The Clives of England

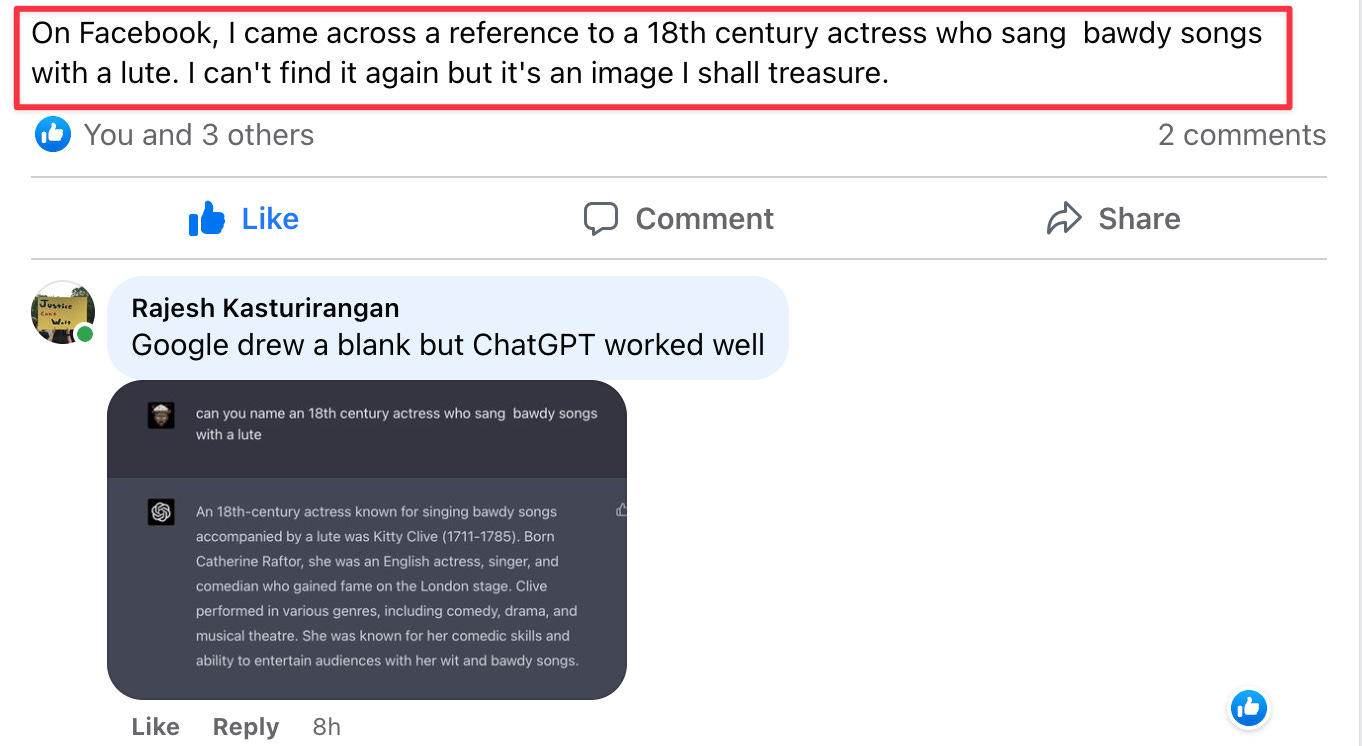

The other day I had my first AI 'come to Jesus' moment. A friend posted a question on Facebook about an 18th-century actress who sang bawdy songs with a lute. Google came up with nothing (try it!), while ChatGPT immediately gave me the correct answer.

Not only did it give me the correct answer, it allowed me to ask further questions about Kitty Clive (1711-1785), the bawdy singer. Kitty Clive was born Catherine Raftor and Kitty was her stage name. Kitty is a variant of Catherine, but the last name 'Clive' struck my fancy, for she must have been a contemporary of Robert Clive, the man who got the British Empire going in India. So I asked ChatGPT a further question:

Bummer, for I was hoping for a more intriguing answer. But no one ever complained about my lack of persistence. Why did she change her last name to Clive?

Bingo! There's a direct relationship with Robert Clive, "lord of India," a deeply flawed - may I even say, despicable - man whose statue still stands in London.

Of course, I could have Googled those questions and with enough persistence, I would have arrived at the same answers, but what would have taken an hour at a minimum took me two minutes. That's a huge increase in efficiency, and because it's rat-a-tat, it makes me want to go back and forth with the AI and explore a new terrain. In an hour or less, I can find out a lot about a class of people - perhaps even a single family - that was simultaneously prominent on stage, arguing for women's rights and despoiling and conquering other lands and setting up multinational corporations.

If I were a PhD student, it would take me less than a day to decide whether it's worth writing a thesis on a topic that's at the intersection of new freedoms (women's rights), new empires (the British) and new forms of business organization (the East India Company). I might even be able to write a thesis in a year instead of four: yes, the AI lies and hallucinates, but it gives me so many leads that I can go into the archives much better armed than before.

As of today, I can’t imagine producing a piece of written work - including this one - without going through a back-and-forth with ChatGPT or something like it. It can’t replace me (yet!), but what I can do with it by my side will increasingly be in a different league from what I can do on my own.

What's going to happen to knowledge work?

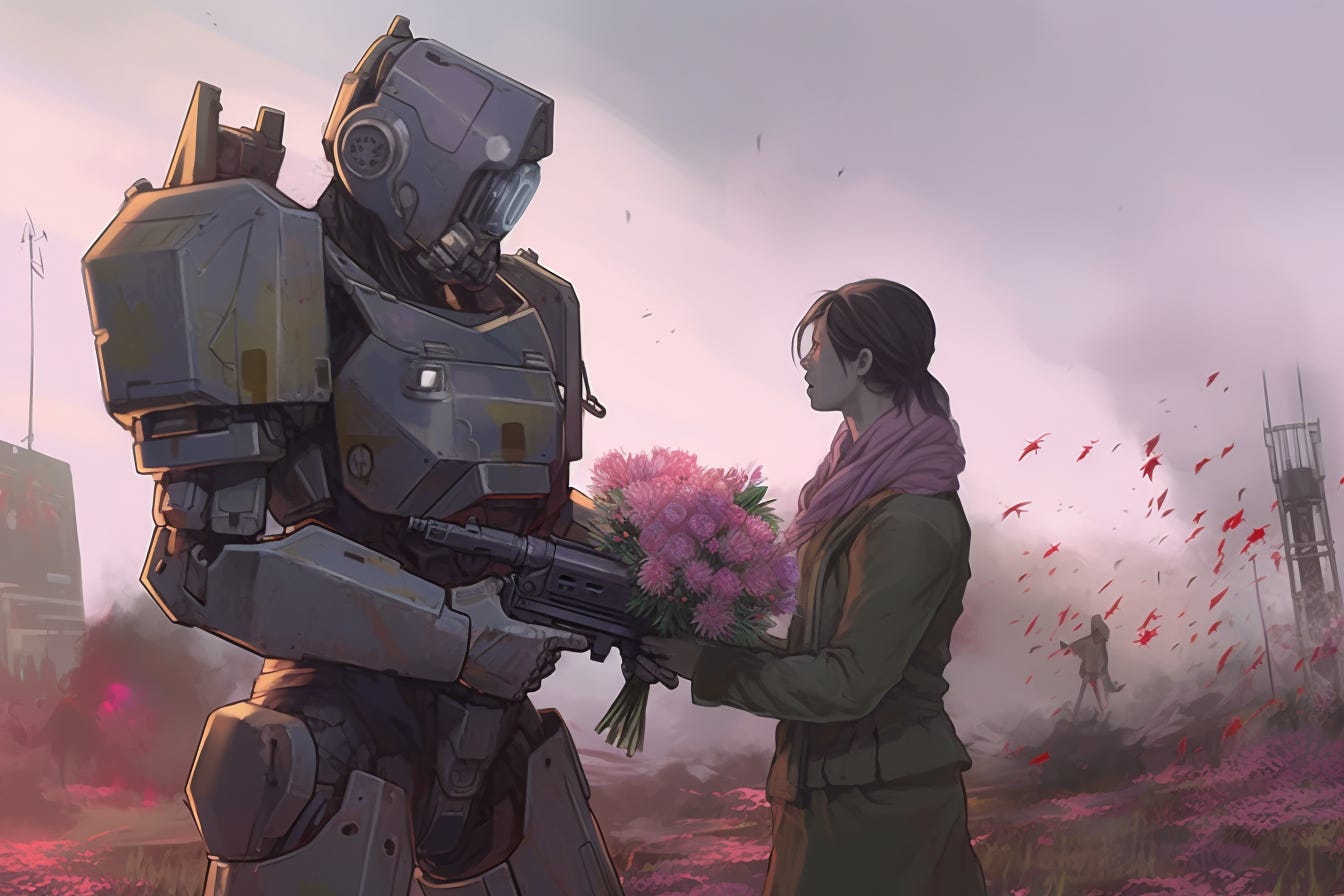

It's very hard to predict, especially the future, but I am going to go out on a limb and say knowledge work of every kind: academia, lawyering, software programming etc are going to be dramatically transformed. I am not saying they will be replaced. A better analogy - given we have already mentioned the conquering 'hero' Robert Clive, is how warfare has changed. A few hundred years ago, this is what it looked like to be on a battlefield:

Robert Clive would have had a gun, but otherwise the Battle of Plassey would have looked a lot like the picture above. Robert Clive was a nasty man, but he was good at killing people and back in those days, mastery of the art of killing got you a governor-generalship. I don't mean giving orders to kill, but the actual direct ability to take a weapon and stab or shoot someone. Warriors were a bit like movie stars and major athletes - admired for their abilities and charisma even if their personal qualities were less than appealing. Can you imagine that today?

That's because the same battlefield might look a little like:

It doesn't matter how good you are with a spear or a gun: a fleet of B52's is going to take you out like you were a pebble at the bottom of a shoe. War hasn't ended (far from it!) but victory is not a consequence of personal heroics. Militaries are systems - perhaps the most prominent systems of the modern era - and the better system wins.

I think that's the future of knowledge work - today's intellectual climate still celebrates (and hires) the star - the great thinker or writer or scientist. My gut says the days of the intellectual superstar are over. We will need to create systems of knowledge, with the creative lead playing the role of a director more than an individual contributor.

How to be a better doomsdayer

Talking about systems, it's impossible to speak about AI for more than a few minutes before someone mentions a doomsday scenario. NGL, I tick many of the boxes. Making up scenarios in which AI will wipe out humanity: check. Watched/read too much Sci-Fi: check. Trolling for dollars: not yet, need to build my email list first.

Here's my shtick: if you want to doom, be a real doomer. Real doomers don't stick to one apocalypse; they multiply their catastrophes.

Our robotic overlords are merely the latest in a series of doomsday technologies that started with nuclear weapons. Remember the 'Day After'?

We still haven't solved the nuclear crisis, but it's mostly receded from our minds though the war between Russia and Ukraine as revived those fears. The reigning apocalyptic scenario is climate collapse, of a planet rendered uninhabitable because of runaway warming. We have definitely not solved that crisis.

These three crises are related!

Without the Cold War, AI would have never been developed the way it did - computers are the material manifestation of the social and geopolitical systems that arose to manufacture bombs, missiles and generally manage cold war competition. And we wouldn't have created a science of climate change if we didn't have the sensor networks and computational resources. Paul Edwards has written eloquently about these interrelationships. But the person who truly bit the proverbial bullet was Herman Kahn, rumored to be the inspiration behind Dr. Strangelove:

Herman Kahn wrote a fantastic book called "On Thermonuclear War," fantastic not just because of its quality, but also because of the calm with which it approached its apocalyptic topic. The cold war got us used to planetary risk, but the institutions it spawned were niche institutions, designed for adversarial war against an identifiable enemy and not for collaborative labor to counter developments that will affect every one of us everyday. But its treaty frameworks, international institutions and crisscrossing networks of information and energy are what we have as the starting point for future systems that govern the earth.

If we want to be good doomsdayers, we need to think the unthinkable with Kahn and others who saw the systemic nature of the nuclear problem and the systemic nature of the solution. Of course, we live in a much more complex system than cold warriors did in the fifties so our imaginations will have to be much more wicked.