What is it like to be a Planet? Part I

Hard Science Fiction, if not Science Fiction as such, is the story of society’s victory over nature, so complete a victory that society has left the earth and wanders the universe. Like the start of Asimov’s Foundation series, where country —> city has been replaced by Galactic Rim —> Galactic Center.

In this grand story of civilization, aliens are estranged from us because they are technologically advanced, in Arthur C. Clarke’s famous maxim:

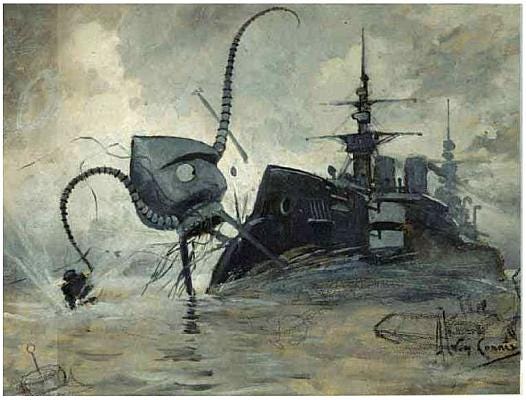

That’s when they are waaay more advanced than us, like the sentinel at the beginning of 2001: A Space Odyssey. If they are only a little bit more advanced, they can turn malevolent out of fear or cruelty, a story that’s been told again and again from the War of the Worlds to Independence Day to Remembrance of Earth’s Past. These are easier stories to tell, for both the human and the alien express emotions such as fear, greed, compassion and benevolence — familiar even when enacted at galactic scale. In fact, the universe itself is familiar, terra firma blown up to cosmic scale with galactic ambitions for size.

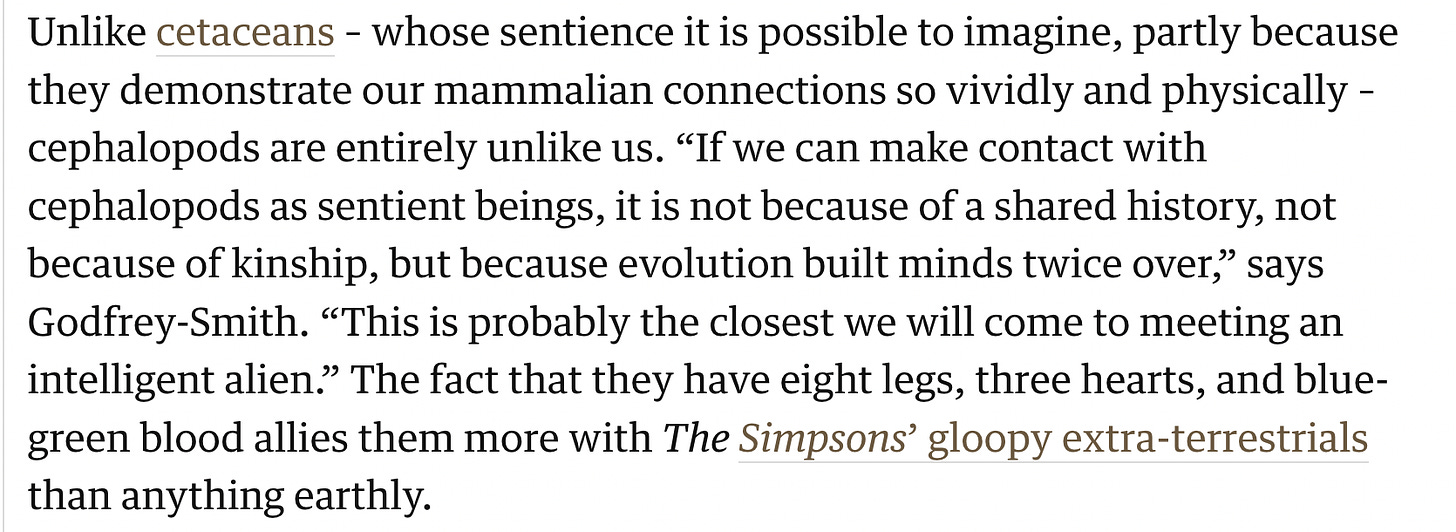

But there’s a very different perspective on what it is to be alien, which comes from looking at the history of life. There are aliens among us, creatures wildly different in their evolutionary history. The philosopher Peter Godfrey-Smith says it so:

Even octopuses are recognizably sentient. They hunt and hide as we would in the those circumstances. Some squirt water at people they don’t like. Others steal crabs from fisherman.

I am gonna go out on a limb and say that any mobile creature that’s between the sizes of a dime and a football field is understandable to us in essence, even if the details aren’t clear. It’s only when we relax one of those two constraints (or both) that we enter a truly alien world.

Plant intelligence — people say that term, but what do they mean? What is it like to be a rose? Or creatures that are much much smaller. Like what is it like to be a bacterium?

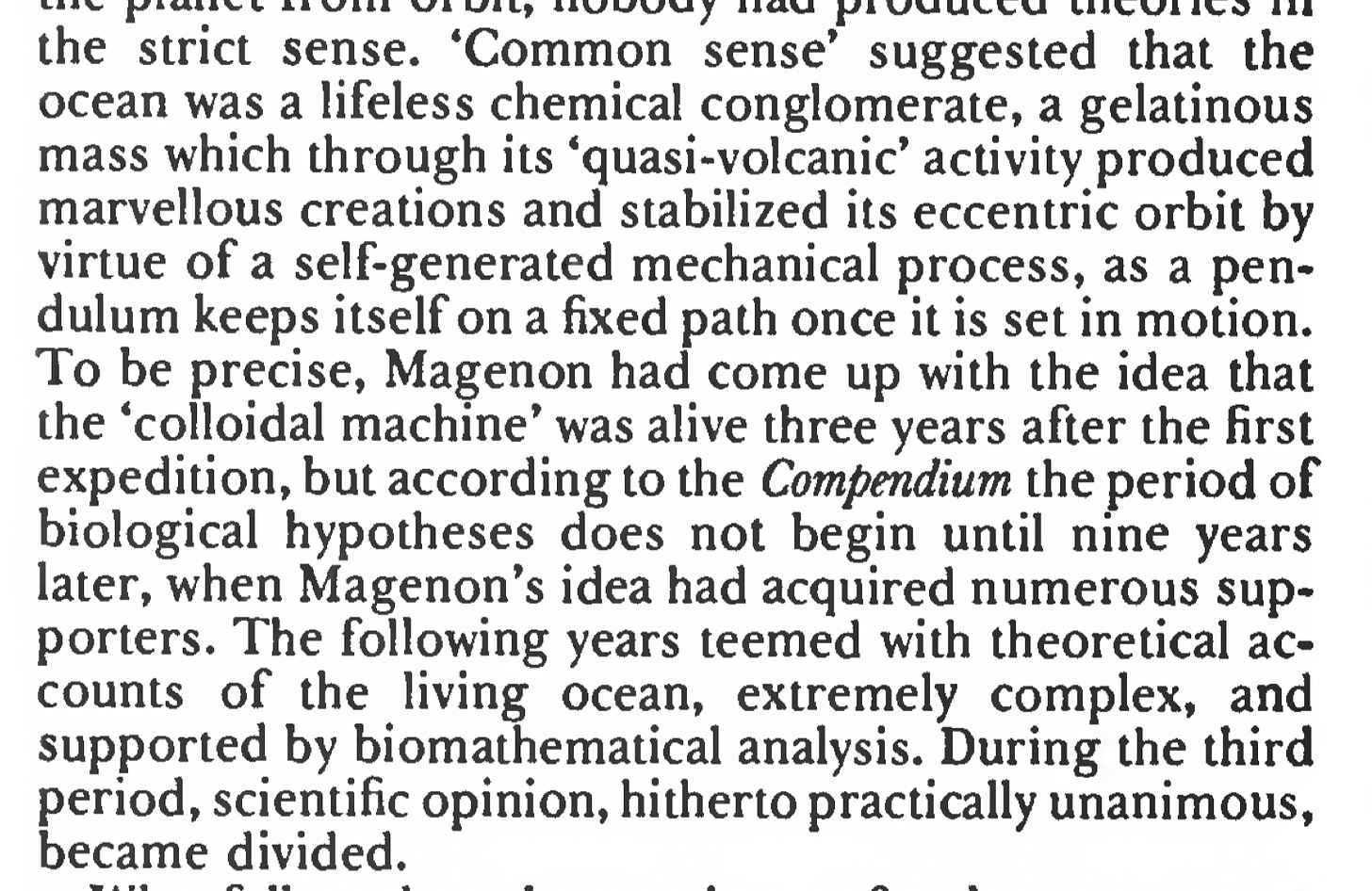

Solaris is distant from us in both dimensions. It’s internally dynamic, with ceaseless activity in its oceans and atmosphere, but it isn’t one entity in a medium that contains multitudes nearby. It’s also a millions of times bigger than us.

So how would be even experience this planet as a living, breathing creature? And what - if anything - can we make of its sentience? Is first contact with such an entity even possible? Two extremes:

We are no more capable of understanding a sentient planet than cats are capable of understanding quantum mechanics.

‘Humanness’ is infinitely expandable, it can leave its Homo-Sapiens casing and take on the POV of other creatures and stretched far enough, even inhabit the subjectivity of sentient planets.

Lem vacillates between these two extremes. He’s pretty convinced that we aren’t up to the task, that we are condemned to anthropomorphize a being that repels all anthropomorphism.

But he can’t shake the feeling that there’s something there for him. Perhaps not intellectual understanding, a theory of how Solaris works, but a visceral bond from one being to another.