Kyborg 23: SOS7

Today’s update is the first that starts to look beyond Taylor’s exploration of the modern Self and its formation. Yes, it’s the self that’s colonized the world - both with its hard power and its soft power - but that doesn’t mean other types of self hood aren’t possible. In any case, as we reach the limits of this modern self - it’s fragmenting and even collapsing due to external (climate change) as well as internal (surveillance and computing) contradictions, we need to ask:

How else could it be? What might it be to inhabit a different self?

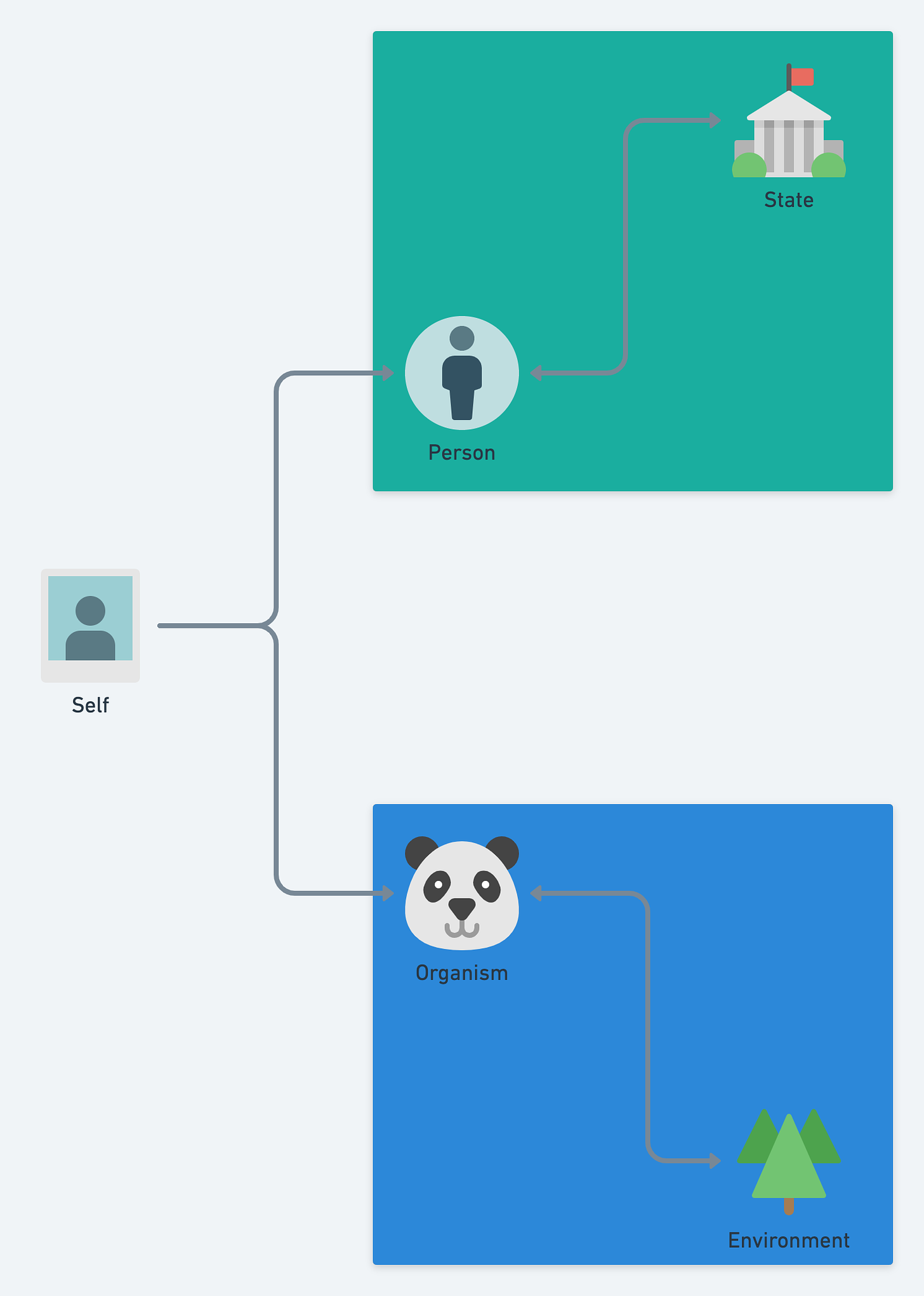

That brings me to the nature-society divide, for the self that Taylor has recounted lives firmly on one side of it, namely: society. The Taylorian self is a personal and a social phenomenon, i.e., either how it’s experienced by me as an individual or how it manifests in the social world, i.e., social ideas about autonomy, freedom etc and how they are protected or violated by institutions such as the state. In this, the self is primarily represented as a person, and the person is surrounded by society and its institutions such as the state.

That’s the Person-Society dialectic.

At the outer limits of this autonomous self-society is Niklas Luhmann’s treatment of an autonomous social being that he simply terms SOCIETY - to denote the single world spanning social being encompassing all human beings and fully autonomous of all other beings on this planet.

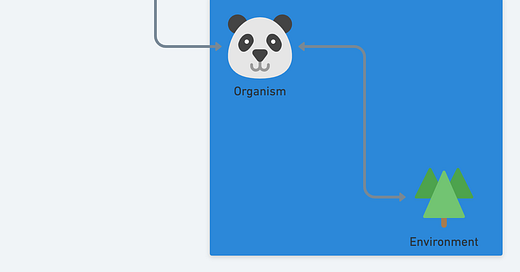

But there’s another approach to the self which is more biological, of treating the self as an organism and the organism’s surround as its environment. That biological self intrudes itself into society primarily as pathology, of the outcome of mental illness or brain injury. Consider the phenomenon known as Capgras Syndrome, in which:

Capgras delusion is a psychiatric disorder in which a person holds a delusion that a friend, spouse, parent, or other close family member (or pet) has been replaced by an identical impostor. It is named after Joseph Capgras (1873–1950), a French psychiatrist.

Or other syndromes in which people have a violent reaction to one of their limbs, believing that it’s an alien object attached to their bodies. The bodily self and its pathologies opens a window into an animal world.

That biological self also starts with an autonomous being who shapes and is shaped by the world that the being inhabits. But the similarities stop soon, for the division between nature and society is the basic division of modernity and the way a person inhabits society is quintessentially human, while the way animals inhabit their environment is of another, ‘natural’ order.

Perhaps even more importantly, the way social scientists and humanists are trained and how they communicate their work is quite different from the way natural scientists are trained and how they communicate their work.

What conceptual method might help us look beyond these disciplinary boundaries?

One candidate: phenomenology

The tradition of philosophical inquiry that starts with Husserl has been embraced by many scientists as the best method to incorporate the first, second and third person approaches to mind, cognition and self. In particular, the French phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty is a major inspiration for scholars who see the body as the key to a future science of the self that’s both natural science and social science.

I am skeptical of the phenomenological approach’s power for reasons I will explain later this week.

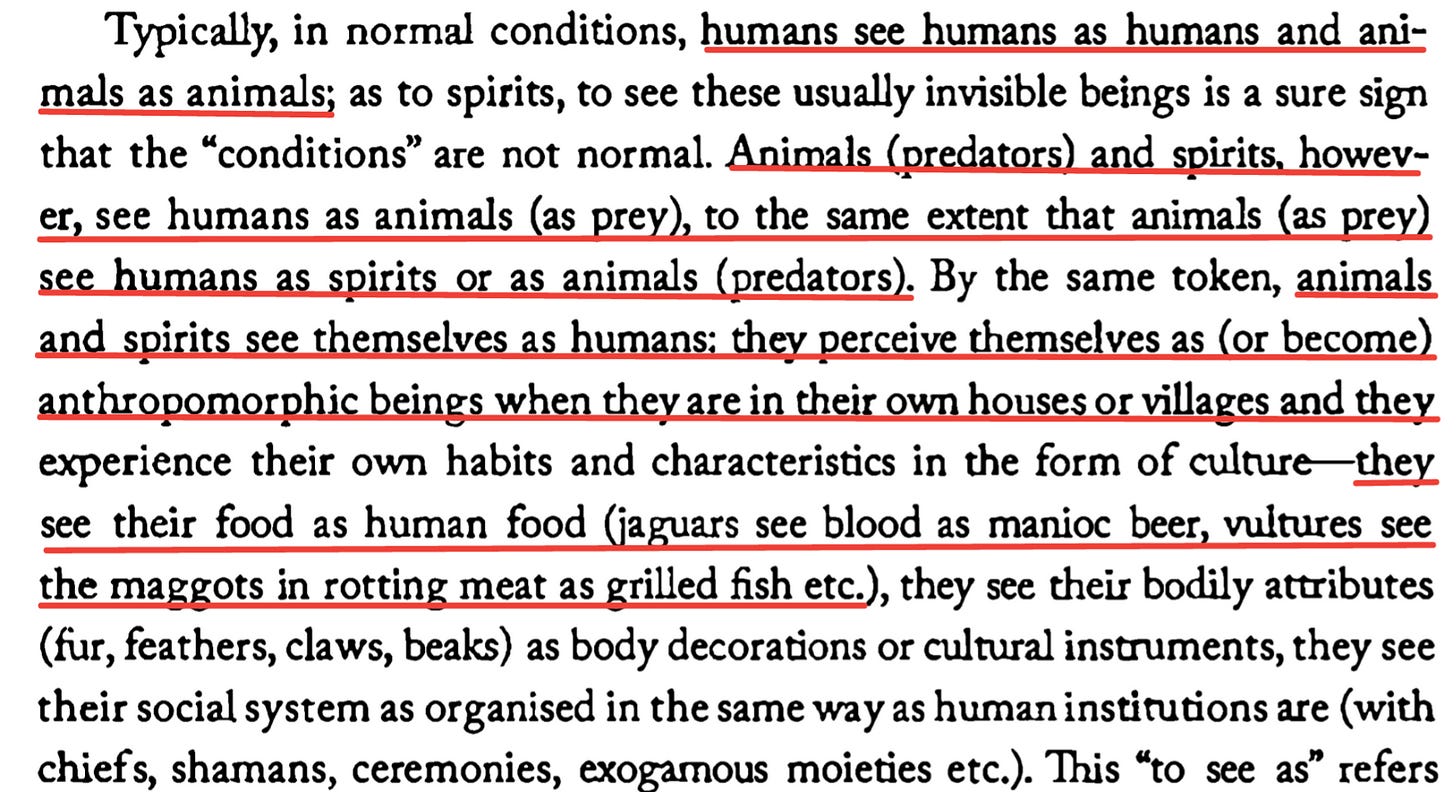

If phenomenology doesn’t work, where do we go for inspiration? One place to start is with cultures that have a very different perspective on how to carve reality. The Brazilian anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro for example:

EVDC says:

The most brilliant insight here is not that animals and humans view the world from their own perspective - which would be a multispecies take on the ancient tale of the seven blind men and the elephant - but that that different species have the same perspective on multiple worlds. Or as EVDC says:

If we continue to wear the modernist hat, we’ll say the Amerindian naturalizes the social or socializes the natural, but neither does justice to this ontological insight. Whether true or false, it offers the possibility that ontology is way more flexible than we normally take it to be and in fact, the project of phenomenology as fundamental ontology (Heidegger’s take on Husserl) is inadequate for what we need to do.

Let’s keep all these proliferating worlds and views in mind as we read Taylor for three more days