Every Utopia becomes a Dystopia

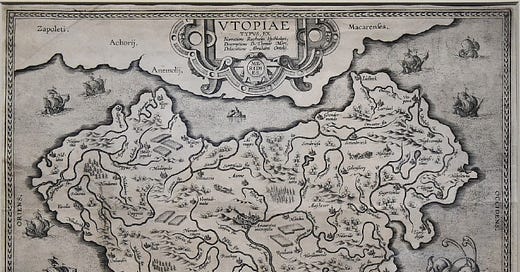

A Map of Utopia

I remember Reagan saying to Gorbachev “Tear down this wall.” Sorry, that’s fake news. Or at least white lie news. There’s no way I could have heard a live conference in West Berlin in 1987. It was probably past my bedtime in Delhi. I also have a memory of reading it in some magazine or the other. Perhaps Time. Perhaps Newsweek. Or because it was international news, I might have even read it in an Indian magazine like India Today. Frankly, since the news conference has posthumous fame — after the wall actually fell — there’s a good chance that all my memories are from reading about the event years later. When I say “I remember Reagan saying…,” I mean that the perceived importance of the event combined with my imagination has created a vivid “memory” of an event.

Well, most memory is like that. We don’t store the facts as is; instead we compress and transform every event to suit our needs. Selective understanding is crucial to living a sane life today, when we are deluged with information 24/7.

So what is a true memory?

There’s a famous thought experiment in epistemology called the Gettier paradox. Here’s a version I like:

Imagine you’re watching the 1984 Wimbledon finals with McEnroe facing Connors. Unfortunately, the broadcaster has lost contact with his TV van and doesn’t have a live feed anymore. Someone has a clever idea: why not broadcast a recording of the 1982 final instead which had the same cast?

So you’re watching the 1982 final while thinking you’re watching the 1984 final. In this version Connors wins. You go to sleep thinking Connors has won. Let’s say that Connors won the 1984 final (actually, McEnroe won in 1984; for the record, I supported Connors) and when you open the newspaper in the morning, you read the headline “Connors defeats McEnroe again.”

Your belief that Connors has won is a true belief despite being arrived at via a flawed route. Something is wrong when you can arrive at true beliefs through mistaken means isn’t it? Of course, Gettier’s thought experiment is a contrived situation. How likely is it that exactly the same type of prior event is available as a substitute for an actual one?

Tennis match twins might be hard to find but the use of memories as evidence is all too common — in testimony, in arguments between spouses, in story telling. When I tell the jury that I saw that man pull the trigger, what if never saw him shoot the victim. What if I am combining the knowledge that the man is a known hoodlum, the actual experience of shots being fired and reading headlines in the local newspaper?

Here’s the question: even if the man was the murderer, is my testimony valid? Further, if much testimony is confabulation, is any testimony valid? Especially in a murder trial where the jury is one color and the defendant another? And the final dystopian possibility — what if our social media feeds are full of posts that prime our memories to be one way rather than another. Can we trust our own minds?

I want to explore that internal dystopia in future essays. For example:

can technology help us certify memories? what would a process of certification look like? let’s say it takes the form of “bitcoin meets the brain.” Is that a techno-utopia or a techno-dystopia?

But we aren’t there yet. I am still a few decades behind that brave new world. But it does seem as if every utopia becomes a dystopia sooner or later. And then replaced by the next utopia. Let’s start with 1945. The second world war had just ended. Hundreds of millions dead, entire populations genocided, atom bombs burst.

The Soviet Flag over Berlin

Never again they said. Let’s form the United Nations and give a seat at the table to everyone. Some more prominently than others, i.e., those who were on the winning side of WWII. Decolonization started in earnest; India and Pakistan became independent in 1947, though that utopian moment happened in parallel with its own dystopian partition whose effects we feel to this day.

Anyway, the European powers who brought us two world wars lay defeated; even the victors. In their stead were two confident new powers: the United States and the Soviet Union. Each had its theory of progress, of delivering material prosperity to its citizens and eventually the world. When he said energy will become too cheap to meter we believed him. Unfortunately, that energy can flow smoothly out of an outlet or burn the sky. Even more so if you have ten thousand of them. That’s what led to:

US and Soviet tanks face off

I can’t believe how close the US and the USSR brought us to the end of times, but we were lucky; the nuclear winter never came despite several close runs. And then Reagan came to Berlin and asked that the wall come down. And it did, a couple of years after he asked!

When I first came to the US in the nineties it was an unrivaled power. For twenty plus years, it ruled the world, the most powerful country that has ever existed. It expanded market capitalism everywhere, most prominently in China but also in India. Globalization as we know it is a product of American power. I owe the writing of this essay in a cafe in Bangalore to the fall of the Berlin wall. Yes Brandenburg Gate, No Foxconn.

When 9/11 happened, the headlines across the world were “we are all Americans.” While that headline was meant as a mark of solidarity, it was truer than we think. The world of startups and markets, of Hollywood storytelling. The possibility of progress backed by global networks of influence and immense military power — who doesn’t want that in some form?

Fukuyama’s flawed masterpiece

So much so that it became possible to write a book called “The End of History” which claimed that market driven liberal democracy is the final solution to the problem of political order. In this reading, human history is a series of attempts at prosperity that collapse in violence (Rome, Han China, Gupta India) and we continue to look for a solution that combines peace and power in a manner acceptable to most.

Fukuyama thought that solution was found in 1989. Let’s call it EOH (End of History) liberalism. That we can all ride into the sunset in our Cadillacs.

Who would have thought in 1992 that the most powerful nation in history would elect Trump in 2016, that EOH liberalism would be replaced by ethno-nationalism in every major country in the world? That it would be possible for Vladimir Putin to declare in a recent interview that liberalism has “become obsolete.”

Why did that happen? Is there an intrinsic tendency for a utopian bubble to be succeeded by a dystopian abyss?

I don’t know if there’s a universal principle of that kind, but I believe it’s important to understand the internal and external contradictions that are bursting the EOH bubble. Of which two are the most important:

EOH Liberalism was deployed on networks — of goods and information — and these networks became instruments of concentration and inequality instead of decentralization and democratization that we were promised. Why?

EOH Liberalism hastened the exploitation of the nonhuman world that supports all human life and economic activity. If I may say so, it is a UX designed for easy extraction.

Could we have predicted the two? Yes, and many did, but they weren’t heard loudly enough. Perhaps because we didn’t want to hear what they were saying or perhaps because they weren’t saying it the right way.