How did we become the accumulative species: transitioning from property less roving bands to rivaling the Nitrogen production of the planet’s natural ecosystems? Broadly speaking there are two paths to answering this question: there’s the stuff of accumulation (cars and houses and OLED TVs) and there’s the stuff that helps you accumulate stuff (money). The second has always circulated more freely than the first, and in one of its forms was the medium of globalization.

If we agree the globe came into being somewhere between 1545 and the discovery of silver in Potosi and 1571 when the city of Manila was founded as a midway point for silver coming from the Americas to China, we are forced to ask a question: why did silver acquire so much prominence? Not just in China, which has historically been the largest market, but in a range of cultures spread across millennia. From a recent book:

Silver has been synonymous with wealth (along with its even more expensive cousin, gold) in most cultures. Trade in silver by land and by sea made globalization attractive: it was profitable enough that the Spanish conquerors worked indigenous communities to death in the silver mines and when that was no longer possible, profitable enough to import slaves from Africa.

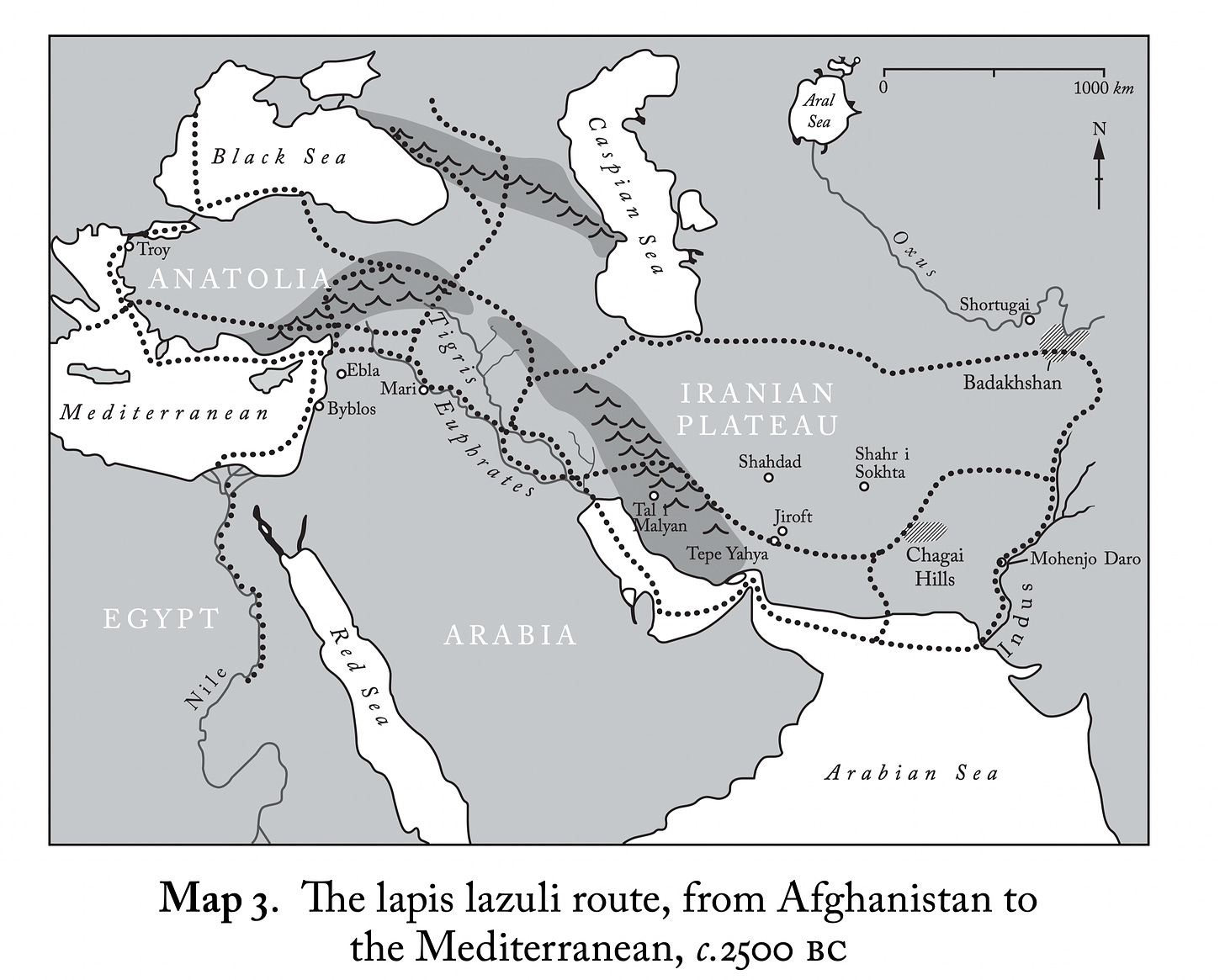

But silver wasn’t the first such commodity. The prize for the first substance that was widely prized and found its way thousands of miles from its source: Lapis Lazuli. The oldest Indus Valley site, Bhirrana, has Lapis Lazuli ornaments dating back to 7500 BCE.

The most important sources of Lapis Lazuli were in Afghanistan and Iran, but it’s most prominent use was in Egypt and Mesopotamia:

Was Lapis Lazuli money before silver? It certainly had widespread circulation:

I doubt that Lapis Lazuli was as universal a medium of exchange as silver seems to have been (but I could be wrong!) and it couldn’t have been a ledger of record or a pricing mechanism, but there’s another purpose to money that we seemed to have missed: a catalyst of flow. Think about it this way: let’s say you want to get into an exclusive club. You might show them the deed to your grand house on fifth avenue and write them a check for a million dollars for renovations. And then when you get in, you run a tab for which you pay in dollars once again. In other words, the dollar stands for two functions:

The code that gets you into the door.

The commodity that helps you complete transactions once you’re in.

But these two don’t have to be the same. Perhaps you got into the club because a prominent patron invited you in. Evidence of social capital doesn’t have to be evidence of financial capital. Lapis might have served more like a secret handshake and as a commodity desired by the elite, it may have also served as protection. You tell the guards you have Lapis for the pharaoh and they let you in. Once you’re in, you can show the rest of your wares. and then when you’re done in the palace, you can go out to the market and exchange so many kilos of wheat for so many heads of goat. Or proselytize your religious and philosophical convictions.

The point I am making is that commodity driven Eurasian integration seems to have a very long history starting in the Neolithic period, well before writing, empires, religions etc. Quite possibly, commodity circulation was the condition of possibility of all of these more ‘advanced’ features. How did early commodity circulation lead to unequal distribution of resources and the development of cities and empires?

I don’t have an answer to that question but others do.

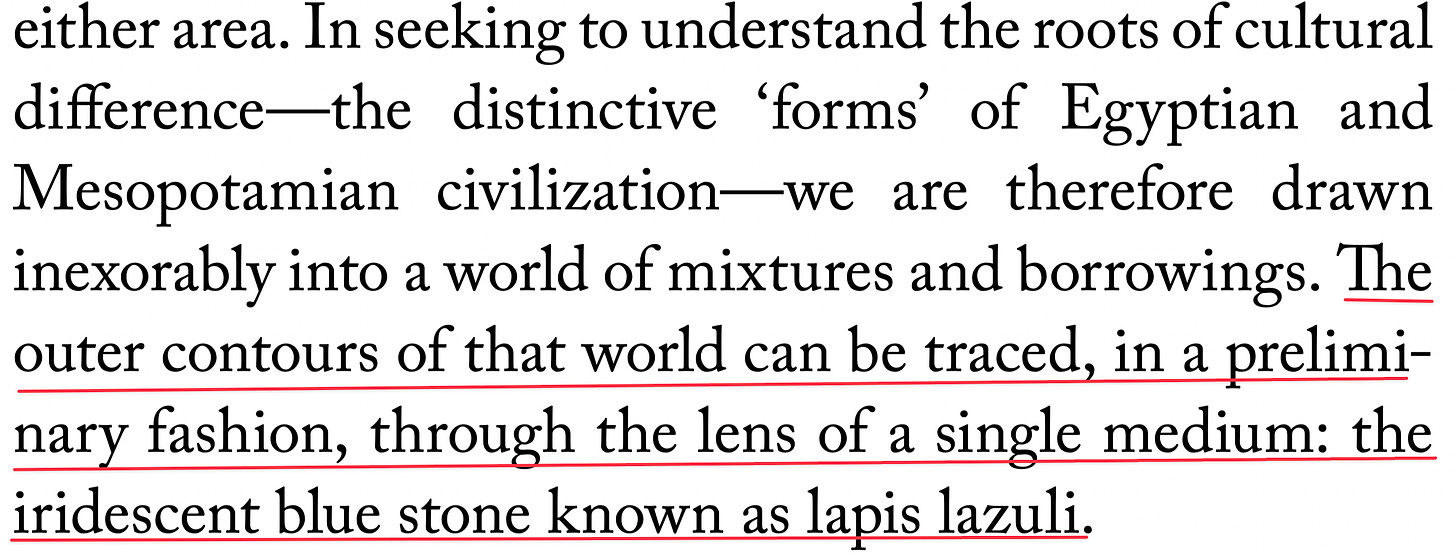

There’s also another intriguing question: given that all of these civilizations were importing some of their most crucial commodities from elsewhere, what gives them their unique civilizational form? Clash or not, what makes the Middle East the Middle East and what makes India, India?

One hypothesis: circulating commodities - Lapis, Silver, Information - have always produced both commonality and difference. What we now term ‘unique’ features of the various Eurasian civilizations aren’t there because they were bred in isolation but because they were bred in circulation.