The Planet of Truth

With today’s article, I am back to writing weekday updates. That’s short essays M-F weaving three planetary threads:

Tagore & Gandhi and planetary thought.

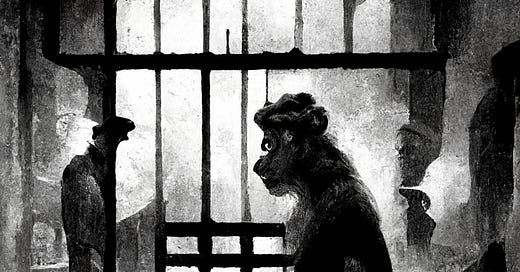

Animal minds and solidarity beyond the human.

The interverse and technologies of connection.

One of the great crimes of modern times is an epistemic crime: by the 60s, the fossil fuel companies knew (for they had commissioned the studies!) the potential impacts of carbon in the atmosphere, that it would lead to sea level rise and heat waves and other catastrophes. And instead of releasing their findings to the public, they spent decades denying the truth, preventing effective climate action at a time when it would have been much easier to do so.

I think about this crime a lot.

Science is real and yet all the scientists in the world haven’t been able to prevent Humpty Dumpty from falling off the wall. What gives? Of course, climate denial isn’t the only perversion of the truth; fake news is as much a deluge as sea level rise. There are many reasons why truth is under attack, but I also wonder: is our conception of the truth too brittle?

Accusations of flimsiness are common when it comes to evolution and climate change (standard bad faith attack: climate change/evolution is only a theory), but there’s an equally standard scientific response: innumerable studies under varied conditions continue to bolster the ‘theory’ that climate change and evolution are real.

However robust this theoretical conception of the truth might be - whether it’s the best explanation of the data or the most accurate correspondence with the state of the world - it doesn’t address the planetary question: how should we live our lives in the light of the planet? In fact, it’s very brittle in those circumstances, which was the real target of the fossil fuel corporations’ obfuscation: they don’t care if climate change is grasped akin to the Big Bang theory, i.e., as an abstract statement about some distant state of affairs. In contrast, they care very much about people switching away from gasoline.

Abstract truth is brittle in the face of lived reality and therefore, we need a ‘lived’ conception of the truth, the kind of truth people are willing to die for.

Historically, it’s religion that delivered truths worth dying for. The secular world had injustices but not untruths. Climate change is interesting in that truth is at the core of the struggle, and for that that truth to be a vehicle for justice and freedom, it has to be a public truth, not one locked away in journals and committees.

Public truths aren’t truths that are communicated to the public, but truths that are held by the public. The first is marketing, the second is ethics.

Tagore and Gandhi are interesting because more than a hundred years ago they saw that truth was essential to the anti-colonial struggle; freedom wasn’t merely a matter of kicking out the imperialist or establishing a nation state. Those are necessary but not sufficient conditions: the capitalist system responsible for colonization (and climate change today) has to be witnessed and known, but witnessing and knowing in the abstract sense aren’t enough: in the liberal system - the system that might yet produce the Climate Leviathan - witnessing and knowing are institutionalized in the form of massive datasets and climate models, international treaties, IPCC reports and Green New Deals. But the Leviathan is still a Leviathan.

Parts of the Western left recognize the dangers of any Leviathan, but its always good to step outside the hegemon for a different take. Tagore and Gandhi saw that the Leviathan itself needs to be questioned and the human freed from its clutches. Even more interestingly for a global audience: T&G were able to bring ideas and impulses from the Indian tradition to bear upon their aesthetic and political strategies.

We can take one step further: not just the human, the animal needs to be freed from the machine’s clutches.