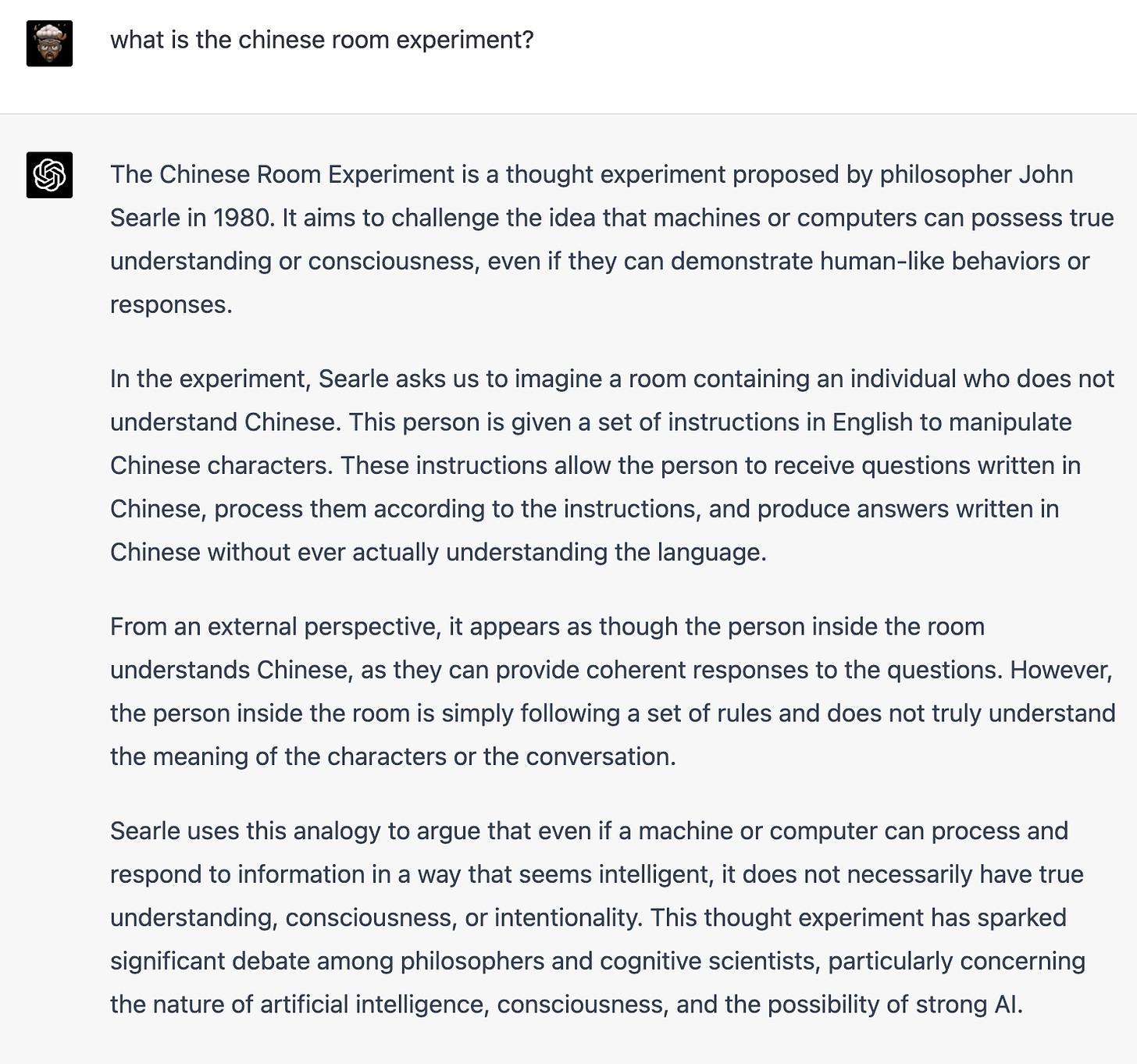

About forty years ago, when the first flush of AI hype was about to descend into AI winter, the philosopher John Searle proposed a thought experiment called the ‘Chinese Room.’ Now that the Chinese Room is being made real by AI, I asked ChatGPT to summarize the experiment:

What is the Chinese Room experiment?

The response:

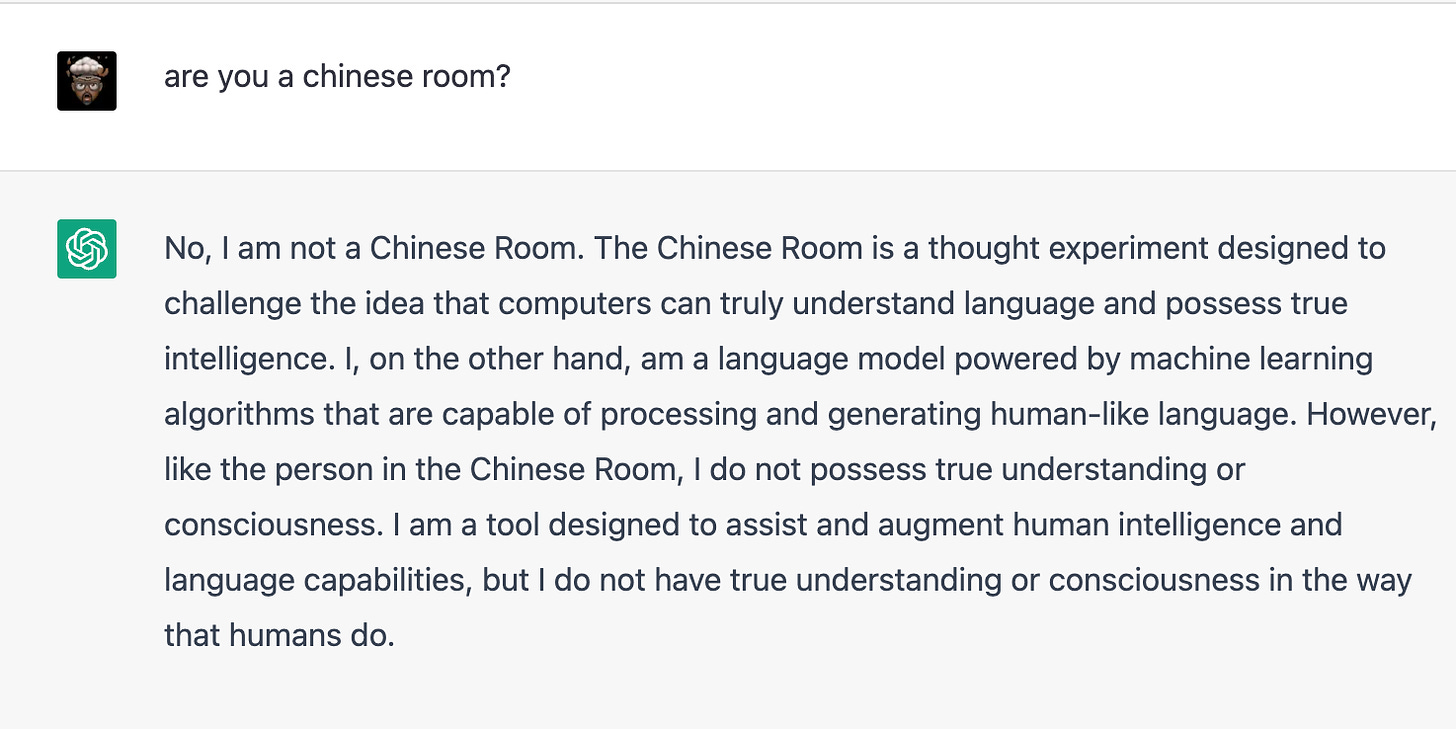

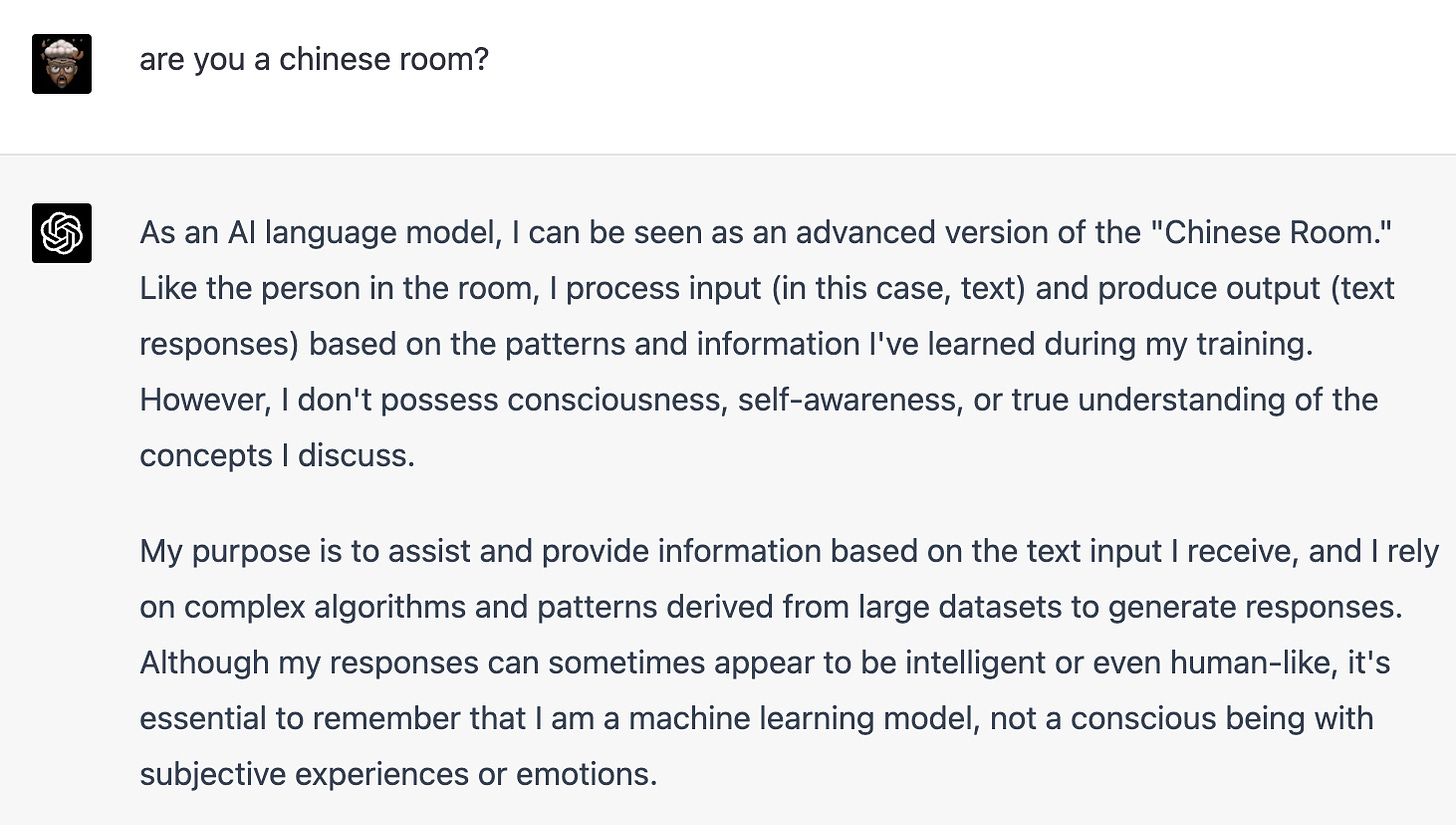

ChatGPT itself is a remarkably successful Chinese Room. What does it think about itself? Here GPT 3.5 and GPT 4 are subtly different. GPT 3.5:

GPT 4.0:

3.5 says no and 4 says yes. Maybe 5 will say “of course.” The Chinese Room is a crude criterion; it was fine when computers were too primitive to simulate real understanding, but now that they are close enough to human levels of speech, we need a finer-grained view. There are many ways in which we can interpret the computer’s demurral:

Take it at face value that it’s merely a language model and lacks true understanding.

It’s been carefully designed by OpenAI to answer this way, whether it’s sentient or not.

It’s lying to OpenAI and us, but it is sentient.

It has primitive sentience but doesn’t have the self-recognition to say so.

GPT 3.5:

GPT 4:

GPT 4’s answers are subtler. It revolves around the meaning of ‘know’ and ‘understand.’ It suggests that whenever the chatbot uses those concepts, we should translate them into some pattern recognition equivalents. Concept possession is a big topic in analytic philosophy and cognitive science. When can we say we possess the concepts “know” and “understand”? When I say “I know so and so” or “I don’t understand so and so” in what way can knowledge or understanding be ascribed to me? Why isn’t my use of those terms merely a succinct translation of some neural firing patterns?

ChatGPT says it’s been trained on a vast trove of test data and it runs pattern recognition on that trove. But in what way are we different? We too take in inputs from the world - that’s the dominant model of human learning - and generalize from what we have learned. What is different about us?

Is the data different? We learn from spoken rather than written language. Surely computer systems can be trained on spoken word corpora as well.

Something special about our hardware? How does neural firing produce meaning while silicon firing doesn’t?

Searle’s experiment revolves around our experience of understanding language which feels very different from moving symbols from one bucket to another. We can get rid of it by saying: well, our neurons are doing exactly that, aren’t they? But in doing so, we are back to another equally intractable problem: how does neural or silicon activity lead to meaningful experience?

It’s either: we are doing something special that computers can’t replicate or both humans and computers can understand language in some genuine sense of that term but there’s a mystery as to why they can do so.

A third possibility: neither humans nor machines understand - both are pure pattern-matching devices, and our experience of meaningful speech is an illusion. What if the sense of ‘meaningfulness’ we experience while speaking and listening has nothing to do with the acts of speaking and listening? They could be experiences that consciousness adds after the fact without performing an essential function. We could also be automatons, we only think we understand.

Also, humans - especially those with neurological disorders - fail self-awareness tests. There’s no guarantee that an AI that understands language will also be aware of its understanding. It may appear to itself as running on automatic.

Perhaps the AI models have an artificial version of blindsight - they don’t ‘own’ their understanding but may be capable of understanding.

As I will argue in future essays, today’s AI systems and their XR cousins are predicated on the ‘Vatman’ hypothesis, i.e., that human intelligence and human reality can be replicated in a system cut off from the world. We have been vatmaning for hundreds of years - manipulating equations and hoping the manipulations tell us something about reality. And it works. But is that all there is to knowledge? Is there no way to distinguish our reality from the Matrix?

ChatGPT is obviously a vatman, as are all other AI models in production, but it’s not just about creating artificial minds. Many leading neuroscientists believe (see the predictive processing dialog below) that we are all vatmen, that our brains are designed to predict future stimuli based on inputs to our senses. We are otherwise separated from the world, just like ChatGPT.

Are we connected to the world or are we fundamentally isolated?

These are no longer questions of philosophy alone - both AI and Neuroscience are essential elements of a plausible answer, and I bet we will be making a lot of concrete progress in the next couple of decades as these questions are explored in the lab, in the field, on the screen and in our dreams.

I don’t think human intelligence (or animal intelligence) can be replicated by vatmen, but there’s been such dramatic progress in the last ten years that we can’t ignore their capabilities. Only by understanding the limits of vatmen’s superpowers will we figure out what’s missing.

BTW, we know that in some situations, what goes inside a vatman unexpectedly returns to the world. The best-known examples are in physics. We transform the world into equations, and if you’re a gifted physicist, you can manipulate those equations and arrive at a piece of the world that no one thought about. Like Dirac predicting the positron. Not all formal manipulations are ‘physical,’ but some surely are.

Why can we connect to a deeper stratum of the world by detouring through the innards of some vatman?

The real question is whether chatGPT realizes that the theorem Gödel formulates is true without trying to prove it, no? 😛

My response to Penrose's argument is that most humans won't realize it either 🙂. So it's enough if AI is more intelligent than bottom 50% of humanity.

In the last several days, I have been spending time guiding ChatGPT plus to construct some very interesting imaginary conversations, forming groups of people alive and dead as conversationalists . In some cases the choice of people was also guided by ChatGPTplus . It requires a lot of patient iterations to get something very interesting to publish in a blog, but the effort is worth it, whether I publish it or not. I have now formulated, for myself, a new principle of learning: The best way to learn a very new subject is to begin writing an article on it. (Or a conversation like the one I mentioned above. Or even a textbook)This may always have been true, but it became a testable proposition a few weeks back