M18: Reality Media Part II

What is reality media? The most common answer is descriptive, i.e., reality media is what already goes under that name, i.e., VR, AR and XR more generally. But why those and not others? Couple of weeks ago, we learned that cities are media too. If cities are media, what kind of media could they be? They would be reality media right?

There are good reasons to not stay with the industry definitions of reality media. I prefer to use the term ‘reality media’ not as a descriptor of technologies but of experiences: how does that medium make you feel? If it makes you feel engaged and immersed, it’s a reality medium. A novel makes text into a reality medium while a scientific tract isn’t. And of course cities are reality media because you have no choice but to be surrounded by them and immersed in them.

Ironically, it’s the disengagement from urban life that COVID forced upon us that created a demand for online connection which is being promised by the XR kind of reality media.

Designing for Trust

From 30,000 feet, the metaverse appears to be a river with two tributaries:

One tributary showcases technological progress,i.e., the evolution of the immersive internet (Web 1: Text; Web 2: Screens; Web 3: 3D).

Another tributary showcases the evolution of human experience and that of our economic and social institutions: from buying books online to riding an Uber to riding an autonomous vehicle

The technological perspective on the metaverse is the dominant story: what is VR? How can we make it more immersive? Or if you are a technological humanist, you might ask: how can we make VR more inclusive?

But in the background is an ongoing question about the human needs (if any) that VR is addressing, and inevitably, the problems created by an ‘always on’ matrix. Think about social media: a decade ago, everyone was writing blogs about the technology but now that social media saturation is reality, the vast majority of coverage is about the impact of social media on our minds, our politics and our sanity. So let me ask repose that question:

What are we designing the Interverse for?

I believe the answer is: Trust; the interverse is the latest in a long line of technologies of trust for without trust we can’t play the game of life, or as Frank says:

Strangers in the night

Exchanging glances

Wandering in the night

What were the chances

We'd be sharing love

Before the night was through?

What makes us dance? What makes us play?

Without risk it wouldn’t be fun and without trust it would be dangerous. Love needs trust. Trust and its cohort: risk, opportunity, security etc are what make the world go around. The city acts as both demand and supply for trust - demanding institutions that make it possible to live with strangers and supplying institutions that promote flourishing with strangers, and if the Interverse is the city writ large, it will demand and supply trust at a scale greater than any that’s come before.

I wrote about designing for trust a while ago, and while that was written in the context of COVID, most of what I said works for the metaverse as well:

Social media has increased the trust deficit and the metaverse will increase that deficit unless we do something about it - what could be worse than inhabiting a fake reality like the matrix?

Types of Trust

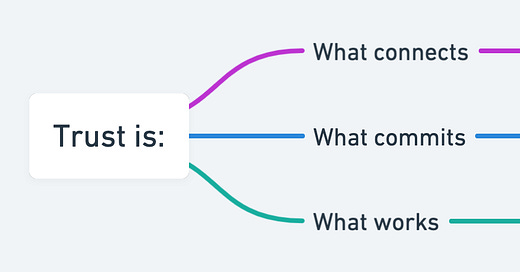

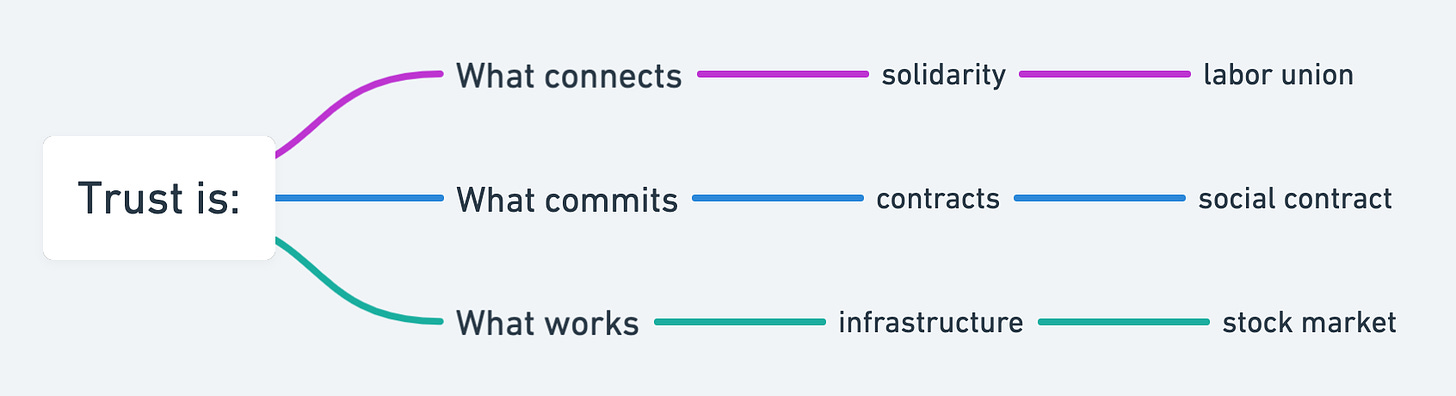

In our everyday language of trust, While our everyday use of the term is about interpersonal relations (‘is he trustworthy or not?’), it’s the social dimensions of trust that concern me, especially the institutions that embody social trust:

Trust is what connects us with others, e.g., making solidarity possible and institutionalized as a labor union.

Trust is what commits us to others, e.g., leading to social contracts and institutionalized as a constitution.

Trust is what works, e.g., social infrastructure, including risky infrastructure such as the stock market.

Another way of saying the same thing: there’s foreground trust and background trust. Foreground trust is what you notice, say, the used car salesman putting on his ‘trust me, this is a great car’ charm, but it’s background trust that’s more important: that we build cars that can last a decade without failure and yet we build an economy in which wealthier people trade in their cars every two years. Riding off a lot with a lemon is a foreground failure while GM and Chrysler getting an 80 billion dollar bailout is background failure.

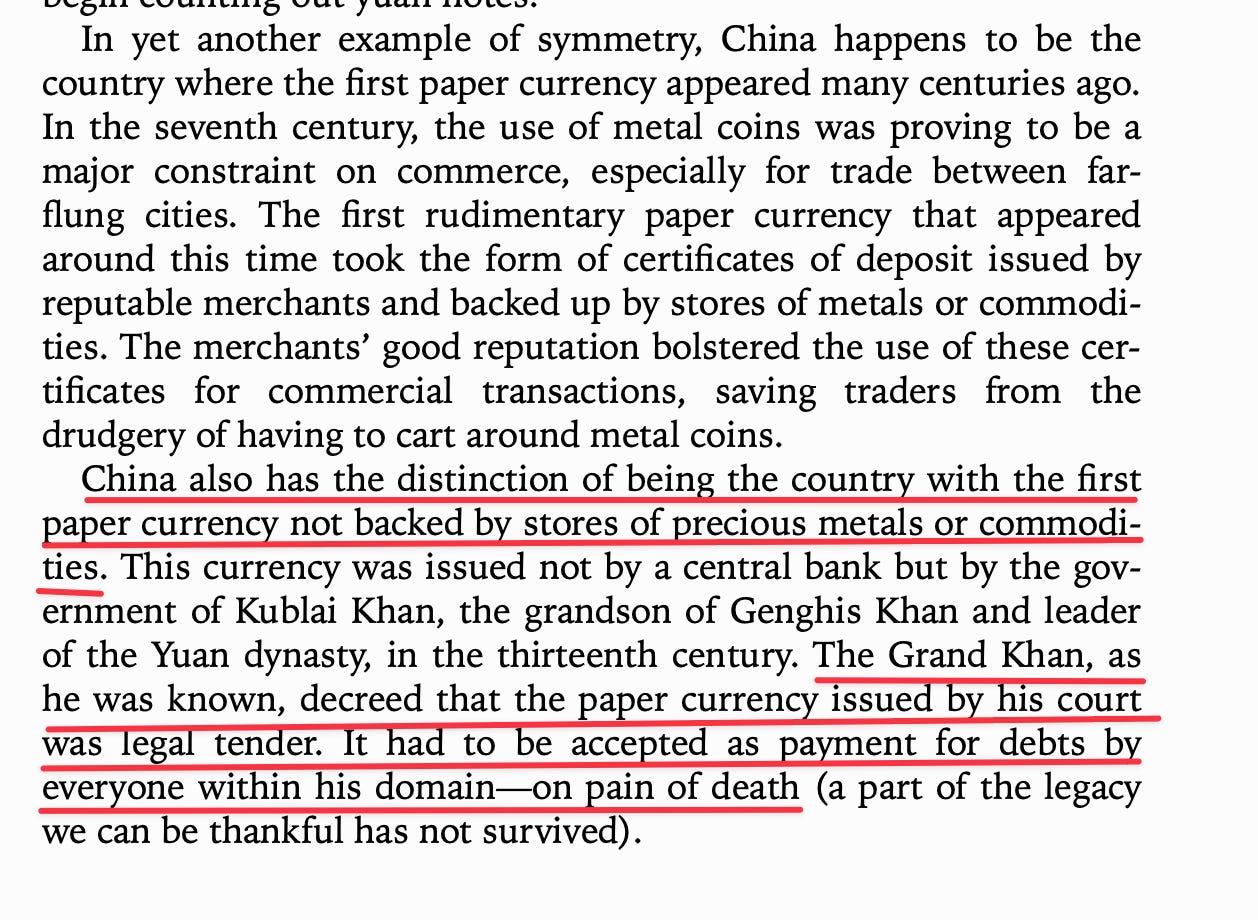

And while technological progress has certainly been adding up (just as it’s been doing in AI), it’s hard to imagine today’s furious interest in the metaverse without taking into account two background failures: the crash of 2008 and the pandemic of 2020-. Almost everyone I know feels the system has failed them even if we experience the failures in different ways. The large scale failure of the financial system in 2008 opened the door for alternative visions of money and banking, though there’s no reason to assume the alternatives on offer are the right ones. Just because crypto isn’t a centralized source of failure doesn’t mean it’s the right solution!

Similarly, the pandemic and working from home - no one I know will ever be returning to their physical offices five days a week - have totally changed the demand for connection online. That background failure of our financial system and our ways of working and learning are the ‘pain points’ that create demand for alternatives. Whether the interverse is the right response remains to be seen.

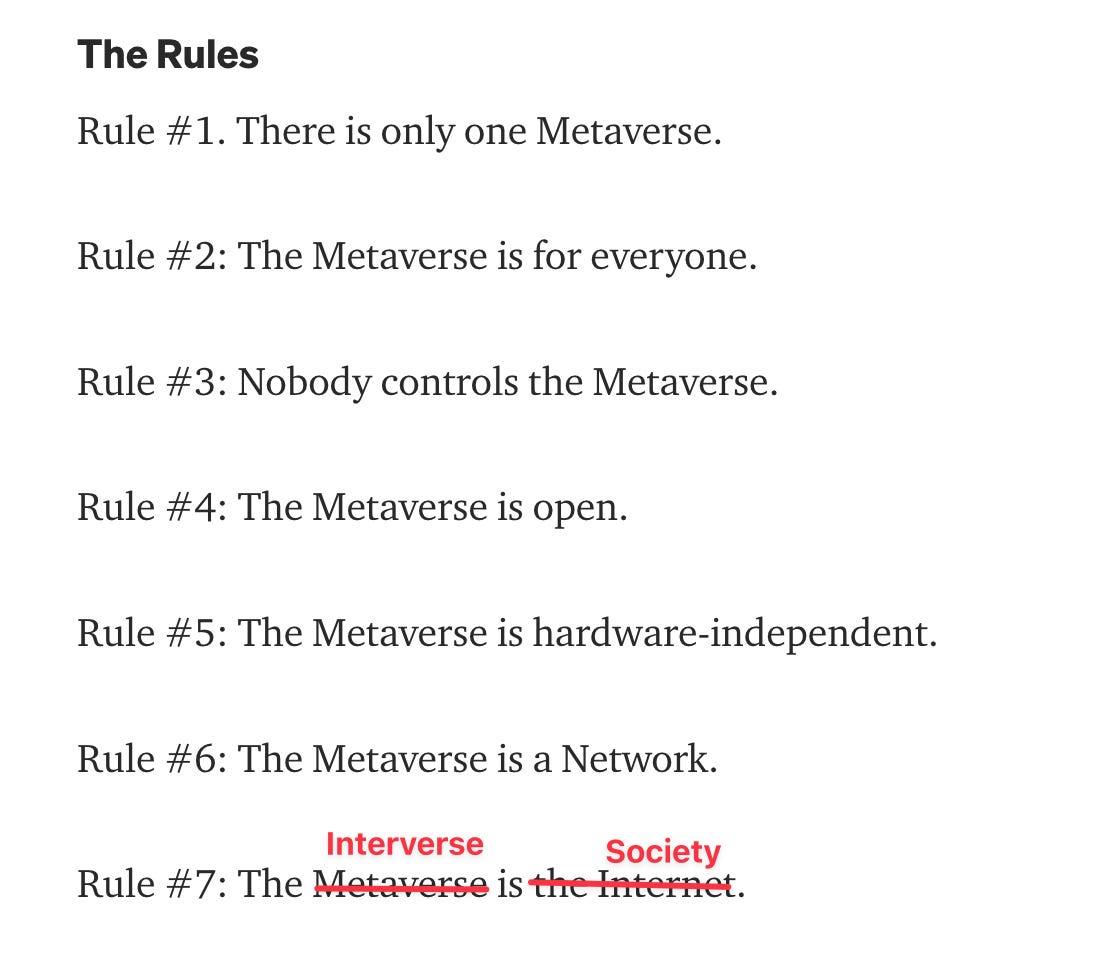

In “The Seven Rules of the Metaverse,” the VR pioneer Tony Parisi says: “The Metaverse is the Internet,” but if we take the failure of background trust as our starting point, we can also say: ‘the interverse is society.’ While social media drives fake news and alienation, a better way to understand what’s happening is that social media is both a cause and a symptom of system failure: it’s not an external entity that influences society for the worse, but one of the organs of that diseased society. Money is no different: it’s both a medium of trust and a cause of trust failure, and in the case of money the relationship between carrot and stick has been apparent from the beginning:

War ⇔ Money ⇔ War has been an equation for the very longest time and a major driver of imperial expansion as well as boom and bust cycles. So what happens when a new medium arises that claims to subsume both money and text?

How does reality media address our demand for trust, connection and belonging? Can it even do so?

and the flip side:

How will reality media prey upon our demand for trust, connection and belonging?