The Book of Minds 4: Revolutionary Times

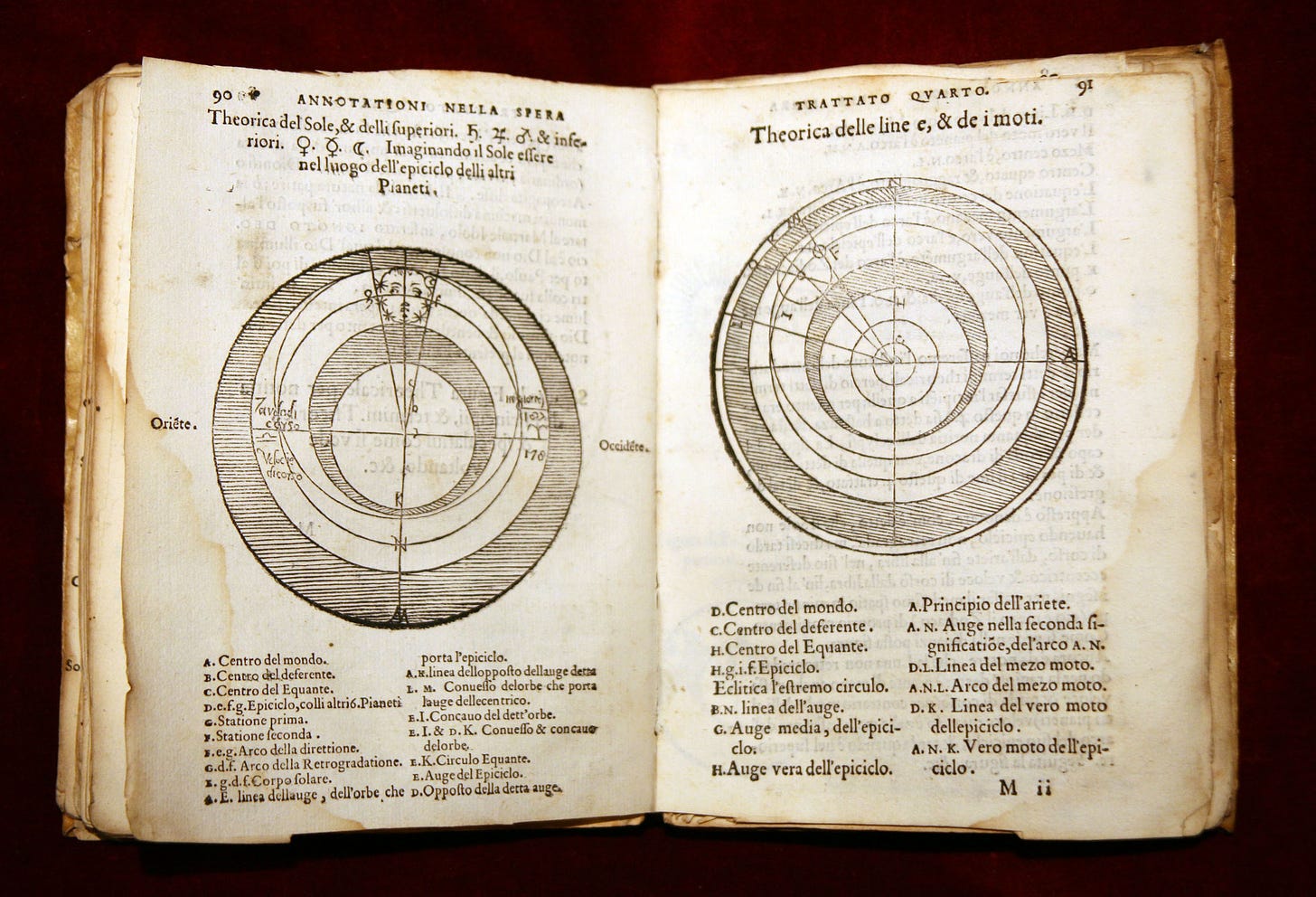

The Ptolemaic system of geocentric astronomy was in place by the early Christian era. We are so used to thinking about it as a medieval superstition that we don’t realize the magnitude of Ptolemy’s achievement: a mathematical model of planetary & solar motion that predicted the motion of all celestial objects against the fixed stars. Not bad at all. And it lasted almost 1500 years before it was replaced by the current Copernican model.

Could we be in a similar phase in the exploration of the mind - except that the anthropocentric phase lasted over two millennia? We have seen some fantastic insights into the nature of the mind from various philosophical and religious traditions, but they all take the human mind to be the paradigmatic mental entity.

That anthropocentric tradition was supercharged in the 1950s with the advent of AI and Cognitive Science, both of whom leveraged computation to model (in the case of Cognitive Science) and replicate (in the case of AI) the capacities of the human mind.

But what if the space of possible minds is much larger than the little niche occupied by humans?

If I were to think of a central premise of Ball’s book, it is this. And with any luck, since we live in a faster age, it won’t take 1500 years for us to set aside our anthropocentric ways. As I said a couple of essays before, our views of the mind oscillate between skepticism and speculation; while both have their usefulness, I would like to highlight a different principle: generosity, which says:

Let’s not prejudge what a mind must have for it to be a mind - while starting with the initial hypothesis that sentience, aboutness and subjectivity are central.

Let’s extend the possibility of mindedness (without knowing what that mean) to as many things as possible.

Generosity is the opposite of parochial, which assumes that having a mind is a uniquely human thing, or that the kind of mind humans have is the measure of all minds.

A subtler form of parochialism is the belief that other beings have minds, but we can’t access those minds because we are hobbled by the specifically human kind of mind we have, which comes from the belief that our minds are central to knowing the minds of other creatures.

How true is that assumption? Being made out of carbon and hydrogen and oxygen doesn’t prevent us from studying objects made out of silicon or uranium. Nevertheless It’s the challenge any first-person account of the mind has to overcome: is there a first person without a specific kind of first person?

One extreme version of specificity that seems like a genuine limitation (or is it?): I can only be me; I can’t be someone else. That clearly constrains my capacity to know the world, for I can only see what’s around me and not what’s a mile away. If my consciousness is constrained by my existence then:

What I can experience is constrained by my existence

I can know other minds only to the extent I can experience the world from their first person perspective

Your first personhood is accessible to me to the extent your existence is like mine.

If my bodily capacities are radically different from those of other species, then their minds will be inaccessible

Are there minds infinitely far away and forever unknowable?

If most minds are infinitely far away, we can’t grasp their world at all. Generosity bets on the opposite: that there are many minds and we can access them if we approach them the right way. To the extent the universe is full of minds, generosity is the way to go, and a science of the mind that parochializes the human is more likely to discover alien intelligences if and when they reveal themselves.