In my previous essay, I introduced the concept of cosiety and suggested it’s a better framework for understanding the ‘pillars of Indian society’ such as caste than the concept of society itself. The first step is to reveal traces of the cognitive in all aspects of the social, both as:

the instrument through which human collectives are understood and

as collective experiences that can’t be contained within the social bucket.

TL;DR: Cosiety is a newly forged hammer and as Thor-in-chief, I am roaming the earth in search of nails.

The Social Abstraction

Suppose you were to poll a hundred Indians – laypeople, academics, politicians etc – what they thought caste was, chances are the answers you will get are of the following kind:

It’s a universal system of hierarchy and domination. Perhaps not expressed in this intellectual jargon, but nevertheless a system that places people on a ladder.

It’s a hereditary system that constrains who you are, what you can do, whom you marry, what you eat and where you live.

In the modern era, it attaches itself to political life, access to the state and a new regime of redistribution.

In all three assessments, the social dominates. Whether we look at how caste is represented in popular discourse, in academic debate or in political contests, caste appears to live in a world populated by humans alone with a few objects serving as props to the human drama. ‘Who dominates whom,’ ‘where did my caste come from?’, ‘who is winning and who is losing’, ‘who gets the jobs’ (and why don’t I when I am so meritorious): these are the controversies on the ground, in parliament and in boardrooms.

It’s as if a theory of caste has become the perception of caste. Perhaps theory is the wrong term if we can only use it for ‘objective’ representations of the world, but if by theory we mean structured abstractions that:

Denote ‘reality’

Regular perception and action

Are available for reflection

Then all of are theorists of caste who share (more or less) the same social abstraction.

There’s nothing wrong with theories; by their very nature, theories abstract from the messy details of the world in order to understand the relationships between a selective set of features. For example, if I am studying gravitation in the planetary system, I might idealize the sun and the planets as points with no extension. No solar flares, no spots on Jupiter: only dots. That idealization, in turn, helps us understand the motion of the planets around the sun, which is the topic of interest.

In the same way, we can abstract out the physical and environmental features of the world from caste, leaving only humans who play games of domination and submission with each other. That social abstraction is powerful, for it helps us understand the structure of caste as a social system; it makes us ask important questions about how religious imagery (the famous head-trunk-feet of the mythical Purusa for example) interacts with every day reality. It also helps us understand how caste dynamics work: which jati is moving where and how that jati is negotiating power relations with other jatis on its way up or down.

What’s missing?

The social analysis of caste (in all three arenas: street, academy, parliament) presupposes the social abstraction, which can be assumed to be a model of caste in equilibrium. ‘A system in equilibrium’ is a concept borrowed from thermodynamics, to mean a system that isn’t influenced by the outside world and any changes it experiences are dues to internal motions. Therefore caste in equilibrium would mean a world in which caste isn’t affected by influences from the outside and any changes in caste structure are due to internal adjustments.

One step beyond equilibrium lie slow, long term influences stemming from changes in the political economy and the relative value of resources to which a caste might have preferential access. Here, we can continue to keep the theory, but add ‘outside forces’ as a means of change. For example, Jats and Yadavs have risen relative to Rajputs because of the increasing value of land and the decreasing value of armed combat. As a result landowning and farming castes have greater capacity to mobilize and bargain for power.

Bigger problems arise with changes that are relatively far from equilibrium, where the outside world makes insistent demands on the caste system on an ongoing basis. For example, with the increasing influence of modernization and the market economy, new livelihoods have come into being that didn’t exist two hundred years ago: truck drivers and Whatsapp influencers for example, but also marketized versions of professions that have existed forever. Almost every security guard in Bangalore is an Oriya man – typically lower caste. Many cooks in Bangalore are upper caste Oriya men.

How do castes move into these new professions? Is that movement exclusive or do these new professions have room for multiple castes, even if they are arranged in an internal hierarchy?

It’s clear that these new livelihoods have loosened the formation of caste. Caste as an indicator of livelihood is much less secure than it used to be a hundred years ago; that’s certainly true of modern professions, which might be biased in favor of one caste over another, but don’t deny access to other castes by design. It’s also increasingly true of traditional livelihoods. When migrants – potentially upper caste! – from other states perform farm labor traditionally done by lower castes, what does it to customary social relations?

The same with politics. Everybody agree that mobilization on the basis of caste has been enormously successful in what was imagined as a constitutional democracy composed of liberal individuals. Why so? Why has it been so easy for caste to move into this new cognitive niche? How did political and state identity become a central feature of caste so quickly?

Even the aspect of caste most resistant to change – endogamy, i.e., within-caste marriage – has changed more in the last hundred years than in the previous thousand. In this combination of conservatism and flexibility, caste is showing that it’s a learning system and not just a static system. The movement into new niches is not just an outcome of changes in the political economy: in pursuing new opportunities, castes create the material system that sustains them from that point onward.

In doing so, we see the beginnings of an important phenomenon: instead of caste disappearing as a result of modernity, it survives and even flourishes by becoming more flexible. We may want caste to be annihilated, but it may adapt to its new circumstances instead.

Caste is a learning system.

Sensationalism

Learning is peripheral to the social but it’s central to the cognitive. But it’s not just the social that’s cognitive: I want to put forth an observation that needs development as an independent line of inquiry: the material is cognitive too.

The alienation of labor is typically understood:

as the laborer lacking control over what happens to the fruit of their actions (it’s the capitalist who controls when and how the product is brought to market) and

also as the laborer being alienated from the process of production itself, when in an assembly line they are only responsible for one repetitive, discrete contribution.

But Marx’s own description of alienation leaves open a further development of the idea. In his “Comment on James Mill” he says (italics mine):

Let us suppose that we had carried out production as human beings. Each of us would have, in two ways, affirmed himself, and the other person. (i) In my production I would have objectified my individuality, its specific character, and, therefore, enjoyed not only an individual manifestation of my life during the activity, but also, when looking at the object, I would have the individual pleasure of knowing my personality to be objective, visible to the senses, and, hence, a power beyond all doubt.

While Marx doesn’t seem to think visibility is the key to alienation and it’s certainly not understood that way today, I want to bring ‘visibility’ back to the center of labor. And not just the sense of sight, but all the other senses too: smell, touch, taste, hearing. The cosial is a sensational take on the social.

Why so?

The Amazon Prime shipment arriving at my door from China in two days leaves no sensory trace. It’s origins and history are outside my experience altogether which makes it an ‘object’ whose creating subject might as well not exist. It’s invisible to the senses until the last moment when the doorbell rings and the UPS driver wants my signature. The delivered object is divorced from life and could have come from Alpha Centauri for all I know.

The alienation of labor from the senses and the sensory environment has to be added to the list of alienations. Arguably, the alienation of objects from my lifeworld comes before and underlies the alienation of labor from its fruits.

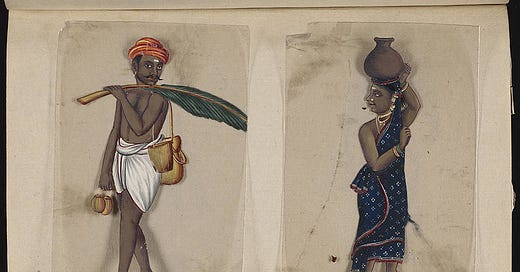

In contrast, in premodern society, not only does the laborer see the product of their labor in front of their eyes and directly sell their produce to the customer, the acts of production and consumption happen in a sensory environment. After all, almost all material that was produced, worked upon and consumed was or organic origin and therefore would have come with taste, smell, hue, and sound.

Those sensory characteristics would be central to the experience of caste. Anyone who works with animal skins or as a manual scavenger works in an intensely sensory environment and that sensory landscape is as much a part of their caste as the final product, i.e., leather. The material world doesn’t live in a hermetically sealed universe of objects but in a sensory medium. Which is to say: the material is cosial.

In revealing caste to be cosial, we are also writing ourselves a promissory note, i.e., investigate the sensory landscape of caste.

From Society to Cosiety

Once you start looking, it’s clear that caste exhibits all the characteristics of a cognitive system, a subset of cosiety rather than society. To recap, in this essay, I have developed the analysis of caste in three stages:

Stage one: caste is social. Caste as primarily a social affair in which different caste formations negotiate for power and wealth based on the cards they bring to the table.

Stage two: the social is material. Caste as embedded in a political economy in which caste formations rise and fall based on the value of the material resources to which they have preferred or exclusive access.

Stage three: the material is cosial. Caste as embedded in a cognitive economy in which caste formations cast sensory shadows, occupy new niches, absorb new political systems and learn how to behave in a new world.

As we go from 1) to 3), we are switching from Caste Society to Caste Cosiety.

Caste isn’t unique in being cosial. Cosiality is central to religion, to gender and other markers of society. Switching from society to cosiety enriches the social by bringing learning, generalization, opportunity and change as central aspects of human collectives. That switch is most obvious today when new niches are coming into being all the time, but with enough faith in our new hammer, we will see nails in the past as well.