Normalizing the Planet 1

Planetary Politics

History with a capital H is 'Human' history, a condition of grace that’s only available to a special being, and even for them, it’s only a few super special beings who enjoy all its privileges. For a while that being was the second in command of God, but like Sauron taking over from Morgoth, they are now number one. A being that dominates the Earth and its creatures, whether it chooses to exploit them or hold them in its care.

The story was always the human story.

Did I hear you say ‘not every human.’ True, but…. while we were going forth and multiplying, it was easy to let the planet disappear into the background or neglect it altogether. Those days are gone, aren’t they? The carbon revolution has made sure the planet won’t be sidelined. Trotsky wanted us to live in a permanent communist revolution, but the liberation of the proletariat is a footnote to the liberation of carbon, which is the liberation theology that, until recently, united socialists, communists, capitalists, fascists and every other ‘ist. Industrial society is a revolutionary regime headed by the Carbon Liberation Front, aka the People’s Republic of Exxon, Aramco and Gazprom. The final and most complete human was baked in that revolution by the fires it unleashed.

We have to uncover the ontology of the human, but not in the classic sense of the fundamental categories of being but an empirically and historically grounded production of a new category (“human”) through processes that consume both energy and information.

The carbon revolution exacerbates every other tendency. We’ve never had so many people living together in such close proximity — with so much information and so little knowledge about others. This new reality will require us all to rethink our relationship with each other and the planet. I am talking about a much larger expansion of the concept of governance. We are entering an era of planetary politics, where the current obsessions of government such as taxes are going to be dethroned by the elemental obsessions of air, water, food, heat & climate. Summer in South Asia the past few years is a good example - when it’s so hot that you can’t think or work or do anything, you have a very different idea of what it is to order society.

Think: seven plagues, everywhere, all the time.

Normalizing the Human

The history of the world has seen many different forms of government, from monarchies to totalitarian states, from republics to military dictatorships. But not a single one of them said: let’s invite rivers to the house and oceans to the senate. Can you imagine? I don’t need to tell you that a politics in which oceans and glaciers get a vote will be radically different from our current one. Planetary politics will completely transform our idea of society in the light of the planet; in fact, we will need to rework the basic categories through which we experience the social — history, freedom, production and most importantly, the category human.

Some of us live in liberal democracies and others in authoritarian and semi-authoritarian regimes, but most of us live in societies that embrace human politics, i.e., a politics in which most humans who live within a territory are allowed to participate in principle, articulate their demands and in return have those needs be met by political institutions. It doesn't matter whether the justification for that politics is religious, communist or liberal - in all forms of human politics, we think the human and then ask how that space of humanity has to be ordered.

In all these territories, the human is normalized, i.e., it's taken for granted that the structures of everyday governance - from the post office to the school and the jail - have a background theory of the human and shape society on that basis. Every step you take from having breakfast to getting dressed and taking a bus to work and doing what your boss tells you to do is backstopped by a series of human spaces that we know how to inhabit, if only tacitly.

A planetary politics will have to make room for many other beings and create many new spaces for them. Climate change and the normalization of climate action both by political and economic actors is giving us a glimpse of what this normal state might look like.

The decisive next step is to think ‘planet’ just as we have managed to think ‘people’. We didn't think 'people' unaided, as a pure act of the mind; that thought was mediated - literally - by print and broadcast media, transportation technologies, market and trading arrangements, national and international institutions. These institutions didn't arise overnight, but the last three hundred years have seen a proliferation of capacities to think the human. Thinking the planet demands a similar expansion.

This planet is a new planet, not only ‘found’ as in nature, but also ‘made’, as in society.

What is Normalization?

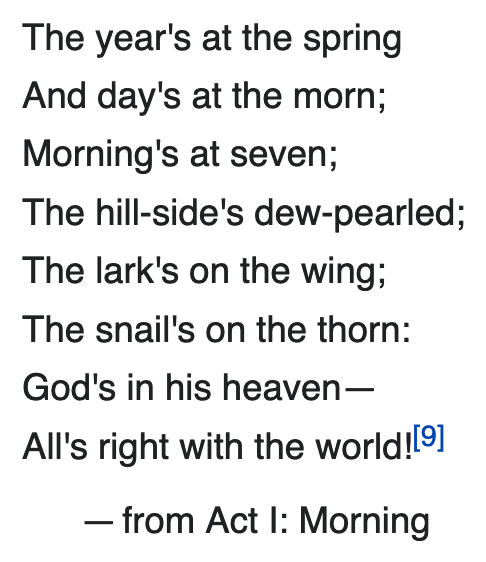

What is normal? There's no strict definition, for normal is somewhat in the eye of the beholder, but for our purposes, normal is that which runs on automatic. Automatic doesn't mean 'natural' for the automaticity is supported by any number of institutions, habits and rituals, but normal is that which is automatic given those background assumptions. Let’s say you’re living in a rural Christian community in the Southern United States. Going to Church on Sunday is normal while it takes some courage and resourcefulness to set that aside. In rural China it might be the opposite. I am reminded of this excerpt from Robert Browning’s ‘Pippa Passes’:

Normal is the default mode of everyday life, i.e., the places you inhabit, the processes you follow and the activities you perform because that's just the way things are done. Normal can be horrendously evil - like concentration camp guards smiling at picnics before going back to their jobs at the gas chamber - but the normal is banal. War can be normal, oppression can be normal, and gas guzzling can be normal, but in all these normals is the shared understanding that here's how the game is to played whether I am a winner or a loser.

In contrast, apocalypse is beyond the boundaries of the normal, like how the dinosaurs couldn't have done anything to prevent the asteroid from destroying their rule. But it’s possible to normalize the apocalypse as well, as we did during the Cold War. That’s why I find the work of Hermann Kahn fascinating; in his work on the Thermonuclear War, Kahn gave a sober (and therefore even more frightening) analysis of what it might take to win a nuclear war and survive its aftermath. We want to prevent nuclear meltdown and of course we want to prevent climate meltdown, but in order to do so, we have to bring the worst case scenario into our calculus and not have it be a post-Biblical end of all days which cannot be contemplated by humans.

If extinction is the modern counterpart of the day of judgment, then normalization is the secularization of extinction. We have secularized the apocalypse since 1945, with total extinction both a real possibility and the creation of institutions that will help us avoid the final countdown.

Similar to many other phenomena, normalization is not all or nothing: banal and catastrophic aren't the only two options. There's a graded transition from one to the other. For example, hybrid cars are an intermediate stage from the old normal of gas fueled vehicles to electric cars. Everything human is normal - agriculture and trade for sure, but also war and famine. We no longer think of any of those as divine grace or divine retribution. At the other end of the spectrum, if the Sun were to turn supernova tomorrow, we would be SOL. Climate change is tricky because it’s anthropogenic and yet, the fear is that it will unleash forces well outside our control, and our rhetoric reflects both worries - that we aren’t doing enough (anthropogenic climate action, so to speak) and that the earth will become uninhabitable if we let it go on. Apocalyptic thinking is a sign of radical uncertainty, that we are confronted with a Being that’s so completely Other that we cannot tell how it’s going to affect us. A good way to think about such beings that induce uncertainty is through Timothy Morton’s concept of the Hyperobject:

Hyperobjects are beyond our grasp:

I am not sure if Morton understands the concepts from physics and mathematics he has borrowed, but the basic idea is clear: a hyperobject is a being that occupies space and time at scales much bigger than the human and therefore can interact with us in unpredictable and even capricious ways. I will take at some length about Hyperobjects and their geometry in next week’s essay, but here’s the basic thesis:

Hyperobjects have a history, and beings can transition out of being hyperobjects.

For the planet to become normalized, it must cease to be a hyperobject.

Normalizing the Climate

When I first started thinking seriously about climate change - this was a couple of years before Greta, Extinction Rebellion, Sunrise and other popular movements - there were only two viable positions on climate. The first was: why aren't we doing a lot lot more? The second was: if we don't do a lot lot more, we are all going to die. Both were messages of despair, and I will be honest, I was and am fully convinced by both. Over the last few months, my despair has taken a turn for the 'normal' over the apocalyptic.

How so?

Like many in the despair camp, I nodded and raged while reading David Wallace-Wells’ spectacular piece of climate pornography. When I learned that it was the most shared article in the history of New York Magazine, it struck me that I am not the only person in the world thinking about planetary politics. Every hurricane, every fire and every drought increases the ranks of my fellow travelers. It’s only a matter of time when the oceans eating away our lands is part of everyday life, just as we listen to the weather forecast.

We aren’t used to inviting oceans into the senate but the survival of the human species depends on a politics that embraces the non-human world.

The term 'survival' is triggering, for it immediately makes us think of its opposite, i.e., extinction, which is an apocalyptic term. But here's another way of thinking about survival: that the institutions of state, market and civil society are in the business of promoting survival, for in their absence we will die in very large numbers. Failed states and war zones are exceptions to the rule, but we have normalized survival at a very large scale (7 billion and counting) and if it weren't for the fact that normalization is based on a fossil fuel regime that makes the entire structure unstable, we would not be talking about the climate crisis1. The economy is our current normal mode and even if it solves for survival poorly for many, it is a remarkably successful institution.

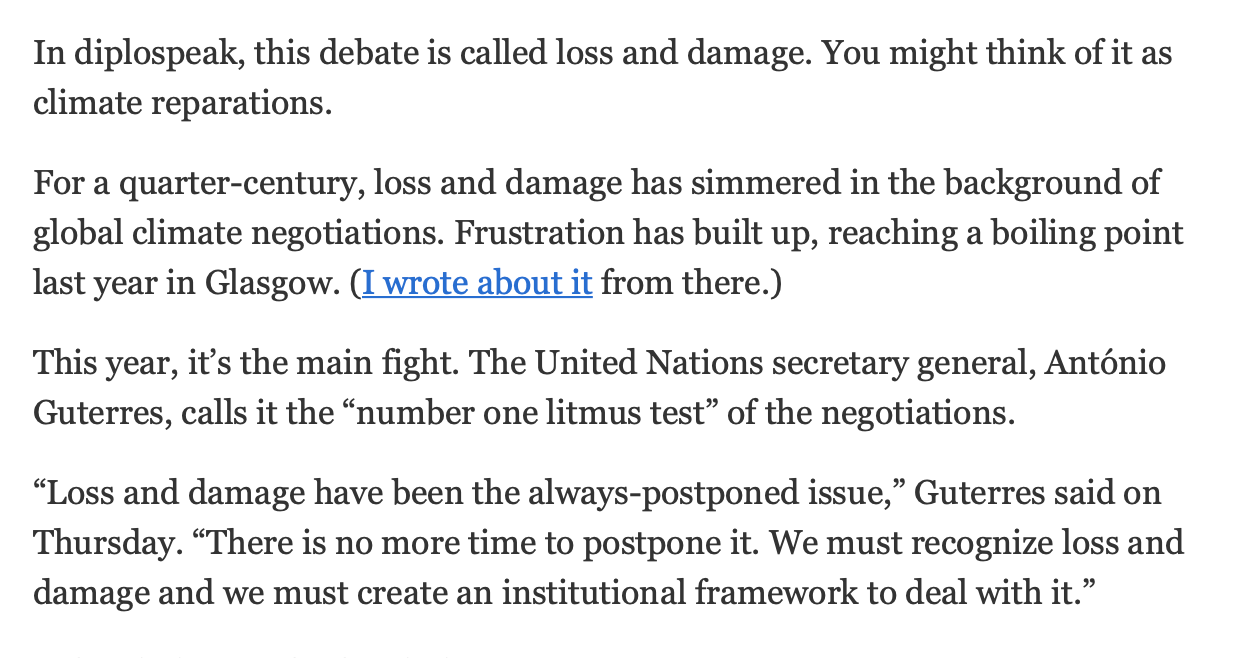

Evidence of survival talk in the climate context comes in the guise of 'Loss and Damage.' This year's COP puts L&D front and center.

Yes, it’s terrible injustice, but it’s no longer apocalyptic talk, and the fact the UN Secretary General is talking about reparations (without calling them so) is a sign the ‘why aren’t govts doing a lot lot more’ position is finding backing from normies. Another sign of normalization is talk about decarbonization, whether that means replacing gas powered vehicles with electric ones or directly removing carbon from the atmosphere. Solar is already the cheapest form of power in many parts of the world and it’s amazing how fast prices have dropped. Decarbonization takes the current normal as almost there, a good world which has exactly one flaw: fossil fuels. Replace the fossil fuel source with a renewable one and you’re done; Times Square can blaze all night long and more and more and more. It is, in fact, the updated American Dream…. and explains so much of the angst in the US climate movement - how can something that feels so American be rejected by so many people?

Perhaps the biggest sign of climate being normalized is that it’s being assimilated into a cascading series of crises, or a polycrisis as Adam Tooze calls it2.

Pandemic, drought, floods, mega storms and wildfires, threats of a third world war — how rapidly we have become inured to the list of shocks. So much so that, from time to time, it is worth standing back to consider the sheer strangeness of our situation. As former US Treasury secretary Lawrence Summers recently remarked: “This is the most complex, disparate and cross-cutting set of challenges that I can remember in the 40 years that I have been paying attention to such things.”

Normalizing the climate means that climate fully enters the arena of politics and economics - that it’s taken for granted that people across the world will initiate struggles to achieve their climate goals (and that the powerful will oppress them in response), that companies will try to make money on that account, that governments will go to war on climate disputes, i.e., anything we do today for oil we will do tomorrow for climate. From Tooze again:

A problem becomes a crisis when it challenges our ability to cope and thus threatens our identity. In the polycrisis the shocks are disparate, but they interact so that the whole is even more overwhelming than the sum of the parts. At times one feels as if one is losing one’s sense of reality. Is the mighty Mississippi really running dry and threatening to cut off the farms of the Midwest from the world economy? Did the January 6 riots really threaten the US Capitol? Are we really on the point of uncoupling the economies of the west from China? Things that would once have seemed fanciful are now facts.

Reading Tooze and Morton side by side, there’s plenty of similarity between Hyperobjects and Polycrises, but the Polycrisis overwhelms and challenges while a Hyperobject is simply ungraspable. You might say that in the history of normalization, we start with a Hyperobject but with effort, we can turn it into a Polycrisis. Everything from geoengineering to deep ecology will be seen as legitimate (if terrifying) pathways. In short: climate change will become part of the grammar of everyday life, infusing the pursuit of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness for everyone.

We would be talking about other crises, but not this specific one. Imagine if nuclear power had become dominant and plentiful and had powered a society full of electric cars and fast trains.

It’s been made famous by Tooze of late, but Polycrisis was coined at least as early as Edgar Morin’s Homeland Earth