The Planetary Animal

Aristotle says ‘man is a social animal’ - a statement to which every reader of this newsletter is likely to agree, in that all of us experience our lives as being constituted by others, people (and sometimes nonhuman people) who occupy our minds and hearts.

In the previous essay, we say what ‘social’ means - it was a particular kind of relation between otherwise non-social beings. Further, we also saw that ‘political’ was a sub-genre of the social. Here’s the adapted version:

politics is the arena where social relations are worked out, especially relations of dominance.

What about ‘animal?’ Do we know what animal means? What can an animal be if it’s possible for some animals to be political? If we accept the claim that politics is the arena of dominance relations, then at the very least the animals we domesticate for food, entertainment and science are all political animals.

In the anthropocene, perhaps all living beings are political animals, including the virus that disrupted our lives the past two years. Except that in this case, there are mutual relations of dominance.

Which brings me to a modification of the Aristotlean claim:

Humans are planetary animals.

Remember that planet is a verb for us, which means that the ‘planetary animal’ is an animals constituted by planetary relations.

Natural History

Talking about animals, we are all used to depictions of their lives as natural history. I have always loved natural history - from reading dinosaur books as a child to watching David Attenborough breathe his syllabus into the Blue Planet. But we have a new conception of natural history that comes from a very different political quarter. Here’s Gramsci quoted in Climate Leviathan:

Marxists and other social materialists have always recognized the transformative power of labour working upon the material world and capitalists appropriating the surplus produced by that labor. What’s new in the left sphere is that the material world - which is dead and inert, mostly shapeless substance - is being replaced by nature, which has its own order. Indeed, one can historicize Gramsci by saying that getting to that relationship between society and nature where one can rationally plan for the future (hence making progress possible) is itself an outcome of millennia of human control over natural processes and bringing them to a stage where we can imagine the natural world mechanically and act upon it technologically.

In contrast, the climate leviathan will extend our domination of planetary processes, managing life on earth as a whole. We will do so through geoengineering among other interventions. Is that the future we want? Even more important, is this leviathan future capable of delivering a rational, planable world?

I don’t think so

Progress as a planetary scale is deeply ahistorical, forgetting that the plenty we currently enjoy was built on the backs of genocide and exploitation and ecological collapse. We need to historicize the climate leviathan if we are to imagine a truly better world. But what kind of history do we need?

Natural history, i.e., a history in which non-human natures have agency and power, and, in fact, a history in which what it means to be human is composed out of non-human elements.

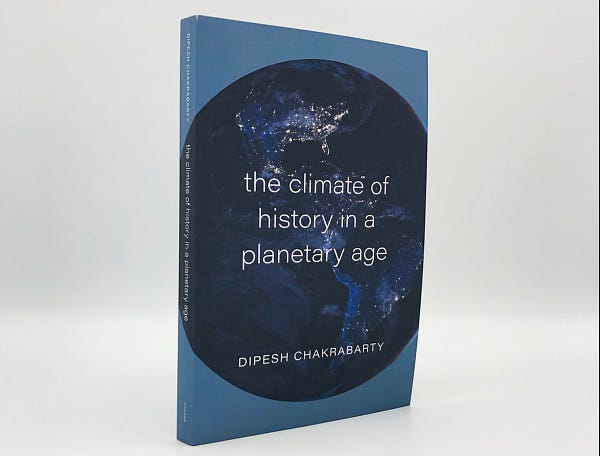

How to do Natural History in a manner that draws from Gramsci as well as Attenborough? I have no idea right now, but it’s got to be done. Which brings me to the next book I will be reading after I am done with this one: