Linear and Nonlinear Karma

Thoughtlets

I am shifting gears in this newsletter; at least for a bit. Instead of theoretical reflections, I am going to share ‘thoughtlets.’ Obvious question:

What’s a thoughtlet?

A thoughtlet is a mental signpost - it points you in roughly the right direction but it’s far from being a map, let alone an accurate representation of the world. Imagine hiking on an unfamiliar trail. Say it’s getting dark and you’re a little worried that you might be lost. And then you see a cairn:

What a relief right? At least you’re not lost. A thoughtlet is a mental version of a cairn: a signpost that says you’re not lost. A thoughtlet can be a mental model, a heuristic, a hunch, a promising piece of evidence.

Today’s thoughtlet is about the relationship between actions and their consequences: let’s call them linear and nonlinear karma.

Linear and Nonlinear Karma

Linear karma is when actions have expected consequences. You rob a bank; the police catch you; you go to jail. Expectation meets reality. Nonlinear karma is when actions have unexpected consequences: you rob a bank, the bank is owned by a hated billionaire who prevents the masses from withdrawing their funds, the people revolt, the revolt spreads and before you know it, a revolution unfolds and the robbers are the new rulers.

Incidentally, Stalin was a bank robber - it was a revenue stream for the then struggling communist party.

One of my favorite mental models of nonlinear karma is Jevons’ paradox. William Stanley Jevons (a name like that is waiting for the eponymous paradox) noticed that as it became more efficient to mine coal and more coal entered into the market, the price of coal became more expensive rather than becoming cheaper as one might expect from the law of supply and demand (which is linear karma of course).

The reason is easy to understand once its stated: as the supply of coal increased more reliably, more people started using coal as a source of energy and so demand increased much faster than supply - the nonlinearity - and as a result the price of coal went up. Nonlinearities arise in technological and economic systems because new technologies makes possible products (and demands for those products) that were impossible or even unimaginable before. We wouldn’t have taxis on demand - Uber and Ola - without a smartphone.

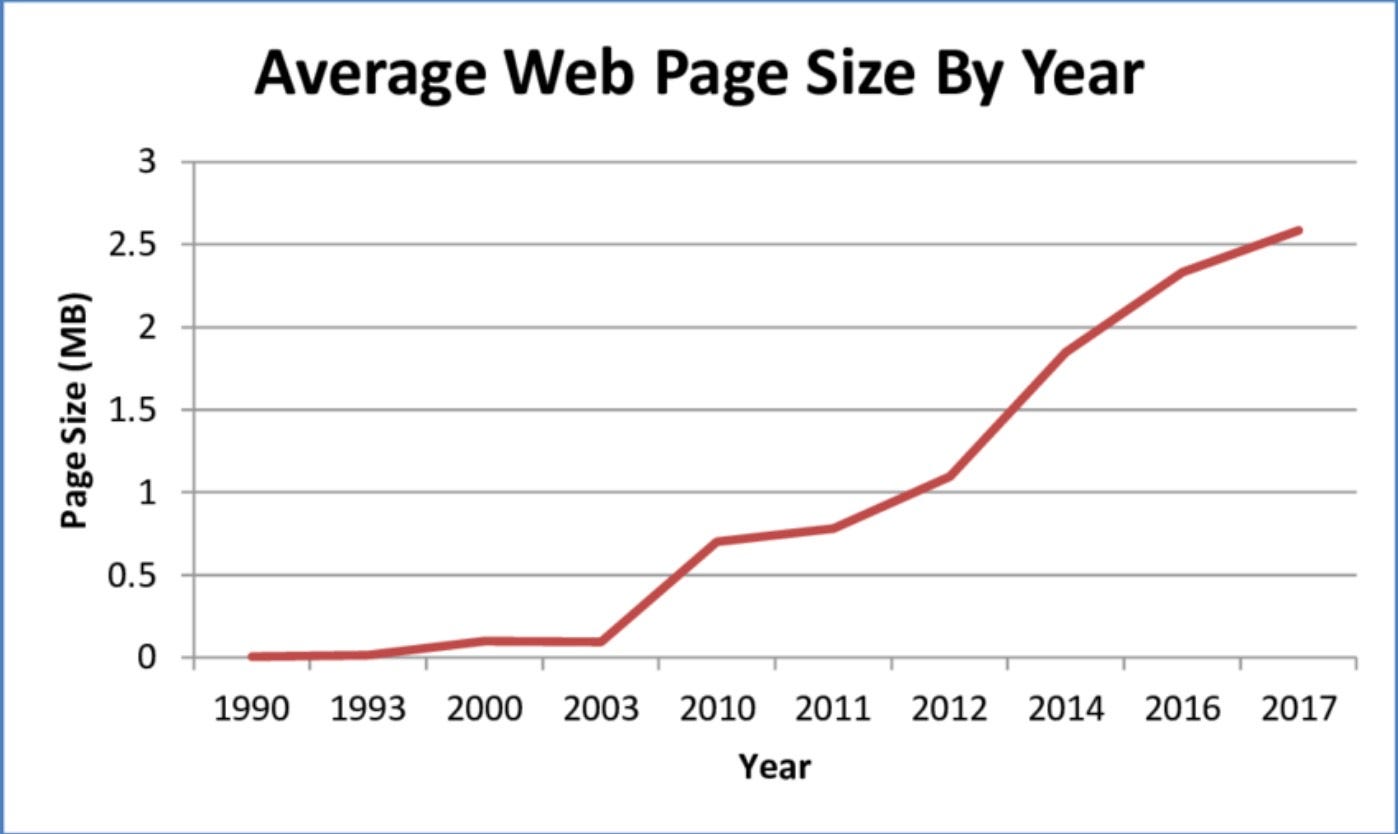

Another example: websites are almost as slow today as they were twenty years ago despite dramatic improvements in web technologies. But that’s because websites have gone from a few lines of HTML to video and image driven web apps with Javascript and tracking thrown in for good measure.

In a meta-Jevon’s paradox, sometimes the price of a commodity hasn’t risen even when you think it has, or at least not according to a plausible measure of price. For example, many people complain about how Lego prices are going through the roof - you can now spend five hundred dollars or more for a fancy set. The paradox here is that unit price (price/lego piece) has gone down or stayed constant but Lego is now selling more complex sets with many more pieces than it used to.

The reason, again, is simple once you think about it: most people played with their first Lego set when they were children and their expectations of a set were low. But the same person when buying a Lego set as an adult wants a richer experience: they want to make Death Stars rather than Battle Cruisers.

In other words, Lego has been able to capitalize on adult nostalgia for a favorite childhood toy combined with the need for creative play at all ages. Wouldn’t have happened if Lego hadn’t created a high quality mix and match toy for kids.

Platforms Cause Nonlinearity

In all of the above cases: banks, smartphones, coal, lego, the underlying cause of the nonlinearity is infrastructure. Or a platform. Or a medium. Which is to say, a technology that makes other technologies possible. Smartphones, energy sources and toy bricks are all enablers, making it possible for users to imagine new applications and artifacts they couldn’t have imagined in the absence of the platform.

Nonlinearity is a direct consequence of the enabling function of infrastructure and platforms.

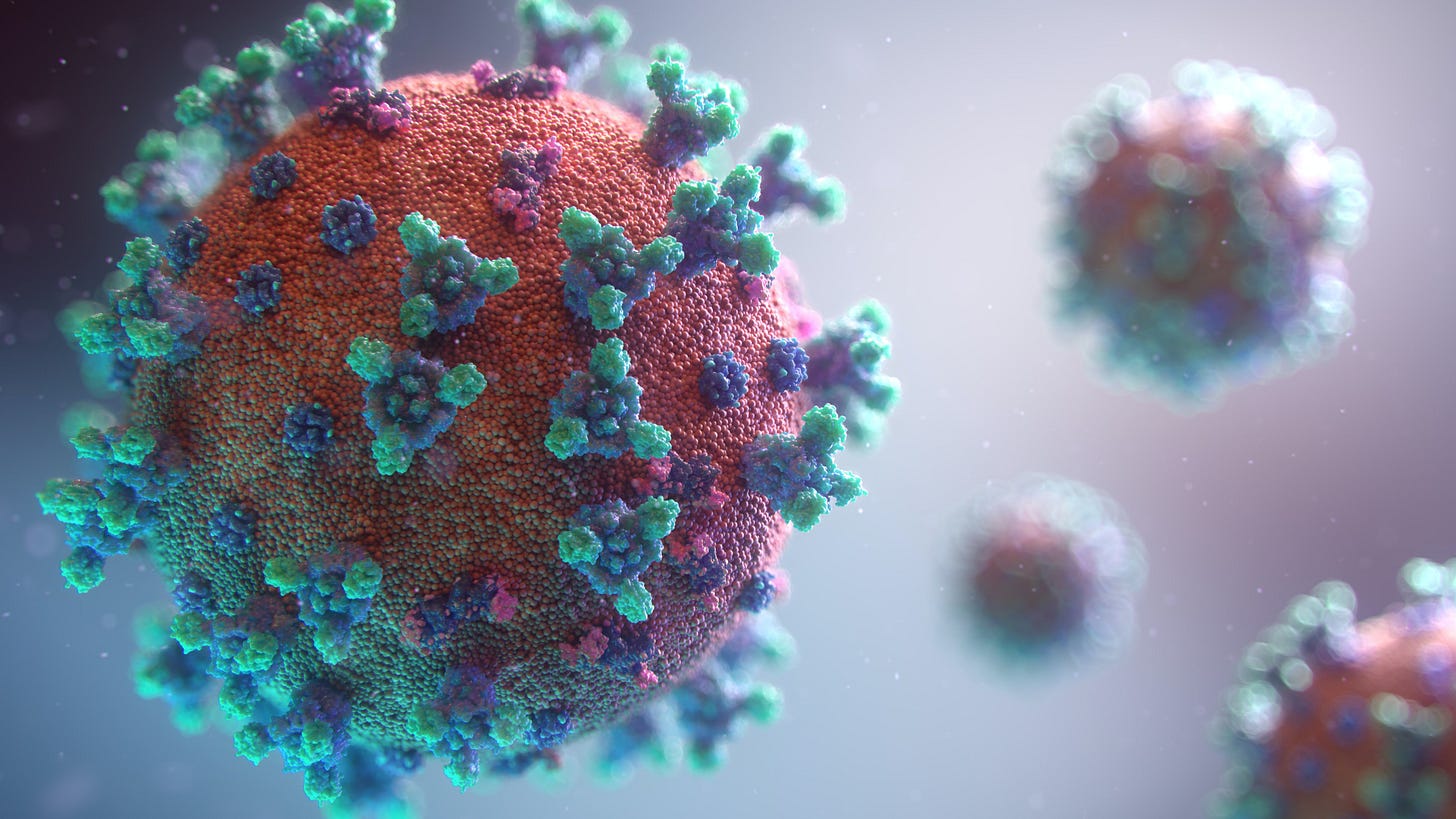

You know what else causes nonlinearity? Plagues, pandemics and climate change. For the same reason. A disease that affects everybody everywhere changes the rules for ever. Climate change destroys civilizations. We take the air and water for granted but you bet you’re going to notice when all the wells are poisoned and the air is too hot to breathe.

Air and water are infrastructure too.

The Future is Hard to Predict

The plague of Justinian hit the Eastern Roman Empire hard, killing over 20% of the population of the imperial capital, Constantinople and about a 100 million people across Eurasia. Here comes the interesting part, where Sabbatini et. al. write:

The epidemic plague significantly contributed to the weakening of the Eastern Roman Empire, and the rapid decline of the Persian Empire, while during the early expansion phases of Islam, it indirectly favoured the nomadic Arab tribes which, moving on desert or semi-desert territories, succeeded in escaping the contagion more easily.

It’s impossible to tell whether the plague was a key factor in weakening the Byzantine and the Persian empires, but it’s one answer to a puzzling question: how did early Islam conquer two major civilizations in such a short period of time?

The unfortunate thing about nonlinear karma is the difficulty of prediction - it’s hard enough to pinpoint nonlinear effects in the past, let alone the future!

We don’t know what’s going to happen with the COVID crisis. Will the relative success of China in curbing the disease and the apparent failure of the US to do so (at the time of writing) lead to a shift away from belief in the western model of democracy versus a one party state?

Or will it lead to the exact opposite: will western countries and their allies lash out against China in their anger about the origins of the corona virus?

More universally: will the massive increase in state power, surveillance and general intrusion become a permanent affair? Will 2020 bookend 9/11 as watersheds in the history of democratic governance?

The answer is: we don’t know for sure but it’s time to read the tea-leaves more carefully.