senior civil servant and diplomat, serving the Republican government that had expelled the powerful Medici family.

But fortune's wheel turned in 1512 when the Medici returned to power with Spanish military support. Machiavelli, the loyal Republican servant, was dismissed from his post, arrested on suspicion of conspiracy, and subjected to torture by strappado—his arms tied behind his back and his body dropped from a height, dislocating his shoulders. Though he maintained his innocence and was eventually released, he was exiled from Florence to his family's small estate in Sant'Andrea in Percussina.

It was in this enforced retreat, this painful separation from the political life that had defined him, that Machiavelli wrote his most influential works. During his days he would work in the fields or wander the countryside; in the evenings, he would don his old court clothes and commune with the ancient political writers in his library, producing The Prince, The Discourses on Livy, and several plays. His exile was both a personal catastrophe and an intellectual liberation—freed from the daily compromises of political service, he could write with unprecedented candor about the nature of power.

There is another image of him from later, from an 18th century sketch of an older Machiavelli who has seen the horrors of the world. Some might say that he added to its horrors, but I want to be able to read him as a person who foresaw the the truth of the horrors he saw and the horrors yet to come.

I want to talk about defeat.

The last ten years have been a decade of political defeat - though the political is personal, so it’s also a personal defeat. Until then, say until 2014 when Modi took power in India and 2016 when Trump was first elected in the US, it felt like some version of liberalism lay at the end of history. Liberal imperialism isn’t fun for those at the receiving end of civilization (see figure below), but from the inside, liberalism always felt like ‘progress in fits and starts’ throughout my life until this past decade.

The Gandhian independence struggle was a liberal movement (I am using ‘liberalism’ broadly and maybe it won't sustain criticism, but let's just call it liberalism for now). And through it, I could unselfconsciously adopt the posture that India was a great civilization and that it is through that civilization's greatness that we are a liberal nation. Similarly, in the United States, I felt that, maybe I'm a minority, but nevertheless, I am aligned with the broad values of the country, that the people who matter will embrace someone like me. Both of these homilies are false now. Liberalism as a general mood of tolerance and progress has been defeated. It may still win elections, but it’s no longer the default.

And in this defeat of liberalism, I'm also talking about the defeat of liberalism as a mood. You know, like in the previous essay, I talked about how Bhumics should be a mood, an Affectology as much as an Ideology. In the same way, I experienced liberalism as a mood, a collective unconscious below the level of culture and definitely below politics.

The passing of a mood deserves an emotional response.

We have to embrace the defeat of liberalism as a mood. Not to throw our hands up in despair, or even with resignation but with a kind of reflective assessment that the world has changed. Permanently?

Like Machiavelli did after the republic fell. And then the new regime fired him, tortured him and kicked him out. There he was on his father's estate, alone, without powerful friends, having to write a text that would be one of the more ruthless texts about politics ever written.

We cannot enter into the mind of ‘The Prince’ until we accept that we too have been defeated.

Gotta say there's a lot of famous retreat literature from those times. Besides Machiavelli, Montaigne and Descartes composed their famous texts in retreat, in seclusion. Maybe because they were all active members of the world first and it's hard write at length while active. But it may also be that in an interregnum - all three are representatives of the interregnum between the medieval and the modern - you need seclusion to replace the vanishing world with the world yet to come.

To think the new world.

All three are crafting a new kind of person. The seclusion helps them do so. That new person shocks the world in ways that invite harm and in ways that generate harm. Descartes was worried about his doctrines displeasing the authorities. Machiavelli's doctrines shocked the authorities in their ruthlessness. And Montaigne, the most decent of the three, crafts a self that did not exist before the time that they were writing.

The Leviathan in Retreat

One of the advantages of liberal hegemony was that even non-liberal actors had to take the liberal position as the default. And as a result, there was always the opportunity for the liberal to say “our way is better.” Or if the opponent was weak, unleash the imperial wing of liberal hegemony and change their regime. This was, in a sense, the good cop, bad cop version of liberal power.

Not too long ago, I read an article about how China’s influence in Latin America is increasing because the Chinese aren’t interested in ideology; they only want to make a deal. That’s arguably the stance of Trump’s America as well. And this is what leads to the sense of defeat among liberals, right? That our way of being the world, which was felt as superior, is no longer the default way. It doesn't have the normative attraction that it used to.

If the first Cold War was between two strongly held ideological positions, will the second one consist of deals going sour? Transactional international relations might - and I want to emphasize the ‘might’ - put a stop to the endless wars of liberal imperialism, but what new monsters will it unleash?

The impending competition at the North Pole is a hint of times to come: the Chinese are building massive ice-breakers, but they will need bases closer to the pole, which means intensifying need for ports in the Russian north. Russia itself may not have the money for expanding its Arctic fleet, but it may be wary of giving China access to its northern periphery. In any case, massive increase in trade and military activity at the North Pole will make ecological catastrophe and climate collapse more likely. But some people will survive and thrive even then, and it looks like influential parts of our political economy are (tacitly, if not explicitly) moving in that direction.

Positive Bhumics

Machiavelli’s aura of immorality prevents us from seeing him as a pioneer. Whether you agree with M or not, there’s value in learning to see the world in a purely instrumental way, to create a positive science for the acquisition of power and wealth with no reference to a moral framework that governs that instrumental rationality. Google the difference between positive economics and normative economics.

Instrumentality about wealth and power is the default today and many argue that we have reached great levels of prosperity and well-being as a result of this ideology: a secular, power-maximizing, wealth-maximizing framework. I don't agree - I don’t think we have achieved wealth and power through these ‘positive’ means alone, but its an argument worth taking seriously. We don't have to believe in Machiavelli to acknowledge there's something useful about the style of analysis that he inaugurated. We can use Machiavelli as a purva-paksa, an opponent whose perspective you have to take seriously.

And for our purposes, if we expand human affairs to a planetary scale, we can look at all planetary processes - not just social or economic, but also climatic, biophysical and geological - in a ‘positive’ framework. A planetary systems framework that achieves wellbeing for both human beings and other species without inserting existing moral ideas into our assessments.

Machiavelli would likely emphasize the need to treat climate change as a major threat, encouraging aggressive investment in adaptation strategies and renewable energy technologies. A prince cannot rely on the "beneficence of nature."

In my view, if we want to grasp the planet and to grasp the planetary age that we are in, we don't want to be overburdened by existing moral, political, social frameworks because we're going to have to rethink all of them. We don’t have to be amoral, but at the very least, we have to let the normative to emerge in conversation with the positive.

Machiavelli intuited the new age that Europeans were entering—the age of secular competition between nations and then in the future, corporations. We need to cultivate our planetary instincts. Taking ‘positive bhumics’ seriously will take us in directions I find unpleasant - geoengineering, for example - but we should approach these solutions in the spirit of Critique, i.e., in the spirit of the subtitle to Marx’s Capital - “A Critique of Political Economy,” instead of broken ideals from a defeated world.

Kahani mein twist. The first part did not give any inkling that you would swerve toward Machiavelli to propound a "positive" approach as opposed to a "normative". Because after defeat comes reflection (that is if you are still standing) to figure out where we stand, with no illusions, no idealism -- just cold hard facts and what they imply in terms of action.

But you are not entirely taking leave of morality are you. Because once the period of reflection is over, comes the time for action, which is by definition conflictual. And any conflict gives rise to moral issues. We will certainly need to reconfigure our moralityscape, but some issues of morality and justice are timeless, aren't they.