M17: Reality Media Part I

This week’s news

An interesting essay on how VR art might help us experience the world aslant, so to speak, from the perspective of other people or even other beings. I can’t be a whale in the real world, but I might be able to be one in VR. The downside of immersive media is the same as the upside: immersion obscures imagination.

Movies are already more constraining than novels and reality media will be even more constraining: you will only see and touch and hear what the reality creator wants you to see and touch and hear. As we move up the immersive ladder, we also increase the resource asymmetry between the creator and the consumer.

A novel reader is roughly equal: they too can pick up a pen and start writing, but it’s hard to create a scene in response to a movie and will be even harder to create a compelling VR experience: the affordances of reality media bias them towards the largest studios. Yes, there’s been an enormous increase in user created video and audio content, but most of these platforms (say YouTube or TikTok) are winner-take-all, with a few megastars and then everyone else. We are all ‘creators’ now but very few of us are CREATORS. Left to its devices reality media will make that ponzi scheme worse.

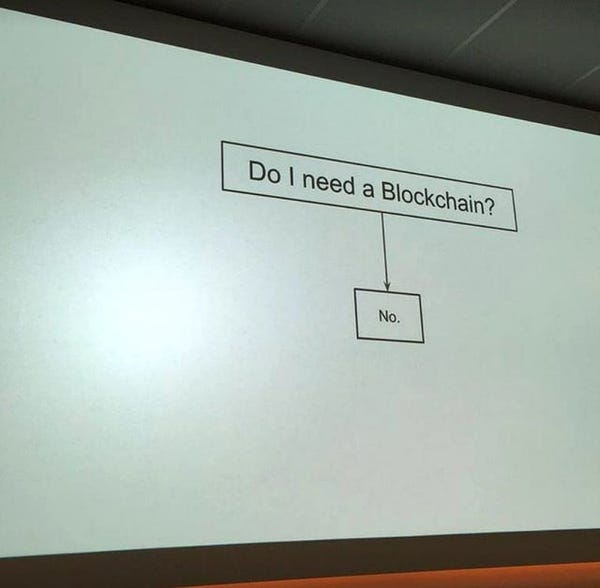

In other news, gamers hate NFTs with a vengeance even though transferable game properties are often touted as the reason for NFTs to exist. Casey Newton tries to explain why:

Some key points:

Reading through angry social media posts, a few key themes emerge. One, gamers and developers are engaged in a perennial battle over how games are monetized. Gamers generally want to pay one low price to play a game forever; developers are forever experimenting with exotic new financing schemes to grow their profits. Gamers have already been subjected to premium downloadable content; subscriptions, micro-transactions, and randomized loot boxes, each of which has been more poorly received than the last.

while the music industry has a different reception:

One, live entertainment has always done a healthy business in collectibles; gaming hasn’t. Lots of people buy T-shirts when they go to a concert; it stands to reason that some of them would pay for a unique digital item as well. Many NFTs are sold with the implicit promise that they are investments; projects like Legend’s or Coachella’s, on the other hand, can represent themselves more honestly as souvenirs.

In practice, some gamers do buy souvenirs from the games they play. But not as many as buy concert T-shirts. And gamers’ souvenirs, whether posters or action figures, are separate from the game itself, and have no bearing on how fun the game is to play. That seems important.

It’s foolish to think that a disruptive technology will steamroll across all industries at once. Progress (or is it regress - see tweet below 😁) will proceed in fits and starts and there’s no reason to think breakthrough applications will start where we think they will or even whether the original platforms (say, bitcoin) or even currencies per se will be their mature form.

David Chalmers has a new book called ‘Reality +’ on the new reality technologies, but if you don’t want to read a doorstop, here’s an interview with the philosopher from a couple of years ago. Chalmers coined the phrase ‘the hard problem of consciousness’ and was one of the key thinkers in making consciousness studies a respectable topic of investigation, but in the last thirty years, the problem of consciousness has slowly but steadily shifted away from being a philosophical problem to becoming a scientific discipline. Not because the philosophical challenges have gone away, but because science can (perhaps) make progress after setting the hard problems aside. Anil Seth’s relatively new book on consciousness presents the scientific case from what’s perhaps the dominant framework.

This Week’s Theme

I gave away the surprise if you were reading carefully: David Chalmers’ shift away from consciousness to reality+ is one sign among many that a new domain of investigation is opening up. The ‘question of reality’ might be ripe for intense inquiry. After all, what’s the very hardest problem of them all?

Why is there something instead of nothing?

I might call that the ‘hard problem of existence.’ It’s a terribly puzzling question, for one the one hand you come to it with the assurance that you exist, so you know it in your bones, but on the other hand, what could be the alternative? Nothing? It’s impossible to ask the question of existence from outside the fold, for only beings who exist can puzzle about it. There’s no distance between the poser of the question and the object of their investigation.

Even God (if they exist) can’t ask the question of existence from the outside, for they too exist (if they do!), so even omniscience and omnipotence can’t solve the problem of existence. Or as the Rig Veda says in the Nasadiya Sukta:

Who really knows? Who shall here proclaim it?—from where was it born, from where this creation? The gods are on this side of the creation of this (world). So then who does know from where it came to be?

We are all on this shore of the ocean of existence, so how can we talk about it as if it were a distant object of contemplation? And what kind of knowledge can we come to possess of this supreme mystery?

The hunch is that reality media might help move the needle on the hard question of existence- if not the absolute question of ‘why is there anything at all?’ at least the relative question of ‘why is it this way and not that.’ This second question isn’t quite right either, but it’s the first step towards asking answerable questions. We will likely find interesting answers somewhere at the intersection of consciousness studies, a yet to exist ‘reality studies’ and newly invented reality media technologies.

A worthwhile goal: find a question about ‘reality’:

Answerable in the near future (~ 3 decades) &

Attempts at answering will have side benefits even if the original question is left by the wayside

An example of such a question from 70 years ago: can machines be intelligent? can machines be conscious? There was enormous debate about these questions through the nineties but the noise has settled down with the massive growth in AI, and the big problems have been broken down into smaller, more achievable goals.

It’s tempting to start with doable problems, but I believe the ‘great questions’ deserve to be stated audaciously before we chip off small pieces - we wouldn’t have made the progress we did if the big questions weren’t asked at the beginning. If engineering delivers usable products, design imagines products that can be used. At the early stages of a new domain of inquiry, we need designerly sensibility in spades.

I believe the question of reality is at the stage today that AI was in 1950 and consciousness studies in 1995. It needs powerful questions as much as powerful technologies and their marriage can take us into worlds we have never gone before. Question Design is an important skill at this stage.

We won’t address these questions by being parochial, by saying that every question worth answering will be answered by neuroscience or VR. We will have to cast our net wide: everything from the anthropology of indigenous knowledge traditions (for example, Eduardo Kohn’s “How Forests Think”) to the Meinongian logic of non-existent objects (I find Richard Routley and Graham Priest’s work fascinating).

Here’s a puzzle: is existence a real predicate? Which is to say: when I claim ‘so and so did so and so’ am I always presupposing that so and so exists or is there a meaningful sense in which ‘so and so did so and so AND so and so exists’ adds information? Clearly, it makes sense to say ‘Sherlock Holmes tussled with James Moriarty’ but neither of them existed. Yeah, but so what: humans talk about fictional objects as if they were real ones.

Is there a deeper sense in which non-existent objects are ‘real’?

Well, first of all, we have to expand our list of non-existent objects beyond fiction. Dreams reveal non-existent objects too, though there are traditions that attribute full blown reality to dream objects. Near-death experiences are even more problematic, and point to the boundary experience of death which is hard to say much about, but poses a question that’s beset people for ages: is there existence after death? There are also the mystical experiences of divinity and other contemplative states that were frequent in the premodern era. Reality media may make such experiences common place.

Are we turning full circle to a view of existence that was common before the scientific revolution? Metaphysics was the ‘first science,’ the science of being qua being, that was paired with Theology, the science of the One Being, i.e., God. Or back in India/East Asia, the philosophies of existence - both Hindu and Buddhist - were paired with contemplative practices.

The first science had both a subject and an object that felt natural to the people of those periods; perhaps reality media will expand and/or replace meditation traditions and revive the first science. The question of existence has been central to ‘the first science’ ever since Aristotle, but today concepts such as ‘reality’ and ‘existence’ are increasingly embedded in market decisions and in governance. ‘Existential Risk’ is a thing. What was traditionally divided between theology and philosophy and then became pure philosophy is now at the cusp of exploding into everyday life.

How much would you be willing to pay to insure yourself (your family/your nation/your planet) against existential risk. And if (when?) the apocalypse happens, who would you go to collect your payout?

PS: Insuring the planet reminds me that money is also a reality medium and I will cover it as such.

Whether it will be souped up meditation or something new altogether, reality media promises to multiply questions of existence many fold, making issues that are discussed in arcane precincts of analytical philosophy or passed from master to disciple in contemplative lineages into the ambit of a science that’s yet to exist.