This is the first of N (N ≧ 3) essays on the kind of AI I am interested in, and what we have to do to get there

Evolution and Revolution

AI is both evolutionary and revolutionary. Today's advances in AI are built upon developments in neural networks that are at least fifty years old. And these AI systems get their eyes and ears from the trillions of search queries and photographs and music uploads we have uploaded from our desktops and even more so, from our mobile devices. ChatGPT stands on the shoulders of Giant Robots. And if you can stand so tall that you can look over the fence surrounding your backyard, you can see the wide world outside. Quantitative shifts can precipitate revolutionary qualitative shifts. Let me mention two:

1. There's simplicity to the approaches that have worked: general purpose inference systems + reams of data + computing power. General-purpose systems have overtaken every specialized system. Of course, these systems are fragile and unable to grasp causality, but something feels right about the focus on general methods. Reminds me of physics: from the time when heliocentrism defeated epicycles, simple, symmetric theories have worked much better than complicated ones. But the simplicity of the new AI is different from the simplicity of physics and will offer philosophers and theorists much to chew upon. The principles aren't the same and we don't know what they are, so it’s blue sky right now.

2. It will put complex computation in the hands of non-technical users for the first time. For example, I can imagine a lot of white collar business communication being done by our AI assistants. Instead of mailing back and forth on when to meet and what to talk about when we meet, I might just say: "I need to talk to Ben about the six widget deal" and our respective AI assistants will a) figure out a time and b) set the agenda in advance.

Both evolutionary and revolutionary changes are on the way, but how can we prepare for the future without the hype and without being scammed? When I go to Medium’s AI home page right now, here’s what I see:

Slow Intelligence

I have deleted the author’s names in the screenshot from Medium, but the hype is unmistakable - stuff that will blow your mind, steal your job or seventeen new tools to try before tomorrow morning. With stock photos in tow. Not how I want to spend my day, either as a reader or as a writer. These articles are the informational equivalent of fast food: cheap and tasty but without much nutrition.

What’s the equivalent of slow food when it comes to understanding AI?

Even if AI continues to advance at a breathtaking pace, it won’t change our experience of the world overnight (unless it goes rogue and kills us all); primarily because we can’t change as quickly as the technology. We will grow into AI over a period of years (or decades), not months. The best way to grasp these new developments is to bite them one morsel at a time and digest them slowly.

That will take at least three to five years. No harm in trying a hack or two for short-term benefits, but the only way to internalize these techniques is by investing a substantial chunk of time.

I am not saying we should all invest 3-5 years learning how large language models work. There are other opportunities for us to ease into the post-AI world. Let me share one idea that’s definitely a growth opportunity.

The Biographer

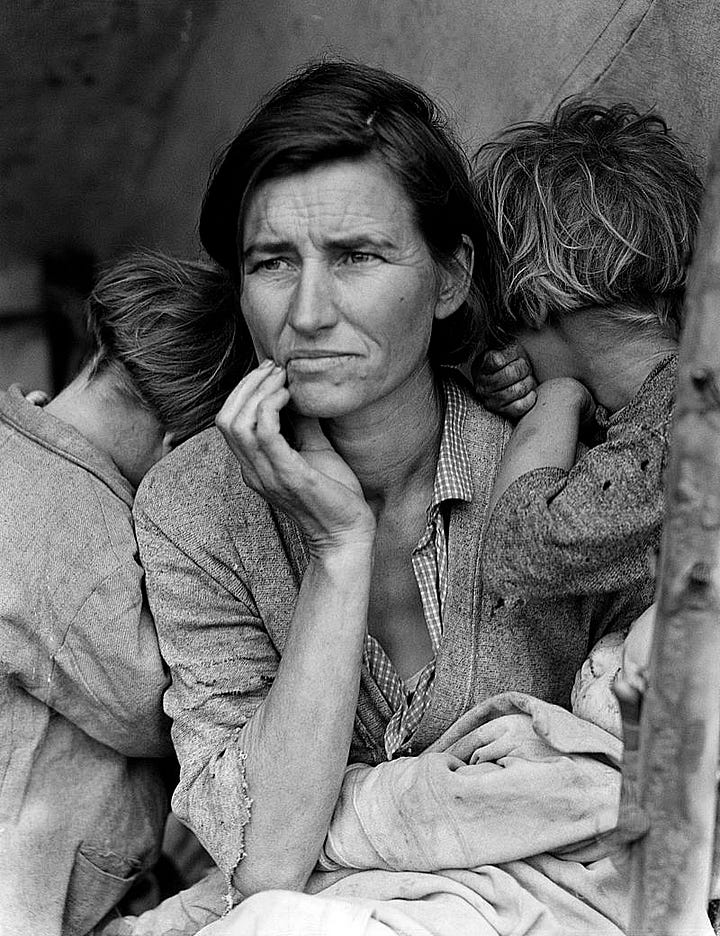

For much of history, portraits and statues were the preserve of the rich and famous. One of the innovations of modern painting was in the choice of subject - like Vermeer’s portraits of middle class Dutch folk such as the “Girl with the Pearl Earring” - the painting on the left. Photography made portraiture into a commodity, but for a long time it was a middle class profession with studios, photo-journalists and photo artists serving various demographics. That world is mostly gone with the proliferation of cameras in our pockets, but we didn’t have a camera when I was a child and the few photos there are of my childhood are from shots taken in studios. Photography was simultaneously a service, a craft and an art form (like the famous depression era photo on the right) that captured the human form in its various manifestations.

Not so much biography

To this day, we only read biographies of the rich, the famous and the powerful. It takes years for a biographer to sift through letters, facts and other records to grasp the facts of their subjects’ life. All that investment of time and effort has to pay off somehow; the life of the biographer’s subject has to be interesting enough to a wide audience, and for that reason, there isn’t a market for biographies of ordinary people. There isn’t a class of literary Vermeers who can turn their subject’s lives into art. Not yet. And not just the Vermeer level of portraiture; there isn’t the counterpart of the local photo studio either.

AI could change that situation

Most children born today will lead fully documented lives - photos taken almost everyday, updates on social media and messages sent to family members and so on. The life record is as complete for the average person as it used to be for a celebrity. That’s where the biographer comes in - their primary function is curatorial: work with the subject to figure out the important events in the subject’s life, collate pictures and videos, collect anecdotes and achievements and then fit those building blocks into a life template that the biographer has mastered. It could be a hero’s journey, a mildly ironic drama, a pastoral with the church community: a decent AI enabled biographer will take the raw material of our lives and turn it into a readable adventure. Audience: immediate friends and family, plus social media channels.

This doesn’t have to be expensive - $1000 could get a deluxe package in the US, and take about 10 hours of work including interviews, post-production etc, for a 30,000 word biography. AI would write most of the content with the template and the input data (life events, anecdotes etc) providing the skeleton. For extra money, I might get a yearly update. Of course, I could write the biography myself, using the same tools, but economies of scale matter here as much as anywhere else: if it takes me 50 hours instead of 10, I won’t have the stamina. Plus mastery over the templates and other stylistic elements, awareness of trending points of view and other fashions will take the novice biographer a couple of years to master, enough to dissuade everyone but the dedicated amateur, of whom there might be many. And who knows, out of this biographical craft might emerge a new artistic genre, the Vermeer who turns their ‘ordinary’ subject into an extraordinary biography.

I just made the ‘biographer’ up, but there will be new categories of products and services that AI will make possible - these aren’t high end goods for the wealthy, but affordable artifacts that attract a mass audience. Further, these new livelihoods won’t be dependent on having access to new, expensive AI models. I won’t be surprised if the computing infrastructure to run a biography studio will require no more than a laptop by the end of 2023.