The Virtues of Mindfulness

I have been thinking of meditation and mindfulness for many years; way back when, I was a grad student at MIT when the first international Mind and Life meeting brought the Dalai Lama in dialog with neuroscientists and launched the field that's now called contemplative neuroscience. A few years later in 2010, I was on the stage with the Dalai Lama at the MLI meeting in Delhi 👇🏾.

Those were heady days; I thought that we were finally about to combine insights from Indo-Tibetan philosophical and contemplative traditions, techniques from neuroscience and new technologies to create a better world. Or to paraphrase what I said in that video:

The day when Nagarjuna and Neuroscience are taught in the same breath is the day we have been waiting for.

Many thought that 'mindfulness' is the key concept that brings it all together. I have my misgivings as I outline below, but before we get to what's wrong, let's understand what the concept is taken to mean.

What is Mindfulness?

Mindfulness is a type of meditation in which you focus on being intensely aware of what you're sensing and feeling in the moment, without interpretation or judgment. Practicing mindfulness involves breathing methods, guided imagery, and other practices to relax the body and mind and help reduce stress.

Spending too much time planning, problem-solving, daydreaming, or thinking negative or random thoughts can be draining. It can also make you more likely to experience stress, anxiety and symptoms of depression. Practicing mindfulness exercises can help you direct your attention away from this kind of thinking and engage with the world around you.

Source: (mayoclinic.org)

I am deliberately quoting a mainstream source because I want to emphasize how widespread mindfulness has become and how its explicit and implicit values are shaping our view of mental health.

What's wrong with daydreaming? Why should it be brought under control?

The person most associated with the term mindfulness is Jon Kabat-Zinn, who left a career in molecular biology to study meditation and created a secular version of dhyana that's best known by its acronym MBSR - Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR). As a side-dish of gossip, the Zinn in Jon Kabat-Zinn comes from marrying into the family of the famous radical historian Howard Zinn. “Mindfulness is awareness that arises through paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment, non-judgementally,” says Kabat-Zinn. “And then I sometimes add, in the service of self-understanding and wisdom.” Nothing wrong with the initial impulse, but over time mindfulness has taken on a life beyond it's initial therapeutic role.

Mindful Appropriation

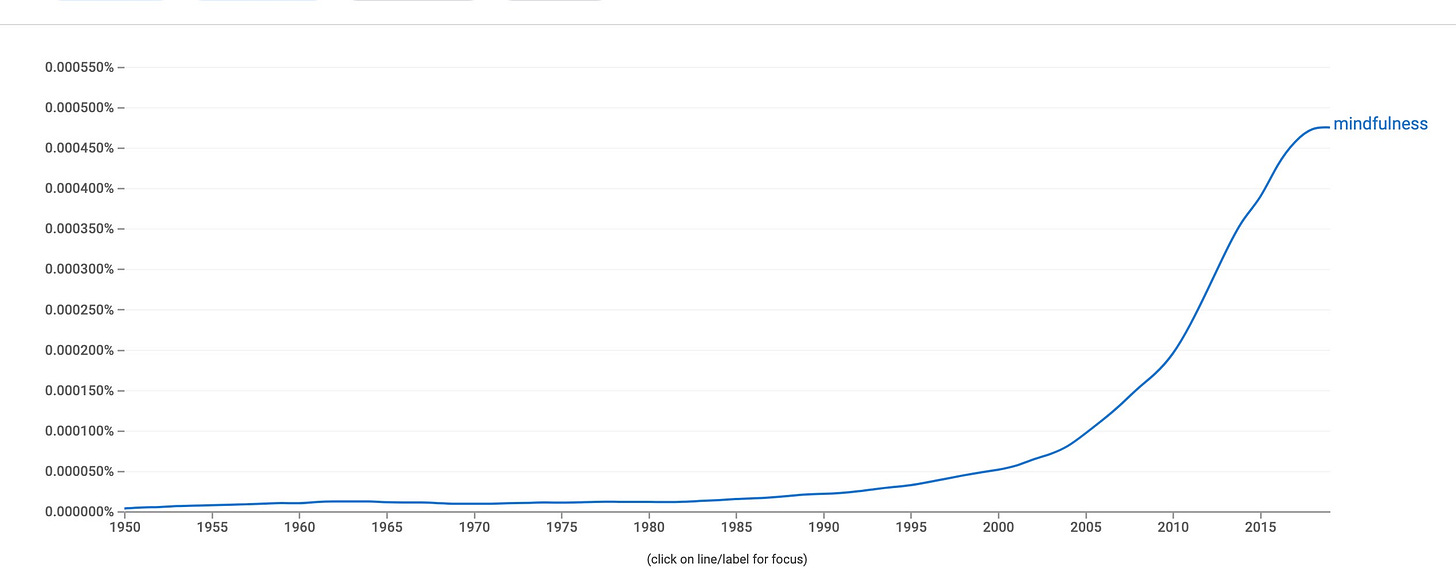

Nagarjuna hasn't become a meme yet, but like yoga before it, meditation as mindfulness has gone from being an 'eastern exocitism' to a white collar staple across the West, and in fact, it's that westernized practice that's coming back to India and other parts of the world. More Indians will practice mindfulness in its ‘Return of the Jedi’ form than ever practiced dhyana. Google's Ngram viewer gives a sense of the increasing popularity of the M-word.

Why not? In its avatar as MBSR, mindfulness has helped millions. Who am I to complain? But complain I did. I used to be very upset about cultural appropriation - not because there's anything wrong with turning a spiritual practice into a cure for stress, but because a sacred value has been completely transformed by market forces. There's good reason to complain when prominent figures in the mindfulness movement bend their minds towards the arc of capital. Instead, a core task of a contemplative view is to ask: why is it that the forces of modern society are turning people into anxious, lonely, stressed and angry individuals?

To reframe a Buddhist phrase as a question: what are the causes and conditions of loneliness?

On Loneliness

Hannah Arendt is known for her analysis of totalitarianism and of the collective derangement that leads to genocide. In her analysis of Adolf Eichmann trial, she coined the phrase ‘banality of evil,’ which expressed her puzzlement at the severe contrast between the mild-mannered and dull bureaucrat on the dock and the horrors that he perpetrated.

What prepares men for totalitarian domination in the non-totalitarian world is the fact that loneliness, once a borderline experience usually suffered in certain marginal social conditions like old age, has become an everyday experience …

– From The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) by Hannah Arendt

She was also unforgivably racist. As repulsive as her views of Africans and African Americans are, her analysis of totalitarianism is still worth reading. For example, her arguments about the relationship between totalitarianism and loneliness. Modern societies are individualistic, which means that both the abilities and the diseases of individuals are represented in full measure. In fact, the social construction of ability as well as illness are on display in the way we understand individualism.

Consider one of the great virtues of the modern world: solitude. Nothing is celebrated more than the genius artist or scientist who arrives at brilliant insights in the cave of their mind. More mundane, but equally prized, is the act of reading in private, of curling up with a book while consigning the rest of the universe to oblivion. Both virtues would be signs of psychopathology in other cultures and historical periods.

But solitude has its shadow, which is loneliness.

The lonely mind doesn’t have to be mistrustful or paranoid, but the condition of loneliness lends itself to both, especially if there are powerful forces that insert themselves into the widening gap between the lonely individual and others. I may be lonely and suffering and not even know why I am suffering, and while bowling alone, I am more than ready to listen to a great leader or a great party who says: you aren’t suffering because forces are tearing us apart, but because those outsiders, those bad people are coming for your jobs, for your community (of which you have none, by the way) and preventing you from the pursuit of happiness.

Lest you think loneliness is only a right-wing blue collar condition, it’s equally wide spread in the progressive white collar world as well, except that the remedies don’t involve making anyone great again. Instead, the focus is on marketized mindfulness, on searching inside oneself and using psychological and technological tools as a bridge. Meditation as optimization of attention with a high ROI. That marketized meditation has been severely and rightfully criticized by Ron Purser and others as McMindfulness.

Here’s the rub: neither MAGA nor marketized meditation will solve the problem of loneliness. The remedy to the crisis of alienation lies elsewhere. A hint lies in a third approach, which says the virtue we need isn’t solitude but solidarity, of working with others for better pay, better healthcare and a better environment. I am partial to solidarity — though, TBH, I love my solitude — but I can’t say with any surety that it will solve the problem of loneliness. I have a nagging doubt that it’s not up to the task either.

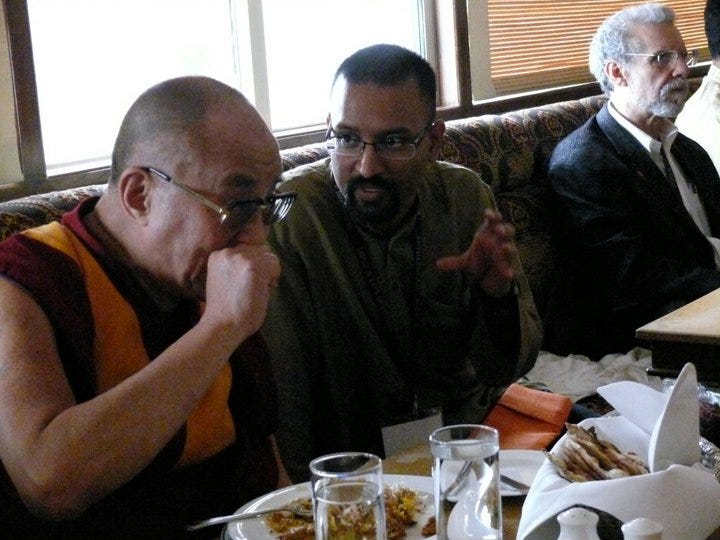

But between solitude & solidarity, there's a real possibility that contemplation in the broad sense of that term - meditation on one's own and meditation with others - is a promising way to address the problems of our times. What follows is a series of reflections on I would have liked to have unfolded in 2010, but had to wait a full decade. It was a project that began in this conversation 👇🏾 on the virtues of mindfulness - not as a way of becoming a more efficient worker or a more productive marketer, but as technologies for wisdom.

The proximate reason is a book review I am writing on the second volume in the 'Science and Philosophy in the Indian Buddhist Classics' series, which is on the Mind. The Dalai Lama's office reached out to me a few months ago to see if I could write a review; and the reflections you will be reading in the coming weeks came out of reading this book in depth, and reviving a range of dormant thoughts in the process. This note inaugurates a project that's part meditation manual, part philosophical and scientific exploration, part commentary on contemporary life. Quoting from the book I am reviewing:

As we have seen, Asaṅga’s model—the most dominant one for the Tibetan tradition—lays out the minimal set of omnipresent mental factors that must be present in any moment of consciousness, and he articulates a set of factors that must be present, at least in part, for more stable attentional states to occur.

In the long term, virtuous factors produce sukha—which can be translated as happiness, pleasure, or well-being—because they establish karma or mental conditioning that creates such results. In contrast, nonvirtuous states have the long-term effect of duḥkha—suffering, pain, or dissatisfactionbecause they establish the conditioning that leads to duḥkha.

But the key phrase comes a few paragraphs later:

Here again, we see the influence of concerns about contemplative practice in these accounts of mental factors. As noted above, Buddhist theories of spiritual transformation maintain that, while only wisdom can uproot the deepest causes of suffering and dissatisfaction, one must also train in meditative concentration, since the cultivation of wisdom requires that capacity. Likewise, the contemplative training in concentration will not succeed with a chaotic mind; one must also train in ethics—that is, one must cultivate virtue and reduce nonvirtue—precisely because mental afflictions, or nonvirtues, cause the mind to be unsettled in a way that inhibits the cultivation of attention.

In short, mindfulness (i.e., cultivation of certain mental factors) can't be divorced from wisdom and ethics. The question therefore arises: what's the wisdom of our times and what moral and material complexity does that wisdom need to engage? That's the question I want to address, and in doing so, I will operate in parallel on several registers:

A didactic register, explaining concepts as if I were writing a high school or undergraduate textbook,

An experimental register in which I will be prototyping new ideas and practices.

A polemic register which critiques the uses and abuses of mindfulness and contemplation more generally.

A scientific and technological register that looks at how cognitive neuroscience is revealing the neural and bodily correlates of contemplation and new technological tools that might make contemplation easier for most of us and reveal new forms of contemplative practice.

A literary register, which looks at the creative beauty of the classical tradition.

And so on.

Alright, let's end with a twist on a classical practice.

The 1% tax: a mindfulness technique with a twist

Here's a typical guided meditation:

One method is to sit in a straight-backed chair or sit cross-legged on the floor or a cushion, close one's eyes and bring attention to either the sensations of breathing in the proximity of one's nostrils or to the movements of the abdomen when breathing in and out.

In this meditation practice, one does not try to control one's breathing, but attempts to simply be aware of one's natural breathing process/rhythm.

When engaged in this practice, the mind will often run off to other thoughts and associations, and if this happens, one passively notices that the mind has wandered, and in an accepting, non-judgmental way, returns to focusing on breathing.

Now here's a modified version of this practice. I call it the 1% tax, i.e., should take about ten minutes of your day total.

Set an alarm for every two hours.

When the alarm rings, stop whatever you're doing (the obvious caveats apply - unless you're driving etc)

Write down the thought that was in your head immediately before the alarm rang.

Scan your body and notice what it's feeling like.

Sit down or stand up and bring your attention to the passing of breath on your nostrils for a minute.

Quit.

Try it for a few days and see what you notice about yourself!