Looking at the Climate Aslant

What is the mark of the mental?

If you’re to believe the phenomenologists, that mark is ‘intentionality,’ or aboutness, i.e., the property of mental acts, events and states to be about other things. The word CAT is about cats, the SMELL of a rose is about roses and so on.

Out of that insight came a profound philosophical tradition. However, aboutness sets the mind against the world - the mind is over here, that which it’s about is over there. What if we started with a different mark: let’s call it ‘withness’ that the mark of the mental is an expression of solidarity with the world, that every mental state is an expression of the ties that bind us to other beings.

It’s fantastic (perhaps a great romantic lie) that every word we speak is an expression of solidarity, but what makes that solidarity possible? What are its preconditions? In answering that question, I want to switch philosophical traditions and offer an Indian concept: ‘bandhan’ (bandh = bound, being tied to something). We are able to offer solidarity precisely because we are intrinsically bound to other beings, and a recognition of that condition (of being bound) is the mark of the mental.

What tradition might we be able to erect on top of withness and bandhan, the ties that bind us to others?

Once we recognize these ties as fundamental, every being on this planet becomes a fellow traveler. I am not saying we have to love all our fellows - some are horrible and others are embarrassing, but they are all fellows. That mutual recognition is crucial, and is there when the lion and the antelope spot each other on the hunting ground (cue great romantic lie).

And now, I will jump to something totally unrelated. But keep those ties in your pocket.

I read somewhere that the modern environmental movement started in the United States soon after the second world war. I knew this truth before I read about it, but I didn’t recognize its importance until now. Between Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and Nixon founding the EPA, it looked like the Liberal Leviathan was about to solve the environment just as it had solved fascism on D-Day and solved inequality with the New Deal.

And then it failed. LA smog was an easy battle, but the war against fossil fuels was won by Sauron. Carbon remains the one element that rules them all. Every progressive policy from Build Back Better to the Green New Deal is infused with this history of success and failure.

Climate Change was invented in the United States.

No, I am not switching to the dark side, but the framing of climate change as CLIMATE CHANGE is a problem. Yeah, I know. It’s counter to everything I have believed and written for the last decade, but walk along as I explain how climate change is only a glimpse of the planet and perhaps not even the best vantage point.

Exhibit A: take the name of the best known US climate action organization: 350.org. As the name suggests, the fundamental problem is one of pollution, i.e., the amount of carbon dioxide and methane in the atmosphere. Responding to climate change amounts to one of two things:

Stopping activities that add carbon to the atmosphere and replacing them with clean counterparts. Switching your Mercedes for a Tesla will accomplish that goal assuming fossil fuels weren’t burnt in the process of making the Tesla.

Investing in mechanisms and technologies that remove carbon from the atmosphere, whether that means planting lots of trees (even if they’re monocultures) or geoengineering projects that remove carbon from the atmosphere via technological means.

If climate change is primarily a problem of unchecked pollution, the tragedy at its American core can be stated simply:

Why have we been unable to solve a technical problem when we have known about it for decades, when we have the technological ingenuity to offer alternatives and when we have the institutional capacity - both in government and the private sector - to offer a massive response?

In an alternate history, if the US had launched massive climate interventions after the fall of the Soviet Union and pushed for green capitalism worldwide, we would have truly reached the end of history. Why didn’t the hegemon articulate and impose a planetary form of imperialism when it had the power and the legitimacy to do so?

Why do we not have the Climate Leviathan yet?

These are genuine puzzles, but if you look at the tragedy aslant, you might wonder:

Is this everyone’s tragedy or only America’s?

Wearing an Indian hat, it’s clear we will never ever be Tesla prosperous; it’s not like mobile telephony where Indians acquired cell phones without ever having landlines. Our failure isn’t that Indian institutions haven’t been able to stop carbon emissions (though they haven’t) — it’s that we haven’t been able to deliver any kind of prosperity or freedom to our citizens and it’s post carbon flourishing we need to imagine as a people - a much bigger problem that decarbonizing the current economy. But if we accept the pollution framing of climate change, the only two responses Indian decision makers can plausibly defend are:

Give us time to pollute our way to prosperity; after all we are still responsible for a very small amount.

Look how fast we are growing our solar grid. We will be carbon neutral before you are.

Neither of these explanations point out the failures of the Indian system, and in fact, decarbonization as a convenient global yardstick might be far more acceptable to Indian elites than engaging with the ecological and economic consequences of their hold on power.

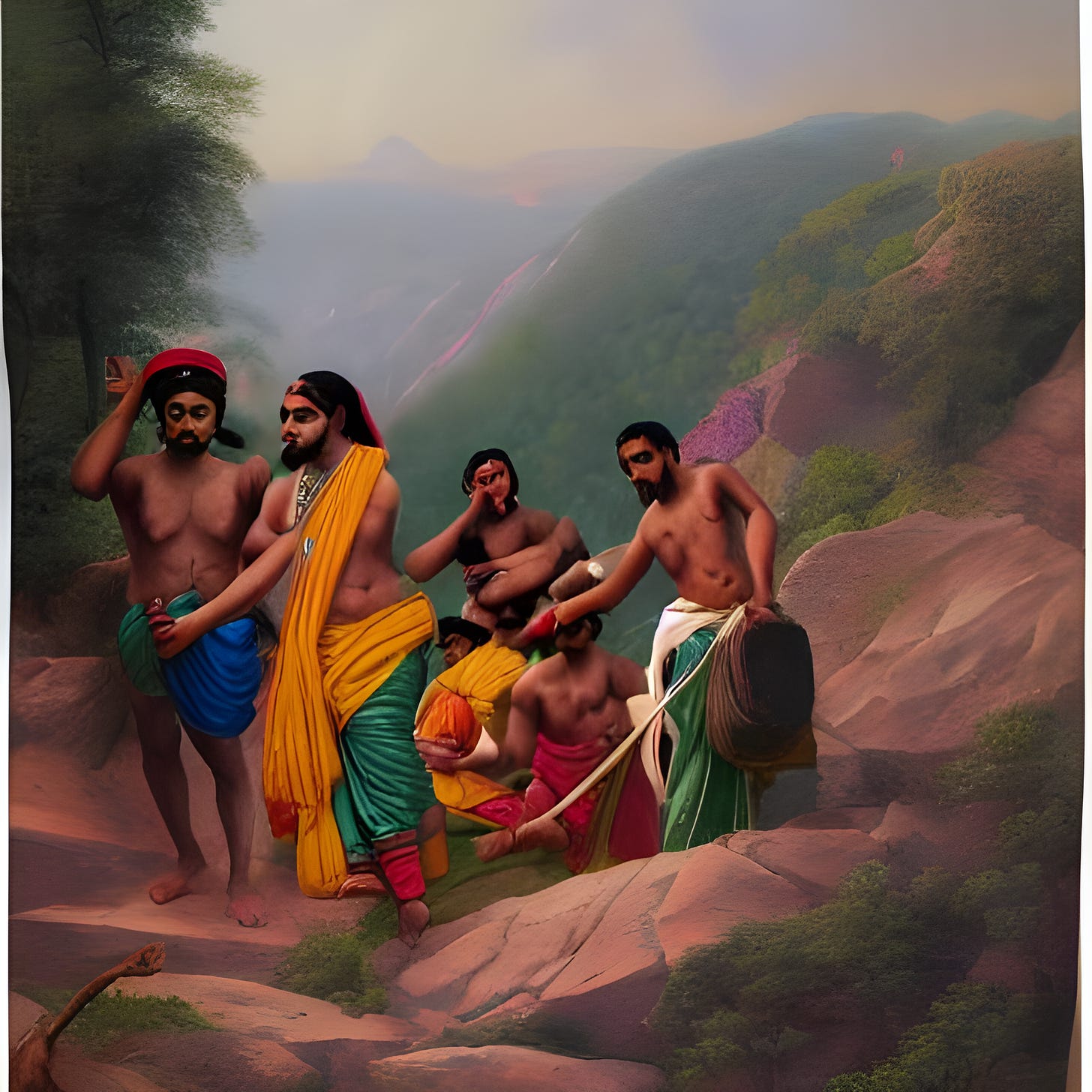

Let’s see if we can get a different glimpse of the earth by standing on top of Tagore and Gandhi’s shoulders.

Which is why it’s important to engage with visions of flourishing that don’t take the modern system and its imaginations as the only plausible futures. Indigenous cultures the world over offer alternatives. Afrofuturism offers an alternative. Here’s a book we should all read (I am adding it to the list of books I will be discussing in this newsletter):

What I find interesting about the Indian independence struggle is that it simultaneously engaged with alternatives to modernity while also creating modern institutions including the Indian nation state itself. But the hill we are climbing is steep. Seventy five years after independence, let’s have no illusions: that project of offering a civilizational alternative to the Liberal Leviathan is dead. But isn’t that sense of defeat what people must have felt in 1875, when the imperial power looked like it was invincible? Out of that despair arose a movement that finally overthrew the empire.