There will be no update next week. I usually write my essays a week in advance but commitments this week prevent me from doing so for the next one.

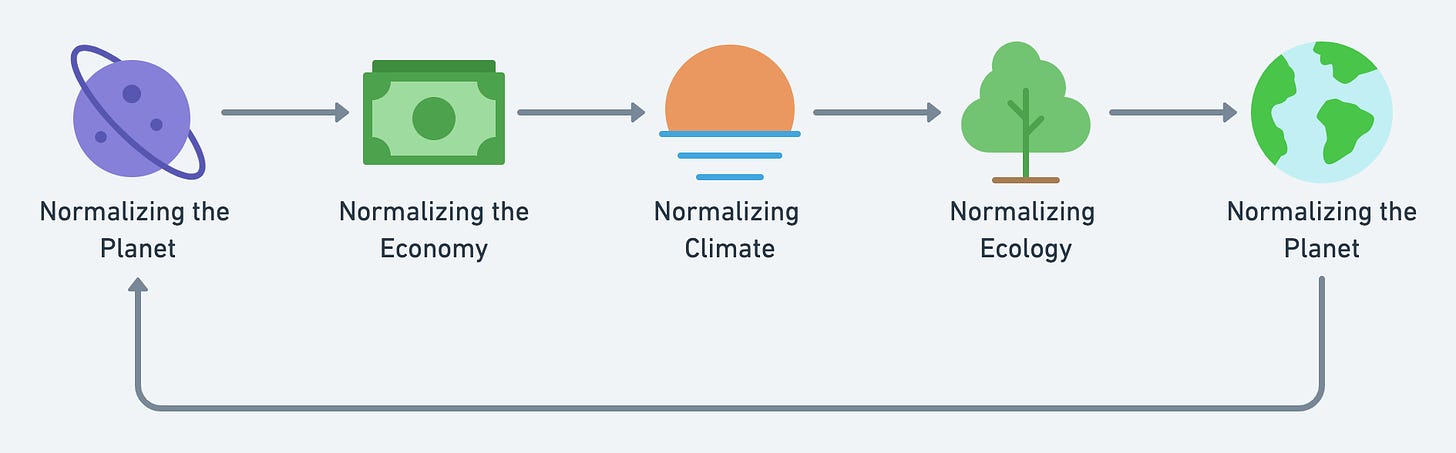

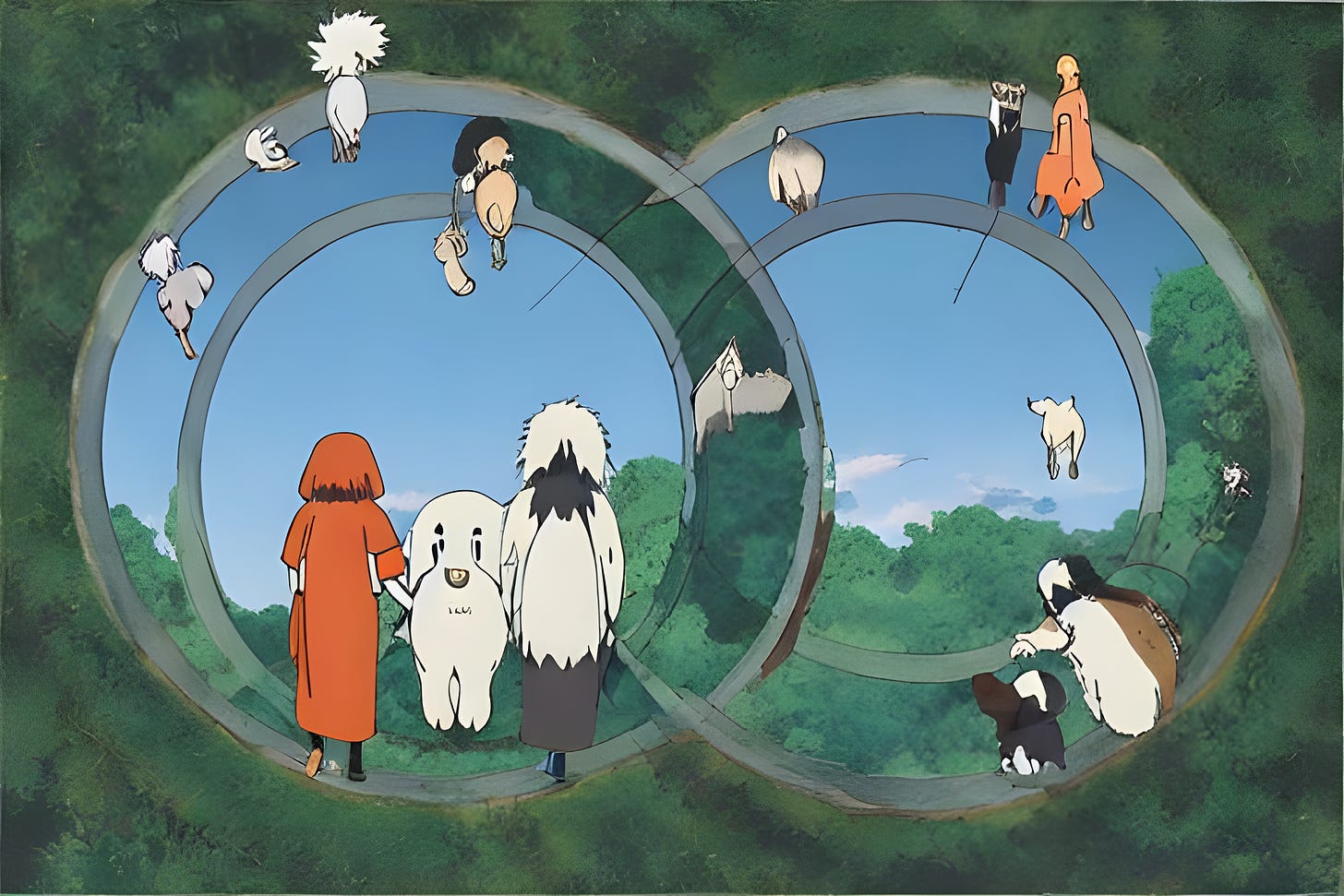

Today’s essay is the first in the ‘normalizing ecology’ series. The diagram above this paragraph explains the logic of this series, i.e., that normalizing the planet takes a series of steps:

Normalize the economy: that’s where we are today

Normalize climate: under way already

Normalize ecology: what I will be talking about for the next few essays

Normalize the planet: don’t know when or what this is going to be but we can speculate.

I mentioned the first two points - briefly - in my previous two essays. Hirschman played a big role in grasping the normalization of the capitalist system. But one musn’t forget Marx. In a recent article about KM, Branko Milanovic says:

His program was to propose an entirely new understanding of human history in which economic forces play an important, and perhaps, key role.

What else is this but the normalization of the economy as the primary engine of everyday life?

What will it take for the planet to play the same role at some time in the future? What new knowledge systems and institutions - comparable to the market, for example - do we need to set into motion for that to happen?

It’s not as if ‘ecology’ or its cognates such as ‘system’ and ‘network’ are new terms. They are immensely popular and pretty much every academic discipline you can imagine has a subdiscipline that has the word ‘system’ or ‘ecology’ in it. Like Systems Neuroscience or Political Ecology. Systems talk is everywhere.

What’s missing?

The n-gram of systems/networks/ecology gives us a clue. Systems is the winner by far and it peaked in the eighties. Our understanding of systems is still stuck in the Cold War, and the kind of systems Americans and the Soviets were building to win a nuclear arms race.

We need a new systems theory that isn’t dominated by physics or driven by motives bent on profit and war. But the heyday of systems during the Cold War also has a lesson to us: don’t conflate planet and ecology with climate change; our ecological crisis started in 1945, not 1995, and if we ‘solve’ the climate crisis via technology driven decarbonization the ecological crisis will morph into something else. That’s why the normalization of ecology is so important.

A Problem Statement

These thoughts are prompted by a puzzle I have been considering for quite a while. Humans bestride the earth like a troubled colossus; on the one hand, we control more energy and material flows than any other species and on the other hand, these flows are slipping out of our control and threaten to end human life as we know it. Anthropocene and Anthropocide are joined at the hip, for it's our concern to make the world a better place for us to live that leads to collateral damage. So here’s the puzzle in a brief, stark version:

Why has human power gone hand in hand with human insignificance?

What do I mean by that? If you believe standard history, then the last six or seven hundred years have seen ever greater evidence of human insignificance. We were once God’s chosen species, to whom the earth was given as our domain, to go forth and multiply. The son of God was born human, not giraffe or whale and his sacrifice saved us all.

Human dominion was our birthright.

That birthright started being questioned a few hundred years ago, as the earth was toppled as the center of the universe, and subsequently, we discovered that we are nothing but a minor species in a minor planet in a minor star system in a minor galaxy. Perhaps in a minor universe as well. Darwin’s claim of evolutionary change was the final nail in the human coffin.

Meanwhile, another movement was taking place, one that multiplied human dominion to a scale unfathomable to the writers of the bible. Today, human dominion extends to the earth as a whole - we are in the anthropocene. Our lives are entangled with mechanical processes that extend our dominion to the Sky and the netherworld. We have never been more deeply enmeshed in the non-human world and we have never had as much power over it as we do today.

The contradiction: on the one hand lies the immensity of space, an utterly alien wasteland. On the other hand lies the kingdom of the earth that we rule with great violence. Which one is truly us?

If we have learned anything in the last five hundred years, it's that making humans the center of the universe is wrong in every sense of that term and yet we are stuck inside ourselves like brains in a vat.

Breaking free of our ‘species vat’ is the key task of normalizing ecology.

But how? We can take a clue from the famous slogan of Starship Enterprise: "to explore strange new worlds. To seek out new life and new civilizations. To boldly go where no one has gone before!"

We need to explore strange new worlds and to seek out new life. But there are no civilizations where we are going. Instead, we need to explore the alien landscape within ourselves and within the trillions of creatures that inhabit this planet. Our journey is as much a metaphysical one as it's a physical one, in which we will encounter selves that are like us in some ways but profoundly different in others. Who wouldn't want to be a blue whale for a day. Or an eagle? Or a tiger? What might it be like to be an Octopus? There are strange new worlds right where we live and our continued existence depends on our empathic understanding of these worlds.

However, our ecological empathy confronts an epistemic challenge right away: if our capacities are specifically human, then what knowledge can we ever acquire of the non-human?

Perhaps our capacities aren’t discontinuous with the rest of nature after all; that chimpanzees and bacteria are more like us than we are willing to accept. The counter to that argument is Nagel’s famous claim about what it’s like to be a bat: we will never know. In other words, we we increase our knowledge we are faced with new limits. Instead of dissipating, the contradiction gathers energy as it sails down the river of knowldege.

My claim is that the contradiction is really a dialectic, for each half of the dialectic contradicts the other only when contrasted as static oppositions rather than a spur for the other half, for it’s hard to tell where human ends and the rest of the universe begins. In the non-human world, robots, microbes and even rocks and stones have their own way of being, their own propensities, a world far removed from human agency and its desire to dominate the earth.

And then contradiction raises its head once again

Even as we move into the nonhuman world, we continue to use human categories to describe them, to believe that politics and power are the lens through which we describe the nonhuman world as well. If anything it’s the hyper-human, the human who straddles the earth like a god who confronts the non-human. Like Bohr confronting the quantum world, we are stuck with a problem: we believe that beyond the veil lies a world that’s frighteningly alien; yet, the only instruments we have at our disposal to understand this alien world is our all too human infrastructure. Further, all our successful attempts to transcend the barrier involve the creation of concepts and technologies that are - as far as we know - abstractions of the kind that only humans are capable of. There’s the romantic hope of the wilderness, an entirely non-human world untainted by human presence, but our hope for such a world confronts the reality of ever greater human control.

Wherever we look, there are only contradictions. What is to be done?

Some Readings

The list is long. Here’s a baker’s dozen to get us started:

Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet - edited by Tsing, Bubant et. al.

A Foray Into the Worlds of Animals and Humans - Jakob v Uexkull

The focus might be on ecology, but there’s only one biologist in the list - Uexkull, and he’s as much a shaman as a scientist (though Kimmerer is a trained biologist and many others in this list were trained as natural scientists). These are mostly works by philosophers, social scientists and humanities scholars for my goal is to foray into many worlds, the unknown unknown Earth. For this reason, I have deliberately omitted works by natural scientists writing as natural scientists.

Back in two weeks.